Forgotten England: Gentlemen Farmers and Labourers in the Agrarian and Industrial Revolutions

Part One: 1715 – 1815 – Agriculture, Trade and Towns.

In 1700, England and Wales were still largely agricultural countries. A total population of just five and a half million (the current population of Scotland) lived mostly in small villages and market towns. With a population of 674,000, London was the only sizeable town by modern standards. A medieval peasant transported from the year 1415 to the year 1715 would have found himself still in a familiar landscape. For most people in England at the beginning of the eighteenth century, life still centred around the village where they lived and worked. It was in this small circumference that the farm labourer spent the whole of his life. Villages were sited where the soil was suitable for growing crops or where sheep could be reared. The majority of the population lived, as in medieval times, in the south Midlands, East Anglia and the South East (see map), but even there, where the soil was most fertile, most villages had remained small.

In 1700, England and Wales were still largely agricultural countries. A total population of just five and a half million (the current population of Scotland) lived mostly in small villages and market towns. With a population of 674,000, London was the only sizeable town by modern standards. A medieval peasant transported from the year 1415 to the year 1715 would have found himself still in a familiar landscape. For most people in England at the beginning of the eighteenth century, life still centred around the village where they lived and worked. It was in this small circumference that the farm labourer spent the whole of his life. Villages were sited where the soil was suitable for growing crops or where sheep could be reared. The majority of the population lived, as in medieval times, in the south Midlands, East Anglia and the South East (see map), but even there, where the soil was most fertile, most villages had remained small.

A typical English farming village consisted of little more than a single street lined with farmhouses and cottages, surrounded on all sides by the fields worked by the villagers. At the centre were the manor house and the parish church. The lord of the manor, now known as the squire, continued to own more land than anybody else in the village, and was also the local magistrate or Justice of the Peace (JP), responsible for maintaining law and order. He might also be a Member of Parliament, which would increase his ability to help the people of the county borough he represented. Sometimes the squire might ride with the local hunt or go shooting, both of which sports were becoming increasingly popular. He would also entertain his friends and important neighbours to lavish meals. Squire Custance of Ringland in Norfolk frequently invited the local rector, Parson Woodforde, to dinner:

We had for dinner a Calf’s head, boiled fowl and tongue, a saddle of mutton roasted on the side table, and a swan roasted with currant jelly sauce for the first course. The second course a couple of wild fowl called dun fowls, larks, blamange, tarts, etc., etc. and a good dessert of fruit after among which was a damson cheese.

We had for dinner a Calf’s head, boiled fowl and tongue, a saddle of mutton roasted on the side table, and a swan roasted with currant jelly sauce for the first course. The second course a couple of wild fowl called dun fowls, larks, blamange, tarts, etc., etc. and a good dessert of fruit after among which was a damson cheese.

The rector was another important person in the village, and besides attending to his religious duties, he would supervise the farming of his land. As they had done for centuries, the tenant farmers provided the rector with a tenth, a tithe, of their produce. The tenant farmers rented their land, but other farmers owned theirs. The different holdings varied in size, but most consisted of less than forty hectares and many of less than ten hectares. Some villagers would work as labourers on the larger holdings. It was still common for these labourers to live in with the farmer and his family. Later, as farmers became more prosperous, this custom declined. The cottagers in the village might also work as labourers for part of the year. However, they mainly supported themselves by growing vegetables and a little corn on their small plots of land, or by grazing a few animals on the village common.

At the beginning of the century, perhaps half of the arable land in England still consisted of great open fields undivided by fences and hedges. In a village where this was so, farming would have changed little since medieval times. Very often the village had three big fields that were divided into strips of land separated only by uncultivated ridges known as balks. Each year one field was left fallow, with nothing being sown in it, a simple way of ensuring that the soil remained fertile. The open-field system worked well for centuries, but it did have its weaknesses. Since all the livestock in the village grazed together, disease could spread rapidly. One Oxfordshire farmer reported that he had known years when not a single sheep kept in open fields escaped the rot. In addition, some farmers’ lands were divided up into far too many lots, as many as twenty-four. Such inefficiencies did not matter so long as the land was producing enough food for both people and animals, but in the eighteenth century the population, recovering from the Great Plague in the century before, was increasing more rapidly than ever before. By the end of the century more than nine million people lived in England and Wales. To feed these people, the land had to be farmed more efficiently.

Life was precarious for labourers, cottagers and for the smaller farmers. They simply survived from one year to the next with nothing to put by as a surplus to support them in bad times or in their old age. Many families were compelled to seek help from the parish authorities because the man of the house had fallen sick. Rural poverty continued to be the largest single problem in England as the eighteenth century progressed. Only slightly above the growing number of unemployed and unemployable were the mass of those whose earnings were totally inadequate to keep body and soul together. Agricultural labourers were employed on a daily basis at five or six pence a day. In the slack seasons of the year, when the weather was bad and the harvests failed, they had nothing to do but stay at home or beg in the streets of nearby towns.

Life was precarious for labourers, cottagers and for the smaller farmers. They simply survived from one year to the next with nothing to put by as a surplus to support them in bad times or in their old age. Many families were compelled to seek help from the parish authorities because the man of the house had fallen sick. Rural poverty continued to be the largest single problem in England as the eighteenth century progressed. Only slightly above the growing number of unemployed and unemployable were the mass of those whose earnings were totally inadequate to keep body and soul together. Agricultural labourers were employed on a daily basis at five or six pence a day. In the slack seasons of the year, when the weather was bad and the harvests failed, they had nothing to do but stay at home or beg in the streets of nearby towns.

There had been a thriving woollen cloth industry since the fourteenth century, with its centre first in East Anglia and then in Yorkshire, based on the domestic system, with workshops and fulling mills, but factories were as yet unknown. Woollen cloth manufactured in England had been sold abroad for generations, with people working in their own homes. The yarn was spun and the cloth woven in cottages and farmhouses throughout the country. The West Country, East Anglia and Yorkshire were the three main centres of cloth production, where spinning and weaving had become full-time occupations for some, and a means of supplementing incomes for many more. Nevertheless, in Suffolk, even when the yarn industry was flourishing, employing about thirty-six thousand women and children, the spinsters were paid only three or four pence for a full day’s work and had to look to the parish for additional help.

There had been a thriving woollen cloth industry since the fourteenth century, with its centre first in East Anglia and then in Yorkshire, based on the domestic system, with workshops and fulling mills, but factories were as yet unknown. Woollen cloth manufactured in England had been sold abroad for generations, with people working in their own homes. The yarn was spun and the cloth woven in cottages and farmhouses throughout the country. The West Country, East Anglia and Yorkshire were the three main centres of cloth production, where spinning and weaving had become full-time occupations for some, and a means of supplementing incomes for many more. Nevertheless, in Suffolk, even when the yarn industry was flourishing, employing about thirty-six thousand women and children, the spinsters were paid only three or four pence for a full day’s work and had to look to the parish for additional help.

Though the poor rate increased in every community, the Elizabethan poor law was, by this time, quite inadequate to meet the needs of depressed rural communities. The system had to be supplemented by private acts of charity and many members of the more favoured classes considered such acts as part of their Christian social responsibility. Gentlemen, merchants, parsons and ladies founded almshouses, hospitals and schools. They left land and capital sums to provide for the perpetual relief of the poor.

Although these funds continue to assist rural communities today, at the time they were insufficient to fill the gap between needs and provision. By the mid-eighteenth century several parishes were seeking powers from Parliament for incorporating themselves and of regulating the employment and maintenance of the poor by certain rules not authorised by existing poor laws. Beginning in 1756, Acts were passed which gave parishes the authority to acquire funds for the building of houses of industry, bringing into existence the first workhouses.

