Archive for the ‘Geoffrey Chaucer’ Tag

Above: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Peterborough) for 1137, written c. 1154.

The Transition from Old English to Middle English:

Before the first printing press was set up by William Caxton in 1476, many copies of books were lost. The more popular books, re-written many times, like Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, have survived, although Chaucer’s original manuscripts have been lost. Other works are known through a single surviving copy.

The writings of most early modern authors, from Shakespeare onwards, were prepared for printing in modern editions by editors who almost always converted the original spelling and punctuation into modern standard forms. For example, an early edition of Henry IV Part I printed in 1598 contains the following words spoken by Falstaff:

If I be not ashamed of my soldiours, I am a souct gurnet, I have misused the kinges presse damnablie. No eye hath scene such skarcrowes. Ile not march through Coventry with them, that’s flat.

It contains several unfamiliar features of spelling and punctuation, some of which, like souct gurnet, obscure meaning for the modern reader. It probably means ‘soused’ which has two meanings in modern English, both ‘soaked’ and ‘preserved’ in salted water or ‘pickled’ in vinegar, as in ‘soused herrings’. When we work out that gurnet may mean ‘gherkin’, we begin to make some sense of the phrase. The policy of modernising the spelling and punctuation of old texts which began with the eighteenth century dictionaries has obscured the regional spellings which still existed from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century and the gradual development of a recognisably standard form of spelling in English. Shakespeare, for example, was from Stratford, literally at the crossroads of these dialects, which also explains, in part, his lexical variety. However, few of his plays were printed and published during his lifetime, since they were first written to be performed rather than read. So while the original spellings of Chaucer’s ME manuscripts of 1390s survive into printed text, those of Shakespeare’s manuscripts in the Early Modern English of the 1590s do not. All printed versions of old texts compromise in reproducing the originals, but original handwritten scripts and facsimiles are often difficult to decipher.

The most important change in manuscripts from OE to ME, for example in The Peterborough Chronicle, is found in the absence of many of the inflections of OE, mainly by their reduction in sound. This led to a greater reliance on word order and the more frequent use of prepositions to show the meanings that might formerly have been conveyed by suffixes. The word-for-word translation of the entry for 1137, written in 1154, reveals this transitional phase:

I ne can ne I ne can tell all the

horrors ne all the pains that they caused wretched-men in this land… that lasted the nineteen winters while Stephen was king… ever it were worse and worse…

…then was the corn dear… flesh and cheese and butter… for none ne was in the land…

Wretched-men died of hunger…

…where so one tilled… the earth ne born no corn… for the land was all ruined… with such deeds… they said openly that christ slept and his saints…

Such and more than we can say… we suffered nineteen winters for our sins.

Another noticeable change was the inclusion of a small number of words, significant in their frequency, which were adopted from ‘Anglo-Norman’, the form of Old Northern French spoken by the Normans in England. Most typical are words like castel and prison, but other words which seem to have been adopted into English by the late twelfth century include:

Abbat, capelain, cancelere, cardinal, clerc, cuntesse, curt, duc, iustice, legat, market, prior, rent, serfise, tresor.

(abbot, chaplain, chancellor,… clerk, countess, court, duke, justice, legate,… service, treasure.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of these words were either part of the lexis of administration and law, conducted mainly in Norman French, or that of the Church, conducted in a mixture of Latin and French. Another important source for the shift in the language after 1150 is the book called Ormulum, written by an Anglo-Danish monk named Orm. At the beginning of his book, he explains why he wrote it:

This book is called Ormulum… Because Orm it wrought… (= made)

I have turned into English… (The) gospel’s holy lore… After that little wit that me… My Lord has lent…

(Word-for-word translation)

