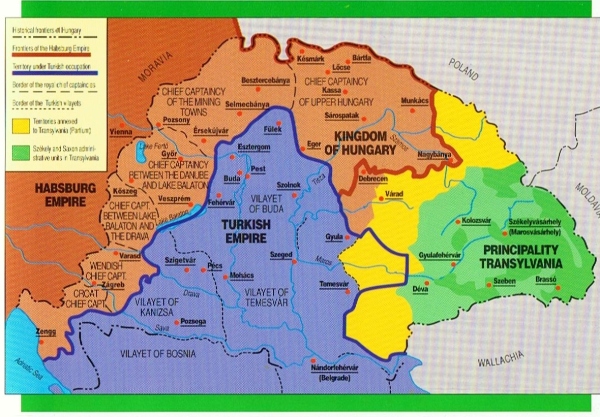

Following the catastrophic defeat of Louis II’s army at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, leading to the tripartite division of the Magyar lands for more than a century and a half, Hungarian contacts with the Britain were no longer episodic and accidental, but developed organically from Hungary’s internal situation. This situation developed in relation to Ottoman advances, the formation of an independent principality of Transylvania and the conversion of a large part of the Hungarian people to the Protestant faith. The connections with Britain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were mainly the outcome of these three great motifs in Hungarian political and intellectual life. British contacts with Hungarian Calvinism continued throughout the following centuries, continuing into the present one.

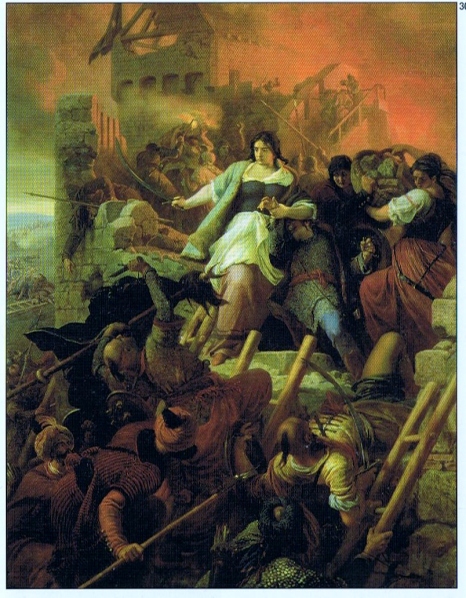

However, although King John Zápolya had sent an envoy to England after his coronation on 11 November, 1526, and there had been some contact between England and Transylvania, more official connections between the two countries came about only in the time of Queen Elizabeth I. Henry VIII had done little for the Hungarian cause despite Louis II’s request for help in 1526, perhaps partly due to King Ladislav’s harbouring of the last Plantagenet pretender, Richard de la Pole, during his father’s reign. However, his daughter Queen Elizabeth showed a greater appreciation of the threat to Christendom posed by the Ottoman occupation of a large part of the Hungarian territories. We know of some British noblemen who were in Hungary in 1566 and fought on the side of Nicholas Zrínyi in the defence of Szigetvár in the southern County of Baranya. Most notable among them was Sir Richard Grenville, who later took part in a famous attack upon the Spanish fleet. Queen Elizabeth tried to keep the Turkish peril constantly before the eyes of her subjects, partly in order to maintain national unity at a time of bitter continental conflict between Catholics and Protestants, which posed a threat to her position on the throne of England through almost constant internal plots and invasions from abroad. In 1566 she ordained that prayers should be said on three days of the week, including Sunday, for the whole country of Hungary, which has been the strongest bulwark of Christendom for a long time.

Below: Stephen Báthory (1571-1586)

English soldiers continued to crusade in Hungary against the Turks. Half of Europe was a battleground at that time, yet the love of adventure lured the English soldiers mostly to the war against the Turks. Several celebrated Englishmen travelled to Hungary, including Sir Philip Sidney, who sojourned there for a month in 1573. We do not know what places he visited, but we know that he spent a month in Hungary travelling without a guide, for which he was reproached in a letter from a friend. It seems likely that he was mostly interested in the political and military conditions of the country, for five years later a friend sent him a lengthy report of how Hungary could be defended against further Ottoman incursions. However, the English courtier and poet also made an interesting comment on the Hungarian custom of singing songs at banquets and other gatherings which dwelt on the bravery of ancestral heroes, songs which a soldiery nation believed were the best means to kindle valiant bravery into flame. The years 1571-3 were particularly rich in Hungarian literary products. In addition, Sydney emphasised the warlike spirit of Hungarian poetry. Otherwise, he reported only about the wars against the Turks and the devastation which they caused.