There were, of course, many degrees and orders of society between the merchant and yeoman farmer and the artisan and casual labourer. In 1752 a carpenter could earn 1s. 10d. and a bricklayer (with mate) 3s 4d. for a day’s work. However, the insecure and short time nature of many rural occupations was clear for all to see and many to experience. Parents who wanted a greater degree of security for their children tried to place them in service. Any family aspiring to some sort of social status kept servants and could afford to do so because wages were so low. The servants accepted their pittance, long hours of work, lack of freedom and the insults of their betters because it would not have occurred to them to do otherwise and because they were reasonably fed, cleanly clothed and, by comparison with their own homes, luxuriously accommodated.

There were, of course, many degrees and orders of society between the merchant and yeoman farmer and the artisan and casual labourer. In 1752 a carpenter could earn 1s. 10d. and a bricklayer (with mate) 3s 4d. for a day’s work. However, the insecure and short time nature of many rural occupations was clear for all to see and many to experience. Parents who wanted a greater degree of security for their children tried to place them in service. Any family aspiring to some sort of social status kept servants and could afford to do so because wages were so low. The servants accepted their pittance, long hours of work, lack of freedom and the insults of their betters because it would not have occurred to them to do otherwise and because they were reasonably fed, cleanly clothed and, by comparison with their own homes, luxuriously accommodated.

However, the majority of Suffolk men and women continued to be employed in agriculture. Until the Agricultural Revolution of the second half of the century, the emphasis was still on animal husbandry. The dwindling demand for wool gradually reduced the sheep flocks, but Suffolk remained a prime supplier of mutton to the London markets, as well as of beef and poultry. Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) conjured up an intriguing picture of a turkey-drive:

An inhabitant of the place has counted three hundred droves pass in one season over Stratford Bridge on the River Stour; these droves contain from three hundred to one thousand in each drove, so one may suppose them to contain five hundred one within another, which is a hundred and fifty thousand in all.

An inhabitant of the place has counted three hundred droves pass in one season over Stratford Bridge on the River Stour; these droves contain from three hundred to one thousand in each drove, so one may suppose them to contain five hundred one within another, which is a hundred and fifty thousand in all.

Dairying was also important, with Suffolk cheese enjoying a reputation as impressive as that of the butter from the county, although Defoe himself did not like it. The butter produced in the county, as Kirby’s Suffolk Traveller affirmed in 1734, was justly esteemed the pleasantest and best in England. Most of the milk that went into Suffolk butter and cheese came from the old Suffolk dun cow. One reason why so much acreage was devoted to stock farming was that under the old rotation system, land had to be left fallow every third year. Suffolk farmers were the first to introduce a four-crop rotation in the mid-seventeenth century, so that by the beginning of the eighteenth century, many gentry and yeoman farmers were alternating turnips and clover with their wheat and barley. In other parts of the country such improvements were effected only on the estates of major landowners, but in Suffolk, writers on the subject observed that,

… the most interesting circumstance is… the rich yeomanry as they were once called being numerous, farmers occupying their own lands of value rising a hundred to four hundred pounds a year: a most valuable set of men who having the means and the most powerful inducements to good husbandry carry agriculture to a high degree of perfection.

When, in the latter half of the eighteenth century, the Agricultural Revolution began, at least the yeomen of Suffolk were prepared for it. The organisation of the woollen industry, on the other hand, varied greatly from place to place, though a general pattern can be traced. The man in charge in the domestic system was the clothier who arranged for the raw wool to be distributed or put out to the spinners to spin it into yarn, which would then be collected and put out once again to the weavers to make it into cloth. It took several spinsters to supply one weaver with sufficient yarn, so that clothiers were compelled to employ spinners from further and further afield. Daniel Defoe commented that,

… the weavers of Norwich and of the parts adjacent, and the weavers of Spitalfields in London… employ almost the whole counties of Cambridge, Bedford, and Hertford; and beside that, as if all this part of England were not sufficient for them they send a very great quantity of wool one hundred and fifty miles by land carriage to the north, as far as Westmorland, to be spun; and the yarn is brought back in the same manner to London and to Norwich.

In this way the clothiers employed hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of workers. Putters-out were employed to travel round distributing and collecting material, paying wages as they did so. They did not usually go to workers’ homes but would operate from depots set up throughout the area covered by the clothier. The workers would have to carry their material to and fro the barn, inn or shop, which served as their local depot. If foreign trade hit bad times the clothier would simply put out less wool, so that spinners and weavers would be thrown out of work, a cause of considerable complaint amongst them. For their part, the employers frequently complained of the delays caused by the custom of keeping ‘Saint Monday’ free for the alehouse.

In this way the clothiers employed hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of workers. Putters-out were employed to travel round distributing and collecting material, paying wages as they did so. They did not usually go to workers’ homes but would operate from depots set up throughout the area covered by the clothier. The workers would have to carry their material to and fro the barn, inn or shop, which served as their local depot. If foreign trade hit bad times the clothier would simply put out less wool, so that spinners and weavers would be thrown out of work, a cause of considerable complaint amongst them. For their part, the employers frequently complained of the delays caused by the custom of keeping ‘Saint Monday’ free for the alehouse.

The organisation of other textile industries, such as cotton and silk, was basically the same. However, the metal-manufacturing industry of the West Midlands and South Yorkshire were based more equally on the activities of both the men who supplied the metal and those who fashioned it into knives, swords, nails and similar products, in small sheds or workshops attached to their homes. Some industries, like coal mining and iron-smelting had to be conducted on a larger scale away from the home. Here and there, were hints of the factory system that was to develop.

In the textile industries some processes such as dyeing or fulling were already carried out in small mills because they required the operation of bulky water wheels and expensive equipment. In Yorkshire and throughout the Midlands, textiles were manufactured in clothiers’ homes, often in workshops and attics that were converted to let in as much light as possible. Defoe noticed this at Halifax:

… if we knocked at the door of any of the master manufacturers, we presently saw a house full of lusty fellows, some at the dye-vat, some dressing the cloths, some the loom, some one thing, some another, all hard at work, and full employed upon the manufacture…

As early as 1717 Sir Thomas Lombe had set up a silk mill at Derby, which housed three hundred workers Lombe’s building was greatly admired and became the pattern for the cotton factories when they were built, like the famous cotton mill that Richard Arkwright established at nearby Cromford in the 1760s. However, until the latter quarter of the eighteenth century, most industry remained based on the domestic system.

As early as 1717 Sir Thomas Lombe had set up a silk mill at Derby, which housed three hundred workers Lombe’s building was greatly admired and became the pattern for the cotton factories when they were built, like the famous cotton mill that Richard Arkwright established at nearby Cromford in the 1760s. However, until the latter quarter of the eighteenth century, most industry remained based on the domestic system.

The Industrial Revolution, in terms of a shift to factory-based production, passed East Anglia by. The growth of the manufacturing north confirmed an existing trend that had been underway since Tudor times. The roads and canals which linked the growing centres of industry in the North and Midlands with Oxford, London and Bristol sucked skill and commerce away from Suffolk’s textile towns and ports, and left a residuum of unemployment, depression and despair. Every town and village had its scenes of poverty and destitution. George Crabbe’s home town of Aldeburgh was no exception:

Between the roadway and the walls, offence

Invades all eyes and strikes on every sense:

There lie obscure at every open door

Heaps from the earth and sweepings from the floor,

And day by day the mingled masses grow,

As sinks are disembogued and kennels flow.

There hungry dogs from hungry children steal,

There pigs and chickens quarrel for a meal:

There dropsied infants wail without redress

And all is want and woe and wretchedness.