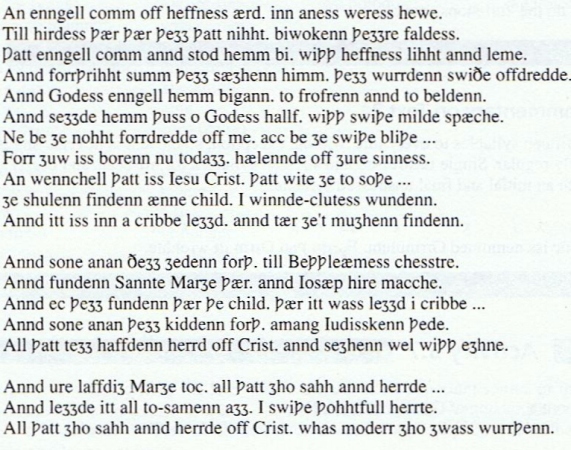

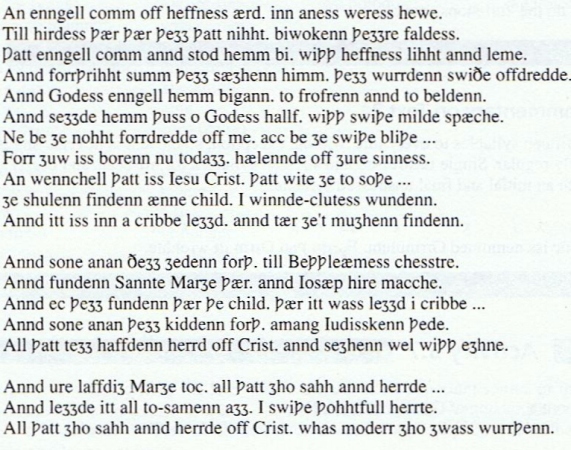

Orm goes on to tell future readers, and to warn future scribes, that he had attempted to write correctly every letter and word in English. Not surprisingly therefore, his spelling is consistent and represents a conscious attempt to reform the system of recording sounds, relating each sound to a symbol. For example, he introduced three symbols for ‘g’ to differentiate the three sounds that it had come to represent, and substitutes ‘wh’ for ‘hw’ in OE, providing forerunners of ‘who’, ‘whose’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘why’ and ‘when’ in Modern English, and ‘sh’ for ‘sc’ in OE, providing ‘shall’ for ‘sceal’ and ‘Englissh’ for ‘Englisc’. In word-for-word translation, here is an extract from Orm’s rendering of Luke’s nativity verses concerning the appearance of the angel to the shepherds:

An angel came from heaven’s land… in a man’s form…

To shepherds there where they that night… watched their folds.

The angel came and stood them by… with heaven’s light and brightness…

And immediately as they saw him… they became very afraid.

And God’s angel them began… to comfort and to encourage…

And said to them thus on God’s behalf… with very mild speech…

Ne be ye not afraid of me… but be ye very blithe …

For to-you is born now today… saviour of our sins…

A child that is Jesus Christ… that know ye for truth …

Ye shall find a child… in swaddling-clothes wound…

And it is in a crib laid… and there ye it may find.

And soon at once they went forth… to Bethlehem’s city…

And found Saint Mary there… and Joseph her husband…

And also they found there the child… where it was laid in crib …

And soon at once they made-known forth… among Jewish nation…

All that they had heard of Christ… and saw well with eyes.

And our lady Mary took… all that she saw and heard …

And laid it all together always… in very thoughtful heart…

All that she saw and heard of Christ… whose mother she was become.

Above: The original text of The Shepherds at the Manger, Ormulum, late twelfth century

Orm’s twenty thousand or so lines of verse are important evidence for some of the changes in the language that had taken effect by the end of the twelfth century in his part of the country. He lived in northern Lincolnshire, now South Humberside, so he wrote in the East Mercian dialect, like the authors of the Peterborough Chronicle continuations. His main objective was to teach the Christian faith in English, and the verses were to be read aloud. His system of spelling was therefore designed to help the reader to pronounce the texts properly. What is especially noticeable is the number of letters he wrote as double consonants. His lines, however, are not great literature, since according to his purpose, they are absolutely regular in metre and therefore monotonous. He is therefore often overlooked even in the limited canon of ME literature, though his writing is very valuable to students of the language.

All present-day dialects of English, including the regional accents in which Standard English may be spoken, can be traced back to the dialects of the ME period (c. 1150-1450) in their pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar. There was no standard form of the language then, and the grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation varied from one part of the country to another, even within distances of twenty miles. Differences in spelling, punctuation, vocabulary and grammar in manuscripts are first-hand evidence of varied usages and forms of pronunciation, and of the changes which took effect over the period. When this evidence is examined systematically, knowledge of the probable dialectal region in which a text was written can be deduced.