In 1579, however, there was a radical change in English diplomacy when William Harborne obtained a charter from the Sultan in Constantinople which secured for English merchants the same privileges as were enjoyed at that time by merchants of other states, particularly of Venice. A Turkish Company was founded and Anglo-Turkish diplomatic relations were put on a regulated basis. After that, political and commercial relations between England and the Ottoman Empire were generally friendly, and ‘the Sublime Porte’ often attributed great importance to the wishes of the English Court. It is entirely possible that the Polish chancellor called the attention of the Transylvanian politicians to the great influence of the English ambassador at Constantinople and to the feasibility of establishing contact with the English court through that embassy. This seemed all the more probable as Transylvania, having embraced Protestantism, could count on a certain sympathy in Elizabethan England.

Spiritual ties between Hungary and Britain had been called into being the puritan ideal common to both countries bridged the geographical gulf between them. Hungary’s contact with Great Britain as a whole became strongest in religious affairs, due to the maintenance of fraternal relations between the Calvinist (Reformed) Church in Hungary and their English and Scottish coreligionists, broadly known as Presbyterians by the seventeenth century, because they favoured the replacement of Bishops within the national churches of Scotland and England with a model of church government based on Calvin’s Geneva. In Hungary, interest was shown in Protestant England as far back as the middle of the century before, when Edward VI was on the throne. Hungarian theologians already felt compelled to go on a pilgrimage to England and its renowned cities. However, the first major theologian to have his visit recorded was Matthew Skaritza, who made the journey in 1571, according to Peter Bod. In contemporary Hungarian literature there is a long poem describing the martyr’s death of Thomas Cramner, written by Sztáray in 1582.

During the reign of Prince Sigismund Báthory (1586-1613), the Turkish-Polish peace was renegotiated, with the English ambassador at Constantinople, Edward Barton, demanding that Transylvania also be included in the peace agreement. What contemporaries thought about peace, may be seen from a note by Lestár Gyulaffy, secretary to the Prince of Transylvania:

Above all, the efforts of the Queen of England, who is held in very high esteem by the Turks, have greatly benefited both Transylvania and the Poles: next to God both nations can attribute their survival to her.

Two or three years later, when Transylvania was again faced with a threatening attitude from the Turks, Sigismund Báthory again sent an envoy, Stephen Kakas, to solicit the support of Queen Elizabeth. The Transylvanian envoy arrived at the Court in London at the beginning of 1594. Elizabeth I agreed to comply with all the requests made by the Prince of Transylvania, while in her Latin letter to him she bestowed special praise on the prudence and tact displayed by the envoy.

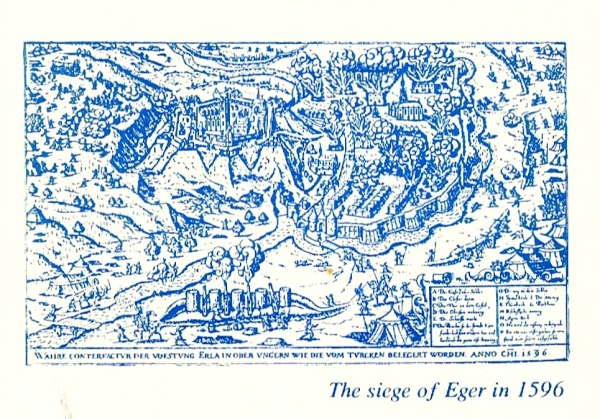

Lord Thomas Arundel distinguished himself in the siege of Esztergom of 1595, and Ben Johnson’s celebrated character, Captain Bobadill, boasted of his heroic deeds there in the comedy which was first performed in 1598. The siege of Eger in 1596 was witnessed by the diplomat Edward Burton, who described it in a dispatch to the Queen’s chief minister, Sir Robert Cecil on 5 January 1597. The earlier siege of the fortress town in 1552 had been watched with alarm in Western Europe, and there was general rejoicing when it was lifted. The first book in English about Hungary, Martin Fumée’s The Historie of the Troubles of Hungarie, was translated from the French original by in 1600 by ‘R. C. Gentleman’ (supposedly Rooke Church), and contains a colourful description of the siege. In the preface, the translator gave a frightful picture of Hungary’s devastation, which he had seen with his own eyes. He felt compassion for the once flourishing country and begged Sir Robert Cecil, to whom he dedicated the book, to assist the unfortunate country which doth now at last wander abroade, and is come to our little Iland… in ragged and mournful habits as a distressed Pilgrime to importune for her liberation from the Turkish yoke.