In this decayed port, warehouses, empty of merchandise, were let out as temporary havens to the homeless vagabonds. The magistrates, representatives of the gentry, wealthier farmers and more prosperous tradesmen, were increasingly concerned about the situation. They wanted to alleviate the suffering of the people beneath them.

The Agricultural Revolution took place during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when farmers had to produce more food to feed the growing population of England and Wales. They did this by improving the way they farmed and by cultivating more land. The most important change in this respect was the enclosure of the open fields, which in 1700 still accounted for something like half the arable land in England and Wales. When a village was enclosed each farmer’s land was consolidated into a single holding. This process had been going on for centuries, especially in East Anglia, but in the eighteenth century the enclosure movement accelerated rapidly throughout the whole of southern England and Wales. From 1760 to 1800 Parliament passed over a thousand Acts, and from 1800 to 1815 a further eight hundred. Contemporary reaction to such legislation varied, as did that of historians subsequently. A more detailed investigation of the evidence has revealed an important methodological principle, that it is difficult and dangerous to generalise on to a national scale from local evidence. The locality of agricultural experience determined the particular nature and impact of enclosure within it.

The Agricultural Revolution took place during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when farmers had to produce more food to feed the growing population of England and Wales. They did this by improving the way they farmed and by cultivating more land. The most important change in this respect was the enclosure of the open fields, which in 1700 still accounted for something like half the arable land in England and Wales. When a village was enclosed each farmer’s land was consolidated into a single holding. This process had been going on for centuries, especially in East Anglia, but in the eighteenth century the enclosure movement accelerated rapidly throughout the whole of southern England and Wales. From 1760 to 1800 Parliament passed over a thousand Acts, and from 1800 to 1815 a further eight hundred. Contemporary reaction to such legislation varied, as did that of historians subsequently. A more detailed investigation of the evidence has revealed an important methodological principle, that it is difficult and dangerous to generalise on to a national scale from local evidence. The locality of agricultural experience determined the particular nature and impact of enclosure within it.

Enclosures led to many improvements in farming. For example, they accelerated the spread of new farming methods. One of the most important was the development of new crop rotations to replace the traditional system whereby one field was left fallow each year. Farmers in Norfolk were among the first to discover that fallowing was unnecessary if proper use was made of crops like turnip and clover. These were fodder crops that enabled farmers to keep more livestock, and more animals meant more manure to enrich the soil. Due to this, and the fact that turnips, clover and other small crops enriched the soil, fallowing could be avoided if they were regularly alternated with grain crops. The Norfolk system, or variations of it, had been well established in East Anglia, the Home Counties and much of southern England by 1700. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the new rotations became increasingly popular.

Enclosures led to many improvements in farming. For example, they accelerated the spread of new farming methods. One of the most important was the development of new crop rotations to replace the traditional system whereby one field was left fallow each year. Farmers in Norfolk were among the first to discover that fallowing was unnecessary if proper use was made of crops like turnip and clover. These were fodder crops that enabled farmers to keep more livestock, and more animals meant more manure to enrich the soil. Due to this, and the fact that turnips, clover and other small crops enriched the soil, fallowing could be avoided if they were regularly alternated with grain crops. The Norfolk system, or variations of it, had been well established in East Anglia, the Home Counties and much of southern England by 1700. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the new rotations became increasingly popular.

Sophisticated systems of crop rotation, use of fertilisers, reclamation of waste land, regional specialisation, all these were marks of the new approach to farming. Since they kept more animals, farmers were also able to experiment with scientific, selective stockbreeding. Robert Bakewell was the most famous of a number of men who, by careful breeding, managed to produce much heavier livestock. They had shown not only that attention to diet – and, in particular, the use of root crops for winter feed – produced bigger, healthier animals, but also that it was possible, by in-breeding, to achieve in animals just those characteristics which are required. Suffolk gave the world three great breeds of domestic animals during this period – the Black Face sheep, the Red Poll cow and the Suffolk Punch, the most famous and best-loved of all the Suffolk shire horses. Thomas Crisp of Ufford owned the founding sire, from whom all these noble creatures descend, in the 1760s. In 1784 Sir John Cullum described the qualities of the breed in his History of Hawstead:

Sophisticated systems of crop rotation, use of fertilisers, reclamation of waste land, regional specialisation, all these were marks of the new approach to farming. Since they kept more animals, farmers were also able to experiment with scientific, selective stockbreeding. Robert Bakewell was the most famous of a number of men who, by careful breeding, managed to produce much heavier livestock. They had shown not only that attention to diet – and, in particular, the use of root crops for winter feed – produced bigger, healthier animals, but also that it was possible, by in-breeding, to achieve in animals just those characteristics which are required. Suffolk gave the world three great breeds of domestic animals during this period – the Black Face sheep, the Red Poll cow and the Suffolk Punch, the most famous and best-loved of all the Suffolk shire horses. Thomas Crisp of Ufford owned the founding sire, from whom all these noble creatures descend, in the 1760s. In 1784 Sir John Cullum described the qualities of the breed in his History of Hawstead:

They are not made to indulge the rapid impatience of this posting generation; but for draught, they are perhaps unrivalled, as for their gentle and tractable temper; and to exhibit proofs of their great power, drawing matches are sometimes made and the proprietors are as anxious for the success of their respective horses, as those can be whose racers aspire to the plates at Newmarket.

Wool was now of little importance to sheep farmers in Suffolk. What they needed were ewes that produced a large number of lambs, with a high meat quality. By the early 1800s it became clear that the best results were obtained by crossing Norfolk horned ewes, traditionally hardy animals, with Southdown rams, famed for their fattening qualities. The offspring were known at first as Blackfaces, but were eventually classified as a distinct breed, Suffolk Sheep. The Earl of Stradbroke was among the early enthusiastic champions of the breed and his famous shepherd Ishmael Cutter produced some remarkable results on the Earl’s pastures near Eye. In 1837 he raised 606 lambs from 413 ewes, a considerable achievement in the days before artificial feedstuffs.

Wool was now of little importance to sheep farmers in Suffolk. What they needed were ewes that produced a large number of lambs, with a high meat quality. By the early 1800s it became clear that the best results were obtained by crossing Norfolk horned ewes, traditionally hardy animals, with Southdown rams, famed for their fattening qualities. The offspring were known at first as Blackfaces, but were eventually classified as a distinct breed, Suffolk Sheep. The Earl of Stradbroke was among the early enthusiastic champions of the breed and his famous shepherd Ishmael Cutter produced some remarkable results on the Earl’s pastures near Eye. In 1837 he raised 606 lambs from 413 ewes, a considerable achievement in the days before artificial feedstuffs.

The great pioneering names in agriculture – Coke of Holkham (pictured left), Jethro Tull, and Robert Bakewell – belong to counties other than Suffolk, but that County’s claim to leadership in the Agrarian Revolution is undeniable. Early widespread interest in breeding, crop rotation, ploughing matches, and so on, led to the informal meetings of farmers to discuss their common problems. From this grew the nationwide organisation of Farmers’ Clubs in the early nineteenth century.

Suffolk also produced the man who more than any other may be called the evangelist of the Agrarian Revolution. Arthur Young was one of those who acted as a propagandist for this, publishing journals and books, and addressing meetings. Born in 1741, the son of the rector of Bradfield Combust, he inherited farmland in the parish and tried to work it, with disastrous results. He fared no better when he transferred his activities to Essex and Hertfordshire, but developed many ideas about farming from his experiences. In 1768 he published A Six Weeks’ Tour Through the southern Counties of England and Wales, the first of many books and pamphlets in which he surveyed the current state of agriculture in the regions. In 1784 he began a monthly journal, Annals of Agriculture, which covered every aspect of agriculture and ran for a quarter of a century. By 1793 he was recognised as one of the foremost authorities on farming and was appointed secretary to the newly formed Board of Agriculture. The following year, his General View of the County of Suffolk was published. Young gave wide publicity to every new agrarian idea, advocating enclosure, reclamation and the establishment of large farming units on which these latest ideas could be employed. He therefore helped to make farming a profession. It was this professionalism that enabled the awareness of the need for change among Suffolk farmers to take root. Edward Fitzgerald, the Woodbridge poet and eccentric, was certainly alive to the changes taking place:

The county about here, he wrote, is the cemetery of so many of my oldest friends; and the petty race of squires who have succeeded only use the earth for an investment… So I get to the water, where friends are not buried nor pathways stopped up.