Geoffrey Chaucer, writing in the 1390s in the southern Mercian, or London dialect, used the new form of subject pronoun, which by his time had been ‘borrowed’ by the Northern dialect of ME from ON and had spread southwards, but did not become completely assimilated into the Southern dialect until the beginning of the fifteenth century:

And thus they being accorded and ysworn

However, he used the older forms for the object and possessive, as in:

And many a lovely look on hem he caste

Men sholde wedden after hir estaat

The vocabulary of the northern text, Cursor Mundi contains a number of words derived from OE. It was written in the North of England in the last quarter of the thirteenth century. It consists of thirty thousand lines of verse, retelling Christian legends and Bible stories. The following couplet is one indicator of its Northern origins. In the ME original, wrong (in the southern Mercian dialect used later by Chaucer), is ‘wrang’, loth is ‘lath’ and ‘angry’ is ‘wrath’, all three retaining the long /a:/ vowel:

Wrong-doing is loth to hear of justice

And pride is angry with humility

An example of the East Midlands dialect in ME from the thirteenth century worth examining is the only surviving manuscript of the medieval Bestiary, which was based on the belief the animal and plant world was symbolic of religious truths – the creatures of this sensible world signify the invisible things of God. Later scientific knowledge revealed that some of these things were not true of the real animals described, while other animals, like the unicorn, phoenix and basilisk are purely imaginary, the stuff of myths, legends and Harry Potter books! Here is the description of the eagle’s flight in modern word-for-word translation:

Show I wish the eagle’s nature…

How he renews his youth

How he comes out of old age

When his limbs are weak

When his beak is completely twisted

When his flight is all weak

And his eyes dim…

A spring he seeks that flows always

Both by night and by day

Thereover he flies and up he goes

Till that he the heaven sees

Through clouds six and seven

Till he comes to heaven.

As directly as he can

He hovers in the sun.

The sun scorches all his wings

And also it makes his eyes bright.

His feathers fall because of the heat

And he down then to the water …

Falls in the well bottom

Where he becomes hale and sound

And comes out all new …

The variety of ME can be seen in that there were many possible spellings for the same word, according to the period and the dialectal area in which a particular manuscript was copied. For example, the Oxford English Dictionary has the following twenty-seven spellings for ‘shield’ from Old English to Modern English:

scild, scyld, sceld, seld, sseld, sheld, cheld, scheld, sceild, scheeld, cheeld, schuld, scelde, schulde, schylde, shilde, schelde, sheeld, schield, childe, scheild, shild, shylde, sheelde, schielde, sheild, shield.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to find any example of an authentic carol which can with certainty be dated earlier than 1400 (Chaucer’s roundel of c.1382… has to be arranged in order to be sung as a carol)… the oldest of our carols date from the fifteenth century.

The carol was in fact a sign, like the mystery play, of the emancipation of the people from the old puritanism which had for so many centuries suppressed the dance and the drama, denounced communal singing, and warred against the tendency of the people to disport themselves in church on the festivals.

… No doubt in the Middle Ages, as under the Roundheads, such objections often found justification in the excesses of popular merriment. But even in the twelfth century and even in church the instinct for dramatic expression was in revolt, as we find Abbot Aelred of Rievaulx complaining of chanters who gesticulated and grimaced while singing the sacred offices, and imitated the sound of thunder, of women’s voices, and of the neighing of horses. In other and more seemly ways, anthems, sequences and tropes were sung with increasing dramatic emphasis, till from them the mystery play developed. The struggle went on, and the Muses gradually won: about the time when the English barons rose against King John, Pope Innocent III forbad ‘ludi theatrales’ in church, and his order was repeated by Gregory IX. By this time the mystery play had become in many places a real form of drama, performed outside the church. France, which was ahead of England with the play (as Germany seems to have been more than a generation ahead with the carol), had a secular drama in the thirteenth century, four examples of which, by Adam the Hunchback (1288) and others, survive. English drama in the literary sense dates from about the year 1300; the Guilds took up the mystery play and brought it to full flower, gradually increasing the secular element at the same time: the York and Towneley Plays date from 1340 to 1350, the Chester Plays are c. 1400, and the Coventry Plays ran from 1400 to 1450; the old drama thus reached the top of its vigour in the fifteenth century. Such developments led naturally to the writing of religious songs in the vernacular, as in the Coventry Carol… and also to the gradual substitution of folk-song and dance tunes for the winding cadences of liturgical music. The time was ripe for the carol.