The preface expressed what its author perceived to be the view that contemporary Britain had of Hungary: the country was a great battlefield and the Hungarians defended themselves desperately against a powerful enemy. Whoever knew, wrote or told anything of Hungary at this time associated it with the fight against the Turks. This remained the case up until the beginning of the eighteenth century, when the Ottoman Empire’s power over the country was finally broken. The ambassador sent by Queen Bess to the Sublime Porte in 1596 passed through Transylvania and Hungary. The secretary wrote of impaled spies, uninhabited districts, destroyed towns and deserted ruins. When Richard Knolles had his book, The Turkish History, published in 1603, at the end of Elizabeth’s reign, he testified in his foreword to the strong sense of sympathy for Hungary in England at that time:

I was glad…to borrow the Knowledge of these late Affairs…also from the credible and certain Report, of some such Honorable minded Gentlemen of our own Country, as have either for their Honors’ sake served in the late wars in Hungary…

There was a valuable literature of pamphlets and broadsides about sieges and campaigns, so that the interest taken by English soldiers in the Hungarian-Turkish wars showed no signs of decline. Of course, the reality of daily life was somewhat different, as the Turkish occupiers were broadly far more tolerant of both Catholics and Protestants than the Hapsburg rulers who controlled a large part of the country, so that many Calvinist and Lutheran ‘refugees’ from the western side of the Danube found more fertile spiritual soil in the central lands controlled by the foreigners. This was also true of the Jewish Hungarians, who mostly settled east of the Danube, or in Transylvania, to avoid persecution under the Hapsburg tyranny which, at the time of the Counter-Reformation, was far worse for the Protestants than living under Ottoman rule.

Captain John Smith, of Jamestown and Pocohontas fame, was several times in Hungary before his adventures in the New World. His bravery there was what led to his promotion to the rank of captain, and he was alleged to have received a patent of nobility from Prince Sigismund Báthory. He claimed that, in Transylvania, he had fought duels with three Turks on three successive days before the walls of a Transylvanian town, cutting off the heads of all three while being watched from the battlements by beautiful ladies and brave warriors.

The indefatigable Scottish traveller, William Lithgow, visited Hungary in 1616. He was able to relate all kinds of interesting, hair-raising adventures from his sojourn. The taste of his reading public demanded adventurous, highly-coloured stories, and Lithgow never failed to satisfy the demand. He depicted with vivid colours a devastated Hungary, the prey of robbers and wild animals. At the same time, he showed not only the lamentable conditions prevailing in Hungary, but also the eagerness of the public to hear or read adventures from all those who returned to Britain from Hungary.

During the reign of Prince Gábor (Gabriel) Bethlen (1613-29), contacts between England and Transylvania increased. The activity of Thomas Roe, who had succeeded Edward Barton as English Ambassador in Constantinople, was particularly noteworthy at the time. The instructions of King James I to his ambassador at Constantinople was to prevent all attacks on Christian rulers. Roe considered Bethlen to be his friend, and contacts with Transylvania were so friendly and intense in those years that the English government even thought of establishing a permanent legation in Transylvania. Bethlen’s name was undoubtedly the best-known Hungarian name in early seventeenth century Britain. His policy of religious toleration was much admired by English public opinion, if not Scots. He was portrayed in contemporary English literature as well as later times: In Ben Johnson’s satirical play of 1625, Staple of News, one of the characters, ‘Lickfinger’ wishes to hear news of Gábor Bethlen, and is told, We hear he has discovered a drum to fill all Christendom with the sound. Byron gave the name ‘Gábor’ to the hero of one of his dramas, revealing the lasting legacy of the great statesman in England. A work by the Hungarian historian, Istvánfy, Historiarum De Rubris Ungaricus Libri XXXIV can be found in the Cathedral Library in Chichester. It details the life and actions of Gábor Bethlen and is in a valuable English binding with the arms of King James I on the cover. It is thought that it might have been brought or sent to England when there was a revival of interest in the history of Transylvania in Britain. Undoubtedly, Transylvania became a strong ally of the two kingdoms of James VI and I, possessing institutions, constitutional and religious liberties which excited the envy of the great nations of Western Europe.

Very interesting. Thank you for sharing. I never realized that John Smith went to Hungry or how close Transylvania was to that empire.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf and commented:

Hungary and its relations with Britain in Shakespeare’s time.