Enclosure did not, however, automatically lead to improvement throughout either the county of Suffolk, nor the region and country more widely. Some soils were unsuitable for growing turnips and clover and some farmers were reluctant to change their ways. However, the enclosure movement gradually extended the area under cultivation. Between 1760 and the end of the century at least two million acres of wasteland were brought into cultivation in England and Wales. This, more than anything else explains why, during the period of the Industrial Revolution, England and Wales were able to support a much larger population without buying in large quantities of food from the continent. On the other hand, enclosure was an expensive investment. Landowners did not have to petition Parliament to pass an Act of Enclosure, but after 1750 most did, because they could not get agreement from the smaller farmers. The legal costs involved were high, and these were followed by the costs of fencing and building new roads.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century the Board of Agriculture estimated that the cost of enclosure by Act of Parliament was twenty-eight shillings per acre. Some of the smaller farmers could not pay this and had to sell up, but most survived, and found that, in time, the value of their land increased, enabling them to sell or mortgage part of it.

Nevertheless, encouraged by the government and directly patronised by George III (Farmer George), genteel farming became fashionable. Gentlemen farmers built themselves splendid new houses at the centres of their estates, and they went hunting and shooting together; the Duke of Grafton hunted with hounds from 1745 until the early nineteenth century, and the Suffolk hunt was established in 1823. The ladies played the harpsichord and the new pianoforte, paid each other visits, organised balls and made up theatre parties. The county’s major towns were revived as provincial centres of fashion, aping the customs of the capital. William Cobbett, writing in his Rural Rides, was so impressed by Bury St Edmunds (below), with its Assembly Rooms, newly opened Theatre Royal and Botanical Gardens, that he called it the nicest town in the world.

Nevertheless, encouraged by the government and directly patronised by George III (Farmer George), genteel farming became fashionable. Gentlemen farmers built themselves splendid new houses at the centres of their estates, and they went hunting and shooting together; the Duke of Grafton hunted with hounds from 1745 until the early nineteenth century, and the Suffolk hunt was established in 1823. The ladies played the harpsichord and the new pianoforte, paid each other visits, organised balls and made up theatre parties. The county’s major towns were revived as provincial centres of fashion, aping the customs of the capital. William Cobbett, writing in his Rural Rides, was so impressed by Bury St Edmunds (below), with its Assembly Rooms, newly opened Theatre Royal and Botanical Gardens, that he called it the nicest town in the world.

To sum up, the effects of enclosure were rarely great or immediate. In some instances enclosure came as the last act of a long-drawn-out drama of rural change. In other localities it sometimes introduced, but more often accelerated, a similar story of change. As the result of enclosure improved farming spread more rapidly than would otherwise have been the case, larger and more efficient farms were more readily developed, and the long-run decline of the smallholder and cottager hastened and made more certain. Enclosure provided a clear example of the large gains in economic efficiency and output which could be achieved by reorganisation of existing resources rather than by invention or new techniques. Enclosure meant more food for the growing population, more land under cultivation and, on balance, more employment in the countryside. Enclosed farms also provided a framework for the new advances of the nineteenth century. But in the pre-war period enclosure did not affect the whole country, and even the limited area that felt its influence was not transformed overnight.

To sum up, the effects of enclosure were rarely great or immediate. In some instances enclosure came as the last act of a long-drawn-out drama of rural change. In other localities it sometimes introduced, but more often accelerated, a similar story of change. As the result of enclosure improved farming spread more rapidly than would otherwise have been the case, larger and more efficient farms were more readily developed, and the long-run decline of the smallholder and cottager hastened and made more certain. Enclosure provided a clear example of the large gains in economic efficiency and output which could be achieved by reorganisation of existing resources rather than by invention or new techniques. Enclosure meant more food for the growing population, more land under cultivation and, on balance, more employment in the countryside. Enclosed farms also provided a framework for the new advances of the nineteenth century. But in the pre-war period enclosure did not affect the whole country, and even the limited area that felt its influence was not transformed overnight.

However, many poorer villagers felt the loss of the commons and wastes, and they were not given land in compensation. Coming at a time when the increasing population made it difficult for labourers to find work, many were forced to leave the land altogether to seek work in the expanding industrial towns and villages. In East Anglia, where industries were not developing, this forced them to seek help from the parish authorities. From the 1790s, however, the cost of outdoor relief, which did not require the recipient to enter a workhouse, began to shoot up because of the widespread distress caused by bad harvests, fluctuations in trade and the overpopulated countryside. The magistrates were most concerned to avoid a situation like that in France where a depressed peasantry had risen against their superiors in bloody revolution.

At the same time, they were also responsible for the provision of outdoor relief, and wanted to avoid encouraging the indolence of what they called, the undeserving poor, those whom they felt had no desire to work, as opposed to the deserving poor, whose poverty was due to no fault of their own. Their solution was the provision of workhouses, which soon became known, out of the hatred they engendered, as the Bastilles, but they did not provide a solution.

By the time Cobbett was writing in the 1820s, the language he was writing in had become fully standardised. Jonathan Swift’s Proposal for an English Academy may have been rejected early in the eighteenth century, but there were many who shared his frustration with the chaos in English spelling which threatened to make the gap between spoken and written English unbridgeable. In any increasingly classified and stratified society, it was no longer enough to rely on the aristocratic convention of spelling as you spoke, especially if you had not yet established your position in genteel society. More than ever, the educated Englishman and Englishwoman needed a dictionary. The rise of dictionaries is therefore associated with the rise of the English middle classes, keen to ape their betters and anxious to define and circumscribe the various worlds that they needed to conquer, lexical as well as social and commercial. It is therefore highly appropriate that Dr Samuel Johnson of Lichfield, the very model of an eighteenth-century literary man, published his Dictionary at the very beginning of the heyday of the making of the English middle classes.

Johnson was a poet and a critic who raised common sense to the heights of genius. His approach to the problems Swift had been worrying about was intensely practical and typically English. Rather than establish an Academy to settle arguments about language, he would write a dictionary, and would do it single-handedly. He signed the contract for the Dictionary with bookseller Robert Dodsley at Holborn in London in June 1746, setting up his dictionary workshop in a rented house in Gough Square. James Boswell, his biographer, described the garret where Johnson worked as fitted up like a counting house, with a long desk running down the middle at which the copying clerks could work standing up. Johnson himself was stationed on a rickety chair at an old crazy deal table, surrounded by a chaotic array of borrowed books. He was helped by six assistants, five of who were Scots and only one English, two of whom died in the preparation of the Dictionary.