The carol arose with the ballad in the fifteenth century, because people wanted something less severe than the old Latin office hymns, something more vivacious than the plainsong melodies. This century rang up the modern era: it was the age of the all-pervading Chaucerian influence and of the spread of humanism in England, where it culminates in the New Learning under Grocyn, Warham, Linacre and Colet: in Italy the fifteenth century began with the full flood of the Renaissance, and Leonardo was in his prime when he ended: before its close, printed books were familiar objects, and the New World had been discovered. Our earliest carols are taken from manuscripts of this century and from the collection which Richard Hill, the grocer’s apprentice… made at the beginning of the sixteenth. The earliest printed collection which has survived (and that only in one of its leaves containing one of the Boar’s Head Carols,… and ‘a caroll of hyntynge’) was issued in 1521 by Wynkyn de Worde, Caxton’s apprentice and successor. A later extant collection was printed by Richard Kele, c.1550.

The carol continued to flourish through the sixteenth century, and until… puritanism in a new form suppressed it in the seventeenth. In the year 1644 the unfortunate people of England had to keep Christmas Day as a fast, because it happened to fall on the last Wednesday in the month – the day which the Long Parliament had ordered to be kept as a monthly fast. In 1647 the Puritan Parliament abolished Christmas and other festivals altogether. The new Puritan point of view is neatly expressed by Hezekiah Woodward, who in a tract of 1656 calls Christmas Day,

‘the old Heathen’s Feasting Day, in honour to Saturn their Idol-God, the Papist’s Massing Day, the Profane Man’s Ranting Day, the Superstitious Man’s Idol Day, the Multitude’s Idle Day, Stan’s – that Adversary’s – Working Day, the True Christian Man’s Fasting Day… We are persuaded, no one thing more hindereth the Gospel work all year long, than doth the observation of that Idol Day once a year, having so many days of cursed observation with it.’

Thus, most of our old carols were made during the two centuries and a half between the death of Chaucer in 1400 and the ejection of the Reverend Robert Herrick from his parish by Oliver Cromwell’s men in 1647.

Meanwhile the old carols travelled underground and were preserved in folk-song, the people’s memory of the texts being kept alive by humble broadsheets of indifferent exactitude which appeared annually in various parts of the country.

The Making of The Mother Tongue: The Emergence of Middle English

The making of the English language is the story of three invasions and a cultural revolution. In the simplest of terms, the language was brought to Britain by Germanic tribes, the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, subtly enriched by British, influenced by Latin and Greek from the Lindisfarne and Augustinian missions, contributed to by Danish, and finally supplemented from Norman French and Flemish.

From the very beginning it was a crafty hybrid, made in war and peace. By the time of Geoffrey Chaucer, it had become an intelligible common language, one that can be interpreted by modern scholars. Native English-speakers in the British Isles have always accepted the mongrel nature of the language as, in the words of Daniel Defoe, “Roman-Saxon-Danish-Norman English”. There was, alongside this, a vague understanding of its membership of a European language family.

From the very beginning it was a crafty hybrid, made in war and peace. By the time of Geoffrey Chaucer, it had become an intelligible common language, one that can be interpreted by modern scholars. Native English-speakers in the British Isles have always accepted the mongrel nature of the language as, in the words of Daniel Defoe, “Roman-Saxon-Danish-Norman English”. There was, alongside this, a vague understanding of its membership of a European language family.

The Hundred Years War with France (1337-1454) provided a major impetus to speak English rather than French. At the same time, the outbreak of The Black Death made labour scarce, thereby accelerating the rise in the status of the English labourer, culminating in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. It caused so many deaths in the monasteries and churches that a new generation of semi-educated, non-French, Latin-speakers took over as abbots and prioresses. After the plague, English grammar began to be taught in schools, to the detriment of French. In 1325, the chronicler William of Nassyngton wrote:

Latin can no one speak, I trow,

But those who it from school do know;

And some know French, but no Latin

Who’re used to Court and dwell therein,

And some use Latin, though in part,

Who if known have not the art,

And some can understand English

That neither Latin knew, nor French

But simple or learned, old or young,

All understand the English tongue.

English now appeared at every level of society. In 1356, the mayor and aldermen of London ordered that court proceedings there be heard in English; in 1362, the Chancellor opened Parliament in English. During the Peasants’ Revolt, Richard II spoke to Wat Tyler, their leader, in English. In the last year of the century, the document by which he was deposed was written in English. Henry IV’s speeches claiming and accepting the throne were also in English. The mother tongue had not only survived, but had become the recognised language of state in England.

By this time, it had taken the form now known by scholars as Middle English, a term devised in the nineteenth century to describe the language from 1150 to 1500. However, this was not a development from Old English writing, like Beowulf, but rather a written form of a more standardised colloquial English, written as spoken, without the inflections and suffixes of the older form, but with prepositions. There were also a great many variations in pronunciation and spelling, especially with vowel sounds. For example, in the case of byrgen, Modern English has kept the western spelling, bury, while using the Kentish pronunciation, berry, while the same noun can also be spelt burgh or borough and pronounced burra in British English and burrow in American English. The language map of England and northern Britain had not changed much from Anglo-Saxon times, though when written down, it developed strong local forms, which in turn reinforced the variety of speech. Early southern authors who wanted their stories to be read in the north as well as south, had to translate for northern people who could read no other English.

By this time, it had taken the form now known by scholars as Middle English, a term devised in the nineteenth century to describe the language from 1150 to 1500. However, this was not a development from Old English writing, like Beowulf, but rather a written form of a more standardised colloquial English, written as spoken, without the inflections and suffixes of the older form, but with prepositions. There were also a great many variations in pronunciation and spelling, especially with vowel sounds. For example, in the case of byrgen, Modern English has kept the western spelling, bury, while using the Kentish pronunciation, berry, while the same noun can also be spelt burgh or borough and pronounced burra in British English and burrow in American English. The language map of England and northern Britain had not changed much from Anglo-Saxon times, though when written down, it developed strong local forms, which in turn reinforced the variety of speech. Early southern authors who wanted their stories to be read in the north as well as south, had to translate for northern people who could read no other English.

Even Chaucer launched his litel book of Troilus and Criseyde with a prayer that all might understand it, for ther is so great diversite… in writying of oure tonge.

Spoken English differed from county to county, from Essex to Suffolk, as it does today, at least in rural shires. The five main speech areas of Middle English; Northern, West and East Midland, Southern and Kentish, are very similar to contemporary English speech areas. Within the Midlands, the areas around and between Oxford, Stratford and Cambridge shared roughly the same kind of English, which became the standard British English of the last six hundred years.

The First ‘Foundeur’… of our English: Geoffrey Chaucer

The career and achievement of one man, Geoffrey Chaucer, exemplifies the triumph of Midland English. By making a conscious decision to write in English, he symbolises the rebirth of English as a national language. Born in 1340 in London, of a middle-class family from Ipswich who had become wealthy in the wine trade, he was educated as a squire in a noble household, later joining the king’s retinue. He began his writing life as a translator and imitator. From 1370 to 1391, Chaucer was busy on the king’s business at home and abroad. He is recorded as negotiating a trade agreement in Genoa, and on a diplomatic mission to Milan, from which he acquired a taste for Italian poetry at a time when Renaissance poetry was in full flower in Florence and other cities. It is likely to have been around this time that he began work on his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales, poems which he would either read aloud, as was customary, or, as was increasingly the practice, pass around for reading. In the final years of his life, Chaucer’s career at court faltered, like many others, due to the divisions into Yorkist and Lancastrian factions. The last reference to him comes in December 1399, when he took a lease on a house in the garden of Westminster Abbey. He was buried in the Abbey in 1400.

The career and achievement of one man, Geoffrey Chaucer, exemplifies the triumph of Midland English. By making a conscious decision to write in English, he symbolises the rebirth of English as a national language. Born in 1340 in London, of a middle-class family from Ipswich who had become wealthy in the wine trade, he was educated as a squire in a noble household, later joining the king’s retinue. He began his writing life as a translator and imitator. From 1370 to 1391, Chaucer was busy on the king’s business at home and abroad. He is recorded as negotiating a trade agreement in Genoa, and on a diplomatic mission to Milan, from which he acquired a taste for Italian poetry at a time when Renaissance poetry was in full flower in Florence and other cities. It is likely to have been around this time that he began work on his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales, poems which he would either read aloud, as was customary, or, as was increasingly the practice, pass around for reading. In the final years of his life, Chaucer’s career at court faltered, like many others, due to the divisions into Yorkist and Lancastrian factions. The last reference to him comes in December 1399, when he took a lease on a house in the garden of Westminster Abbey. He was buried in the Abbey in 1400.

He was recognised as a great poet in his lifetime, in both France and England. He took as his subjects all classes of men and women: the Knight, the Prioress, and the famous Wife of Bath. He was alive to the energy and potential of everyday speech. Chaucer wrote in English, but the language of government was still French. Yet, only seventeen years after his death, Henry V became the first English king since Harold Godwinson to use English in official documents, including his will. In the summer of 1415, Henry crossed the channel to fight the French. In the first letter he dictated on French soil, he chose, symbolically, not to write in the language of his enemies. Henry’s predecessor, Edward III, could only swear in English; now it was the official language of English kings. His example made an impression on his people. In a resolution made by the London brewers in the year of Henry’s death, 1422, they decided to adopt English in written form.