It was an immense work, written in eighty large notebooks, containing more than forty thousand words, illustrating their many meanings with 114,000 quotations drawn from English writing on every subject, and from Elizabethan times onwards. It was not a completely original work, drawing on the best of all previous dictionaries to produce a synthesis, but unlike its predecessors, Johnson’s practical approach made it representative of English as a living language, reflecting its many shades of meaning. He adopted his definitions on the basis of English common law, according to precedent. After its publication, his dictionary was not seriously rivalled for over a century following its publication in April 1755. The fact that Johnson had done for the English Language in nine years what it had taken forty French academicians forty years to complete in French was the cause for much celebration. Johnson’s friend, pupil and Shakespearean actor, David Garrick, summed up the public mood:

It was an immense work, written in eighty large notebooks, containing more than forty thousand words, illustrating their many meanings with 114,000 quotations drawn from English writing on every subject, and from Elizabethan times onwards. It was not a completely original work, drawing on the best of all previous dictionaries to produce a synthesis, but unlike its predecessors, Johnson’s practical approach made it representative of English as a living language, reflecting its many shades of meaning. He adopted his definitions on the basis of English common law, according to precedent. After its publication, his dictionary was not seriously rivalled for over a century following its publication in April 1755. The fact that Johnson had done for the English Language in nine years what it had taken forty French academicians forty years to complete in French was the cause for much celebration. Johnson’s friend, pupil and Shakespearean actor, David Garrick, summed up the public mood:

And Johnson, well arm’d like a hero of yore,

Has beat forty French, and will beat forty more.

For all its faults and eccentricities, the two-volume work is a masterpiece and a landmark in the history of the language, the cornerstone of Standard English. In his Preface to the Dictionary, Johnson comments on Swift’s idea of fixing the language, scorning the idea of permanence in language. To believe in that was like believing in the elixir of eternal life, he said:

For all its faults and eccentricities, the two-volume work is a masterpiece and a landmark in the history of the language, the cornerstone of Standard English. In his Preface to the Dictionary, Johnson comments on Swift’s idea of fixing the language, scorning the idea of permanence in language. To believe in that was like believing in the elixir of eternal life, he said:

… may the lexicographer be derided, who being able to produce no example of a nation that has preserved their words and phrases from mutability, shall imagine that his dictionary can embalm his language, and secure from corruption and decay, that it is in his power to change… nature, and clear the world at once from folly, vanity and affectation… to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride, unwilling to measure its desires by its strength.

The Dictionary, together with his other writing, made Johnson famous, so that George III offered him a pension. James Boswell, a Scot, then made the great Englishman the stuff of legend and folklore. At the same time as Johnson was writing his tomes of correct English, the language of London, or at least of the working Londoner, based on the Anglo-Saxon dialects of Mercia, East Anglia and Kent, the English of Shakespeare’s Mistress Quickly, was being transformed into what we refer to today as Cockney.

The same economic forces that created a market for dictionaries and books of etiquette transformed the City into the square mile of money and trade that it is today. The old City dwellers of Pepys’ time, street traders, artisans and guild workers, were driven out, taking their distinctive accents with them to the docklands of Wapping and Shoreditch, and across the river to Bermondsey.

They were joined by refugees from the increasingly middle-class West End, as the new Georgian squares and terraces of Bloomsbury and Kensington displaced the working classes. At the same time, the combination of rural poverty and urban industry was depopulating the neighbouring countryside of Essex, Suffolk, Kent and Middlesex, bringing tens of thousands of destitute farm workers to the East End in search of work.

These country immigrants added their speech traditions to those of the London Language, what we refer to today as Cockney. In fact, the working-class speech of East London was originally a blend of oral traditions from the rural communities from which the majority of East Enders came as immigrants, keeping their traditions alive in the alehouses and wash-houses of Limehouse and Stratford East. Thomas Sheridan neatly described the situation of spoken English in London at the end of the eighteenth century:

Two different modes of pronunciation prevail, by which the inhabitants of one part of the town are distinguished from those of the other. One is current in the City, and is called the cockney; the other at the court end, and is called the polite pronunciation.

That polite pronunciation was much closer to the speech of the English middle classes. In the words of a contemporary lexicographer, Standard English was now based upon the general practice of men of letters and polite speakers in the Metropolis. One of the most distinctive changes was the widespread lengthening of the vowel in words like fast and path. The long a became, and has remained, one of the distinguishing features of south of England middle-class speech. However, at that time a cockney was simply a lower-class Londoner who spoke the language of the City. John Keats, the ostler’s son, was known as the Cockney poet because he came from London. The speech of East Enders may have been implicitly regarded as inferior, but it was not labelled Cockney in the way it is today. The old saying, born within the sound of Bow Bells by which Cockneys are supposedly defined, does not refer to the Bow of the East End, but to St Mary Le Bow, in Cheapside, in the heart of the City of London, some distance from what is now thought of as the East End. Traditionally, the East End starts at Aldgate, running along Commercial Road and Whitechapel Road as far as the River Lea, taking in Stepney, Limehouse, Bow, Old Ford, Whitechapel and Bethnal Green. The heart of Cockneyland is Poplar, and as well as being a locality, it is an attitude of mind. Stripped of all legends, Cockney therefore simply means East End working class. Thus, many of those who claim to have been born within the sound of Bow Bells have no claims to be cockney. The social reformer Henry Mayhew did not write about the East End and neither did he identify a special accent of dialect to the London Poor. It was the later Victorian reformers, following in his footsteps, who discovered what they called the East End.

That polite pronunciation was much closer to the speech of the English middle classes. In the words of a contemporary lexicographer, Standard English was now based upon the general practice of men of letters and polite speakers in the Metropolis. One of the most distinctive changes was the widespread lengthening of the vowel in words like fast and path. The long a became, and has remained, one of the distinguishing features of south of England middle-class speech. However, at that time a cockney was simply a lower-class Londoner who spoke the language of the City. John Keats, the ostler’s son, was known as the Cockney poet because he came from London. The speech of East Enders may have been implicitly regarded as inferior, but it was not labelled Cockney in the way it is today. The old saying, born within the sound of Bow Bells by which Cockneys are supposedly defined, does not refer to the Bow of the East End, but to St Mary Le Bow, in Cheapside, in the heart of the City of London, some distance from what is now thought of as the East End. Traditionally, the East End starts at Aldgate, running along Commercial Road and Whitechapel Road as far as the River Lea, taking in Stepney, Limehouse, Bow, Old Ford, Whitechapel and Bethnal Green. The heart of Cockneyland is Poplar, and as well as being a locality, it is an attitude of mind. Stripped of all legends, Cockney therefore simply means East End working class. Thus, many of those who claim to have been born within the sound of Bow Bells have no claims to be cockney. The social reformer Henry Mayhew did not write about the East End and neither did he identify a special accent of dialect to the London Poor. It was the later Victorian reformers, following in his footsteps, who discovered what they called the East End.

When the rural poor of East Anglia were crammed together in the East End many of the conditions in which the oral tradition of the countryside had flourished were intensified still further. There was no privacy; everything happened on the streets; they were isolated in a particular part of London, not least by the twists and turns of the Thames. Some aspects of the cockney way of life have continuity with the days of Charles II, before the Great Fire of 1666 and Wren’s rebuilding of the City. The market at Spitalfields, for example, still does a brisk trade every morning. Market gardeners and greengrocers trade in fruit and vegetables from the early hours of the morning, crying out as they have done for centuries. There is a whole class of speech characteristics that betray the rural roots of Cockney. For instance, it is very common to find the g missing in the participle –ing endings, contrasting with Midland English, as in eatin’ and drinkin’. This is not just the pronunciation of the labourers from eastern shires, but also that of their masters, for who it had become fashionable to go fishin’ and shootin’. This speech is incidentally and occasionally preserved for us in English literature of the period, as in that of Henry Fielding’s Squire Western and his heirs. Similarly, the Cockney pronunciation of gone, off and cough (gorn, orf, and corf) is still used by upper-class country speakers without a trace of class guilt. The characteristic long o, oo for ew, so it is no surprise that Cockneys say stoo for stew, nood for nude and noos for news, like most Americans. If the figures in Thomas Gainsborough’s paintings of Suffolk’s gentlemen farmers could speak, we might be surprised how similar some of their speech patterns might sound to those of East End barrow boys at Spitalfields.