He was recognised as a great poet in his lifetime, in both France and England. He took as his subjects all classes of men and women: the Knight, the Prioress, and the famous Wife of Bath. He was alive to the energy and potential of everyday speech. Chaucer wrote in English, but the language of government was still French. Yet, only seventeen years after his death, Henry V became the first English king since Harold Godwinson to use English in official documents, including his will. In the summer of 1415, Henry crossed the channel to fight the French. In the first letter he dictated on French soil, he chose, symbolically, not to write in the language of his enemies. Henry’s predecessor, Edward III, could only swear in English; now it was the official language of English kings. His example made an impression on his people. In a resolution made by the London brewers in the year of Henry’s death, 1422, they decided to adopt English in written form.

The next step was the adoption of the language in printed form, and for this development we must look at the life and work of William Caxton, who printed the work of Geoffrey Chaucer. Caxton was born and learnt his native tongue in the Weald of Kent, where I doubt not is spoken as broad and rude English as in any place of England. He had a career as a merchant and diplomat, learning the art of printing on the continent and then retired, introducing the press into England around the year 1476, setting up the first one in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. Besides Chaucer, he printed the works of other poets like Gower, Lydgate and Malory; but he also translated best sellers from France and Burgundy, and also wrote and printed his own works. When Caxton settled for reproducing the idiosyncrasies he heard in the streets of London, he and other printers helped to fix the written language before its writers and teachers had reached a consensus. It is to this that English owes many of its chaotic and exasperating spelling conventions.

The next step was the adoption of the language in printed form, and for this development we must look at the life and work of William Caxton, who printed the work of Geoffrey Chaucer. Caxton was born and learnt his native tongue in the Weald of Kent, where I doubt not is spoken as broad and rude English as in any place of England. He had a career as a merchant and diplomat, learning the art of printing on the continent and then retired, introducing the press into England around the year 1476, setting up the first one in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. Besides Chaucer, he printed the works of other poets like Gower, Lydgate and Malory; but he also translated best sellers from France and Burgundy, and also wrote and printed his own works. When Caxton settled for reproducing the idiosyncrasies he heard in the streets of London, he and other printers helped to fix the written language before its writers and teachers had reached a consensus. It is to this that English owes many of its chaotic and exasperating spelling conventions.

The Golafres of Suffolk, Berkshire and Oxon.

Chaucer might very well have based the fictional elements of his knight in The Canterbury Tales on Sir John Golafre, keeper of the King’s Jewels and Plate, and the closest friend and confidant of Richard II. Sir John was the bastard son of Sir John Golafre junior of Fyfield Manor in Berkshire, by his mistress, a leman called Johanet Pulham. His father, Sir John senior was fourth in succession from Sir Roger Goulafre, who had acquired the Manor of Sarsden in the reign of King John. By the fourteenth century, besides continuing to hold the manors granted to them by the Conqueror, the Golafre family had acquired lands in Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire and Worcestershire. They appeared on the Swan Rolls, which was a sign of great wealth and heritage. Sir John Golafre senior lived on the manor of Fyfield (then in Berkshire, now Oxon).

Chaucer might very well have based the fictional elements of his knight in The Canterbury Tales on Sir John Golafre, keeper of the King’s Jewels and Plate, and the closest friend and confidant of Richard II. Sir John was the bastard son of Sir John Golafre junior of Fyfield Manor in Berkshire, by his mistress, a leman called Johanet Pulham. His father, Sir John senior was fourth in succession from Sir Roger Goulafre, who had acquired the Manor of Sarsden in the reign of King John. By the fourteenth century, besides continuing to hold the manors granted to them by the Conqueror, the Golafre family had acquired lands in Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire and Worcestershire. They appeared on the Swan Rolls, which was a sign of great wealth and heritage. Sir John Golafre senior lived on the manor of Fyfield (then in Berkshire, now Oxon).