When the rural poor of East Anglia were crammed together in the East End many of the conditions in which the oral tradition of the countryside had flourished were intensified still further. There was no privacy; everything happened on the streets; they were isolated in a particular part of London, not least by the twists and turns of the Thames. Some aspects of the cockney way of life have continuity with the days of Charles II, before the Great Fire of 1666 and Wren’s rebuilding of the City. The market at Spitalfields, for example, still does a brisk trade every morning. Market gardeners and greengrocers trade in fruit and vegetables from the early hours of the morning, crying out as they have done for centuries. There is a whole class of speech characteristics that betray the rural roots of Cockney. For instance, it is very common to find the g missing in the participle –ing endings, contrasting with Midland English, as in eatin’ and drinkin’. This is not just the pronunciation of the labourers from eastern shires, but also that of their masters, for who it had become fashionable to go fishin’ and shootin’. This speech is incidentally and occasionally preserved for us in English literature of the period, as in that of Henry Fielding’s Squire Western and his heirs. Similarly, the Cockney pronunciation of gone, off and cough (gorn, orf, and corf) is still used by upper-class country speakers without a trace of class guilt. The characteristic long o, oo for ew, so it is no surprise that Cockneys say stoo for stew, nood for nude and noos for news, like most Americans. If the figures in Thomas Gainsborough’s paintings of Suffolk’s gentlemen farmers could speak, we might be surprised how similar some of their speech patterns might sound to those of East End barrow boys at Spitalfields.

Given the obvious paucity of evidence regarding eighteenth century speech patterns, nothing could be more evocative of the people of the Suffolk countryside than the paintings Gainsborough. The great artist found fame and spent most of his life in London, but he learned his love of landscape in the countryside round his native Sudbury where, as a lad, he wandered the fields and lanes, sketchbook in hand. He moved to Ipswich in 1750 and soon found that while no one wanted to buy his landskips, the provincial elite clamoured for portraits that would immortalise their own concept of themselves – lords of their own little corners of creation. Gainsborough obliged, and grasped the opportunity to combine portraits with pictures of his own beloved Suffolk. His paintings were of idealised scenes of sunlit countryside, in which it was always summer, the corn was always ripe, the trees were always casting a delicious shade, and his sitters’ satin shoes never made contact with the rural mud.

Even Gainsborough’s peasants were figures of heroic simplicity for who life was a merry frolic in the warm harvest haystacks. For the men and women who could live in the heart of the rural community and yet be so shielded from reality as to indulge in such fantasies, life must have been good. Over many years large-scale farming in Suffolk paid well, especially cereal farming.

For the unemployed and under-employed landless labourers, life was far from good. From their point of view, however, war provided a better, if temporary, solution to the problem of the surplus population than the workhouse. From 1793 to 1815 England was almost continuously engaged in war with France in both its Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras. Men were pressed into the army and navy, some never to see their native fields again, others returning broken and useless, lifelong charges on the parish. The wars were hard on the coastal communities, with press gangs very active. No ships in the harbours could be manned until the navy’s requirements had been met, and even fishermen, usually exempt, were impressed into service. However, there were still not enough sailors for the ships of Nelson and Collingwood, and regular levies were made in the counties, Suffolk being told to raise three hundred men each year. Even towns as far inland as Banbury provided sailors; one of the Gullivers from that town apparently served on board Nelson’s HMS Victory.

In order to understand the importance of Britannia’s fight to rule the waves, we need first to understand how trade and industry had already been transformed during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Exports and imports had both increased dramatically, the chief export being textiles. In 1750, woollen cloth was still by far the most important textile made in Britain, chiefly from Yorkshire, but by the end of the century, as a result of the explosive growth of the Lancashire textile industry, the export of cotton goods almost equalled that of woollens. Whereas the greater part of Britain’s trade was with the continent in 1700, by a century later it had changed direction completely. More and more dealings were with the West Indies and North America, which grew at a spectacular rate. This brought prosperity to the western coastal ports of Whitehaven, Liverpool and Bristol (right), which were better placed than those of London, East Anglia and the south coast for the trans-Atlantic trade. Liverpools’s population increased from around six thousand in 1700 to over eighty thousand by 1800. Much of this increased prosperity was based on the slave trade. Slaves sold in the West Indies for roughly five times what they had cost on the African coast, and the ships were then filled with sugar, rum or tobacco, and increasingly with cotton, to complete the third side of the triangular trade.

In order to understand the importance of Britannia’s fight to rule the waves, we need first to understand how trade and industry had already been transformed during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Exports and imports had both increased dramatically, the chief export being textiles. In 1750, woollen cloth was still by far the most important textile made in Britain, chiefly from Yorkshire, but by the end of the century, as a result of the explosive growth of the Lancashire textile industry, the export of cotton goods almost equalled that of woollens. Whereas the greater part of Britain’s trade was with the continent in 1700, by a century later it had changed direction completely. More and more dealings were with the West Indies and North America, which grew at a spectacular rate. This brought prosperity to the western coastal ports of Whitehaven, Liverpool and Bristol (right), which were better placed than those of London, East Anglia and the south coast for the trans-Atlantic trade. Liverpools’s population increased from around six thousand in 1700 to over eighty thousand by 1800. Much of this increased prosperity was based on the slave trade. Slaves sold in the West Indies for roughly five times what they had cost on the African coast, and the ships were then filled with sugar, rum or tobacco, and increasingly with cotton, to complete the third side of the triangular trade.

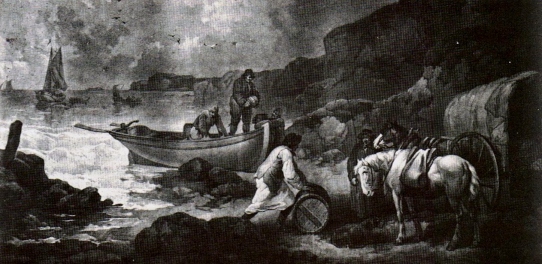

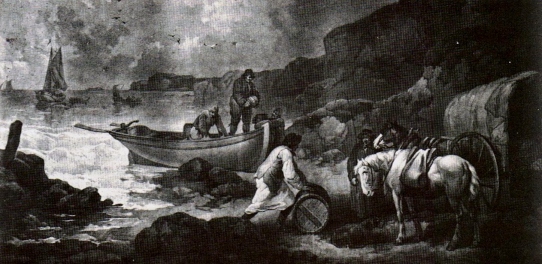

For the time being, however, it was groceries such as sugar, spices and tea, which formed the largest group of imports. The most English of pastimes, tea drinking, achieved wide popularity during the course of the century, though an excessively high import duty meant that about two-thirds of that consumed was brought in by smugglers such as Richard Andrews, who supplied Parson Woodforde among many others:

For the time being, however, it was groceries such as sugar, spices and tea, which formed the largest group of imports. The most English of pastimes, tea drinking, achieved wide popularity during the course of the century, though an excessively high import duty meant that about two-thirds of that consumed was brought in by smugglers such as Richard Andrews, who supplied Parson Woodforde among many others:

1777 29 March… Andrews the Smuggler brought me this night about 11 o’ clock a bagg of Hyson Tea, six pounds weight. He frightened us a little by whistling under the parlour window just as we were going to bed. I gave him some Geneva and paid him for the tea at 10/6 per pound…three pounds, three shilling.

Other goods smuggled into the country included wines, spirits and tobacco, while raw wool was shipped to France to take advantage of the high prices it fetched there. Smuggling took place all along the coasts, but flourished in the more remote corners of Dorset, Devon and Cornwall. Therefore, the trading figures for the eighteenth century provide us with a picture of goods legally entering and leaving the country only.