In 1336, he had inherited the manor from his mother-in-law, Juliana, widow of Sir John de Fyfield. His father, Thomas Golafre, of Sarsden, had been MP for Northampton. The manor house on the village green was probably mostly built by this Sir John Golafre senior, who became an MP for Oxfordshire in 1334, then for Worcestershire in 1337-8, where he seems to have inherited lands at Nafford, becoming the member for Oxon once more in 1340. He died in 1363, leaving the estate to his son, Sir John Golafre (junior). Sir John junior’s relationship with his mistress must have lasted a number of years, since there were also, apparently, two daughters by her, Alice, who became the Prioress of Burnham Priory in Buckinghamshire, and Juliana, who married Robert de Wytham (see below). Sir John Golafre junior died in 1378, leaving no legitimate children, so that Fyfield passed first to his brother, Thomas, and then, when he died the following year, it came eventually to Thomas’ son, John Golafre, who occupied it from 1406.

However, despite Sir John junior having no other offspring by his two marriages, his legal heir was his nephew, also John, so his bastard son stood little chance of inheriting any of the widespread estates in the southern Midlands and northern Wessex. John the bastard therefore looked to a career in Royal service to make his way in life and he was probably helped in this by his stepmother’s brother, the Master of the King’s Horse, Sir Bernard Brocas. He almost certainly started out as a soldier in the King’s army, serving in France. By 1384, however, John had obtained a placement in the household of King Richard II and was made an Esquire of the King’s Chamber. The following year, John fought bravely with King Richard’s forces during their invasion of Scotland and, there, he was knighted. This clearly brought him to the fore in the King’s favour and, in 1387, he was sent on Royal diplomatic missions, as well as being appointed to the trusted position of Keeper of the King’s Jewels and Plate. Although Sir John was illegitimate, he married one of the co-heiresses of Dunster, Philippa de Mohun. He may have hoped that such a good marriage would help him acquire land. However, when he married Philippa, her mother, Lady FitzWalter, sold off most of her daughters’ inheritance before she could claim it.

Golafre was employed in an embassy to France, in 1389 where he was to act on behalf of King Richard to organise peace negotiations with King Charles VI. However, this brought him into conflict with the Duke of Gloucester and the other English nobles opposed to the ending of War. In the December, orders were issued for his arrest and he was obliged to stay abroad for some time. The eventual French truce agreed in 1389 meant there were now limited opportunities for armed campaigning, but he kept his hand in on the tournament circuit. In March/April 1390, he is recorded amongst the English knights at the famous St. Inglevert tournament near Calais, where Jean Boucicault and his friends challenged all comers, and he rode against Sir Reginald de Roye. They smashed each other’s helmets in the first round, but neither was unhelmed and their lances also survived serious damage. In the second, their horses refused to charge, but, in the third, they struck shields and broke their lances. There were no strikes in the last round and the two retired from the tilting yard.

Back in England, Sir John managed to acquire positions controlling more static military installations. He was appointed Constable of Wallingford Castle in 1389, followed by Flint Castle in North Wales and Nottingham Castle in the Midlands by 1392. In that year, he was also made responsible for ensuring that all yeomen in the King’s household had bows and regular archery practice, so they could act as Richard’s personal bodyguard. Sir John was also made Captain of Cherbourg and continued with his diplomatic duties abroad. In 1394, he was sent to Poland to gather support for the Anglo-French crusade against the Turks. He was away from home for a whole year but, while the exact results of his mission are unknown, few Poles appear to have joined the cause. The following year, he accompanied the King’s forces on their two expeditions to Ireland.

Back in England, Sir John managed to acquire positions controlling more static military installations. He was appointed Constable of Wallingford Castle in 1389, followed by Flint Castle in North Wales and Nottingham Castle in the Midlands by 1392. In that year, he was also made responsible for ensuring that all yeomen in the King’s household had bows and regular archery practice, so they could act as Richard’s personal bodyguard. Sir John was also made Captain of Cherbourg and continued with his diplomatic duties abroad. In 1394, he was sent to Poland to gather support for the Anglo-French crusade against the Turks. He was away from home for a whole year but, while the exact results of his mission are unknown, few Poles appear to have joined the cause. The following year, he accompanied the King’s forces on their two expeditions to Ireland.

Sir John eventually died at Wallingford Castle on 18th November 1396, aged only about forty-five. He had asked to be buried in the family mausoleum at the Greyfriars’ Church in Oxford but, on his deathbed, King Richard persuaded him that Westminster Abbey was a more fitting site. He was therefore laid to rest under a fine memorial brass adjoining both the shrine of St. Edward and the plot allocated to the King. He left no children but, in his will, he remembered a number of family members, as well leaving the King his best horse, his white-hart badge, gold cup, gold chain and sapphire encrusted stone.