According to family tradition, the most important person of our patronomy was interred at Wimbourne Minster. This was the Dorset smuggler, Isaac Gulliver (b. 1745 in Semington, Wiltshire). He was, in the language of that time, a free-trader, and, when apprehended by the authorities for smuggling, either he, or his defense counsel pleaded that he must see the King (George III) and make some matter known to him for his personal safety. He told the King what he had discovered on his voyages to the low countries, which he suggested the King should take steps in his own personal interest to prove. This the King did straightaway and was apparently very pleased, engaging Gulliver in more secret talks. Our namesake explained that he had to have some means to maintain his ship and crew in good shape and order, but that if allowed, he would see that the King’s interest would be considered. The King gave him the freedom to carry on, pardoning Gulliver for helping to foil an assassination attempt and supplying Nelson with information about the movement of French ships along the coast.

According to family tradition, the most important person of our patronomy was interred at Wimbourne Minster. This was the Dorset smuggler, Isaac Gulliver (b. 1745 in Semington, Wiltshire). He was, in the language of that time, a free-trader, and, when apprehended by the authorities for smuggling, either he, or his defense counsel pleaded that he must see the King (George III) and make some matter known to him for his personal safety. He told the King what he had discovered on his voyages to the low countries, which he suggested the King should take steps in his own personal interest to prove. This the King did straightaway and was apparently very pleased, engaging Gulliver in more secret talks. Our namesake explained that he had to have some means to maintain his ship and crew in good shape and order, but that if allowed, he would see that the King’s interest would be considered. The King gave him the freedom to carry on, pardoning Gulliver for helping to foil an assassination attempt and supplying Nelson with information about the movement of French ships along the coast.

He was also given a considerable parcel of land in the vicinity of Bournemouth and Christchurch, where he could berth his vessel. Well, our man Gulliver took full advantage, and had a crew of first class sailors and men at arms, estimated at anything between two and five hundred in number, dressed in white uniforms. They took three foreign vessels in the Channel, probably French, and it is recorded that it took a train of carts, wagons and pack-horses two miles long to carry the booty away; though, to this day, it is not exactly known to where… (to be continued).

In 1700, England and Wales were still largely agricultural countries. A total population of just five and a half million (the current population of Scotland) lived mostly in small villages and market towns. With a population of 674,000, London was the only sizeable town by modern standards. A medieval peasant transported from the year 1415 to the year 1715 would have found himself still in a familiar landscape. For most people in England at the beginning of the eighteenth century, life still centred around the village where they lived and worked. It was in this small circumference that the farm labourer spent the whole of his life. Villages were sited where the soil was suitable for growing crops or where sheep could be reared. The majority of the population lived, as in medieval times, in the south Midlands, East Anglia and the South East (see map), but even there, where the soil was most fertile, most villages had remained small.

In 1700, England and Wales were still largely agricultural countries. A total population of just five and a half million (the current population of Scotland) lived mostly in small villages and market towns. With a population of 674,000, London was the only sizeable town by modern standards. A medieval peasant transported from the year 1415 to the year 1715 would have found himself still in a familiar landscape. For most people in England at the beginning of the eighteenth century, life still centred around the village where they lived and worked. It was in this small circumference that the farm labourer spent the whole of his life. Villages were sited where the soil was suitable for growing crops or where sheep could be reared. The majority of the population lived, as in medieval times, in the south Midlands, East Anglia and the South East (see map), but even there, where the soil was most fertile, most villages had remained small.We had for dinner a Calf’s head, boiled fowl and tongue, a saddle of mutton roasted on the side table, and a swan roasted with currant jelly sauce for the first course. The second course a couple of wild fowl called dun fowls, larks, blamange, tarts, etc., etc. and a good dessert of fruit after among which was a damson cheese.

Life was precarious for labourers, cottagers and for the smaller farmers. They simply survived from one year to the next with nothing to put by as a surplus to support them in bad times or in their old age. Many families were compelled to seek help from the parish authorities because the man of the house had fallen sick. Rural poverty continued to be the largest single problem in England as the eighteenth century progressed. Only slightly above the growing number of unemployed and unemployable were the mass of those whose earnings were totally inadequate to keep body and soul together. Agricultural labourers were employed on a daily basis at five or six pence a day. In the slack seasons of the year, when the weather was bad and the harvests failed, they had nothing to do but stay at home or beg in the streets of nearby towns.

Life was precarious for labourers, cottagers and for the smaller farmers. They simply survived from one year to the next with nothing to put by as a surplus to support them in bad times or in their old age. Many families were compelled to seek help from the parish authorities because the man of the house had fallen sick. Rural poverty continued to be the largest single problem in England as the eighteenth century progressed. Only slightly above the growing number of unemployed and unemployable were the mass of those whose earnings were totally inadequate to keep body and soul together. Agricultural labourers were employed on a daily basis at five or six pence a day. In the slack seasons of the year, when the weather was bad and the harvests failed, they had nothing to do but stay at home or beg in the streets of nearby towns. There had been a thriving woollen cloth industry since the fourteenth century, with its centre first in East Anglia and then in Yorkshire, based on the domestic system, with workshops and fulling mills, but factories were as yet unknown. Woollen cloth manufactured in England had been sold abroad for generations, with people working in their own homes. The yarn was spun and the cloth woven in cottages and farmhouses throughout the country. The West Country, East Anglia and Yorkshire were the three main centres of cloth production, where spinning and weaving had become full-time occupations for some, and a means of supplementing incomes for many more. Nevertheless, in Suffolk, even when the yarn industry was flourishing, employing about thirty-six thousand women and children, the spinsters were paid only three or four pence for a full day’s work and had to look to the parish for additional help.

There had been a thriving woollen cloth industry since the fourteenth century, with its centre first in East Anglia and then in Yorkshire, based on the domestic system, with workshops and fulling mills, but factories were as yet unknown. Woollen cloth manufactured in England had been sold abroad for generations, with people working in their own homes. The yarn was spun and the cloth woven in cottages and farmhouses throughout the country. The West Country, East Anglia and Yorkshire were the three main centres of cloth production, where spinning and weaving had become full-time occupations for some, and a means of supplementing incomes for many more. Nevertheless, in Suffolk, even when the yarn industry was flourishing, employing about thirty-six thousand women and children, the spinsters were paid only three or four pence for a full day’s work and had to look to the parish for additional help. There were, of course, many degrees and orders of society between the merchant and yeoman farmer and the artisan and casual labourer. In 1752 a carpenter could earn 1s. 10d. and a bricklayer (with mate) 3s 4d. for a day’s work. However, the insecure and short time nature of many rural occupations was clear for all to see and many to experience. Parents who wanted a greater degree of security for their children tried to place them in service. Any family aspiring to some sort of social status kept servants and could afford to do so because wages were so low. The servants accepted their pittance, long hours of work, lack of freedom and the insults of their betters because it would not have occurred to them to do otherwise and because they were reasonably fed, cleanly clothed and, by comparison with their own homes, luxuriously accommodated.

There were, of course, many degrees and orders of society between the merchant and yeoman farmer and the artisan and casual labourer. In 1752 a carpenter could earn 1s. 10d. and a bricklayer (with mate) 3s 4d. for a day’s work. However, the insecure and short time nature of many rural occupations was clear for all to see and many to experience. Parents who wanted a greater degree of security for their children tried to place them in service. Any family aspiring to some sort of social status kept servants and could afford to do so because wages were so low. The servants accepted their pittance, long hours of work, lack of freedom and the insults of their betters because it would not have occurred to them to do otherwise and because they were reasonably fed, cleanly clothed and, by comparison with their own homes, luxuriously accommodated. An inhabitant of the place has counted three hundred droves pass in one season over Stratford Bridge on the River Stour; these droves contain from three hundred to one thousand in each drove, so one may suppose them to contain five hundred one within another, which is a hundred and fifty thousand in all.

An inhabitant of the place has counted three hundred droves pass in one season over Stratford Bridge on the River Stour; these droves contain from three hundred to one thousand in each drove, so one may suppose them to contain five hundred one within another, which is a hundred and fifty thousand in all. In this way the clothiers employed hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of workers. Putters-out were employed to travel round distributing and collecting material, paying wages as they did so. They did not usually go to workers’ homes but would operate from depots set up throughout the area covered by the clothier. The workers would have to carry their material to and fro the barn, inn or shop, which served as their local depot. If foreign trade hit bad times the clothier would simply put out less wool, so that spinners and weavers would be thrown out of work, a cause of considerable complaint amongst them. For their part, the employers frequently complained of the delays caused by the custom of keeping ‘Saint Monday’ free for the alehouse.

In this way the clothiers employed hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of workers. Putters-out were employed to travel round distributing and collecting material, paying wages as they did so. They did not usually go to workers’ homes but would operate from depots set up throughout the area covered by the clothier. The workers would have to carry their material to and fro the barn, inn or shop, which served as their local depot. If foreign trade hit bad times the clothier would simply put out less wool, so that spinners and weavers would be thrown out of work, a cause of considerable complaint amongst them. For their part, the employers frequently complained of the delays caused by the custom of keeping ‘Saint Monday’ free for the alehouse. As early as 1717 Sir Thomas Lombe had set up a silk mill at Derby, which housed three hundred workers Lombe’s building was greatly admired and became the pattern for the cotton factories when they were built, like the famous cotton mill that Richard Arkwright established at nearby Cromford in the 1760s. However, until the latter quarter of the eighteenth century, most industry remained based on the domestic system.

As early as 1717 Sir Thomas Lombe had set up a silk mill at Derby, which housed three hundred workers Lombe’s building was greatly admired and became the pattern for the cotton factories when they were built, like the famous cotton mill that Richard Arkwright established at nearby Cromford in the 1760s. However, until the latter quarter of the eighteenth century, most industry remained based on the domestic system. The Agricultural Revolution took place during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when farmers had to produce more food to feed the growing population of England and Wales. They did this by improving the way they farmed and by cultivating more land. The most important change in this respect was the enclosure of the open fields, which in 1700 still accounted for something like half the arable land in England and Wales. When a village was enclosed each farmer’s land was consolidated into a single holding. This process had been going on for centuries, especially in East Anglia, but in the eighteenth century the enclosure movement accelerated rapidly throughout the whole of southern England and Wales. From 1760 to 1800 Parliament passed over a thousand Acts, and from 1800 to 1815 a further eight hundred. Contemporary reaction to such legislation varied, as did that of historians subsequently. A more detailed investigation of the evidence has revealed an important methodological principle, that it is difficult and dangerous to generalise on to a national scale from local evidence. The locality of agricultural experience determined the particular nature and impact of enclosure within it.

The Agricultural Revolution took place during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries when farmers had to produce more food to feed the growing population of England and Wales. They did this by improving the way they farmed and by cultivating more land. The most important change in this respect was the enclosure of the open fields, which in 1700 still accounted for something like half the arable land in England and Wales. When a village was enclosed each farmer’s land was consolidated into a single holding. This process had been going on for centuries, especially in East Anglia, but in the eighteenth century the enclosure movement accelerated rapidly throughout the whole of southern England and Wales. From 1760 to 1800 Parliament passed over a thousand Acts, and from 1800 to 1815 a further eight hundred. Contemporary reaction to such legislation varied, as did that of historians subsequently. A more detailed investigation of the evidence has revealed an important methodological principle, that it is difficult and dangerous to generalise on to a national scale from local evidence. The locality of agricultural experience determined the particular nature and impact of enclosure within it. Enclosures led to many improvements in farming. For example, they accelerated the spread of new farming methods. One of the most important was the development of new crop rotations to replace the traditional system whereby one field was left fallow each year. Farmers in Norfolk were among the first to discover that fallowing was unnecessary if proper use was made of crops like turnip and clover. These were fodder crops that enabled farmers to keep more livestock, and more animals meant more manure to enrich the soil. Due to this, and the fact that turnips, clover and other small crops enriched the soil, fallowing could be avoided if they were regularly alternated with grain crops. The Norfolk system, or variations of it, had been well established in East Anglia, the Home Counties and much of southern England by 1700. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the new rotations became increasingly popular.

Enclosures led to many improvements in farming. For example, they accelerated the spread of new farming methods. One of the most important was the development of new crop rotations to replace the traditional system whereby one field was left fallow each year. Farmers in Norfolk were among the first to discover that fallowing was unnecessary if proper use was made of crops like turnip and clover. These were fodder crops that enabled farmers to keep more livestock, and more animals meant more manure to enrich the soil. Due to this, and the fact that turnips, clover and other small crops enriched the soil, fallowing could be avoided if they were regularly alternated with grain crops. The Norfolk system, or variations of it, had been well established in East Anglia, the Home Counties and much of southern England by 1700. During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the new rotations became increasingly popular. Sophisticated systems of crop rotation, use of fertilisers, reclamation of waste land, regional specialisation, all these were marks of the new approach to farming. Since they kept more animals, farmers were also able to experiment with scientific, selective stockbreeding. Robert Bakewell was the most famous of a number of men who, by careful breeding, managed to produce much heavier livestock. They had shown not only that attention to diet – and, in particular, the use of root crops for winter feed – produced bigger, healthier animals, but also that it was possible, by in-breeding, to achieve in animals just those characteristics which are required. Suffolk gave the world three great breeds of domestic animals during this period – the Black Face sheep, the Red Poll cow and the Suffolk Punch, the most famous and best-loved of all the Suffolk shire horses. Thomas Crisp of Ufford owned the founding sire, from whom all these noble creatures descend, in the 1760s. In 1784 Sir John Cullum described the qualities of the breed in his History of Hawstead:

Sophisticated systems of crop rotation, use of fertilisers, reclamation of waste land, regional specialisation, all these were marks of the new approach to farming. Since they kept more animals, farmers were also able to experiment with scientific, selective stockbreeding. Robert Bakewell was the most famous of a number of men who, by careful breeding, managed to produce much heavier livestock. They had shown not only that attention to diet – and, in particular, the use of root crops for winter feed – produced bigger, healthier animals, but also that it was possible, by in-breeding, to achieve in animals just those characteristics which are required. Suffolk gave the world three great breeds of domestic animals during this period – the Black Face sheep, the Red Poll cow and the Suffolk Punch, the most famous and best-loved of all the Suffolk shire horses. Thomas Crisp of Ufford owned the founding sire, from whom all these noble creatures descend, in the 1760s. In 1784 Sir John Cullum described the qualities of the breed in his History of Hawstead: Wool was now of little importance to sheep farmers in Suffolk. What they needed were ewes that produced a large number of lambs, with a high meat quality. By the early 1800s it became clear that the best results were obtained by crossing Norfolk horned ewes, traditionally hardy animals, with Southdown rams, famed for their fattening qualities. The offspring were known at first as Blackfaces, but were eventually classified as a distinct breed, Suffolk Sheep. The Earl of Stradbroke was among the early enthusiastic champions of the breed and his famous shepherd Ishmael Cutter produced some remarkable results on the Earl’s pastures near Eye. In 1837 he raised 606 lambs from 413 ewes, a considerable achievement in the days before artificial feedstuffs.