Above left: A 1912 plan of Wallingford Castle: A – Wallingford bridge and ford; B – River Thames; C – city defences; D – bailey; E – motte

The career of Sir John Golafre (junior) overlaps with that of his bastard cousin, and his life runs in parallel with the continuing rise of the Chaucer family and their intermarriage with the de la Poles. This Sir John was the only son of Sir Thomas Golafre (d. 1378) of Radley Manor in Berkshire, by his wife, Margaret, the daughter of Thomas Foxley of Bray, Constable of Windsor Castle. He was the nephew of Sir John Brocas, the Master of the King’s Horse. As his father was a younger son, he, at first, was set to inherit only modest estates in mid-Berkshire but, upon his Uncle John’s death in 1378, followed by his father’s death the next year, he was given considerably more, centred on Fyfield Manor. Through his bastard cousin, King Richard II’s closest friend, he also obtained a position as a squire at the Royal Court in 1395. Unfortunately, his cousin died the following year, but his widow, Philippa (de Mohun), remarried to the King’s cousin, Edmund, the 2nd Duke of York. John was therefore able to retain close connections with the Royal family.

In 1397, after the King’s revenge had been acted out on the Lords Appellant who had tried to curtail his power, John was appointed Sheriff of Berkshire and Oxfordshire. He was elected Knight of the Shire (MP) for Oxfordshire in the same year and, subsequently, became one of the commissioners exercising parliamentary power after Parliament’s dissolution. During the troubles of 1399, John initially continued to support King Richard and he was thrown in prison when the monarch was captured by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke. However, when he took the throne as King Henry IV, John found himself obliged to accept the situation and he was allowed to remain sheriff until a successor was found. His various Royal annuities were also quickly re-confirmed, though he was dropped from the Oxfordshire Commission of Peace.

John was elected Knight of the Shire (MP) for Berkshire in 1401, a position he held twelve times over the next thirty years. That same year he married the Earl of Suffolk’s niece, Elizabeth, the daughter of Sir Edmund de la Pole of Boarstall Castle in Buckinghamshire. It was the first of three very lucrative marriages for John, although this one did not last long. Elizabeth died, possibly in childbirth, in 1403. The following year, he married Nicola, the daughter & heiress of Thomas Devonish of Greatham in Hampshire and widow of John Englefield (d. 1403) of Englefield House.

By 1408, John had become a close associate of perhaps the most influential man in the local area, Thomas Chaucer, the Constable of Wallingford Castle (in succession to John’s cousin) and sometime Speaker of the House of Commons, as well as his future son-in-law, the Earl of Salisbury. They were involved in numerous land deals together and Chaucer appointed Golafre as Controller and Overseer of Woodstock Palace in Oxfordshire. By 1416, John had risen, not only in the estimations of Royalty and nobility, but also in those of all local people, for he was one of the members of the Fraternity of the Holy Cross who made a large contribution to the building of the first Abingdon Bridge. This greatly boosted trade in the town as merchants no longer had to cross the Thames at Wallingford.

Thomas Chaucer (c. 1367 – 18 November 1434), the son of Geoffrey Chaucer and Philippa Roet, seems to have done well from his father’s standing (as both a poet and also an administrator), despite suggestions that Geoffrey Chaucer fell out of favour with Henry IV. Early in life Thomas Chaucer married Matilda (Maud), second daughter and co-heiress of Sir John Burghersh. The marriage brought him large estates, and among them the manor of Ewelme, Oxfordshire. His connection with the Duke of Lancaster was also profitable to him: his mother’s sister, Katherine Swynford, was first the mistress of John of Gaunt, and then his third Duchess of Lancaster. She had four children by John of Gaunt. While Thomas became Duke of Exeter, Joan became Countess of Westmorland and was grandmother of Kings Edward IV and Richard III. Thomas Chaucer’s Beaufort first cousins became even more powerful when their half-brother Henry IV became King. Thomas was able to buy Donnington Castle for his only daughter Alice.

He was Chief Butler of England for almost thirty years, first appointed by Richard II, and on 20 March 1399 received a pension of twenty marks a year in exchange for offices granted him by the Duke, paying at the same time five marks for the confirmation of two annuities of charges on the Duchy of Lancaster and also granted by the Duke. These annuities were confirmed to him by Henry IV, who appointed him constable of Wallingford Castle, and steward of the honours of Wallingford and St. Valery and of the Chiltern Hundreds. At about the same time, he succeeded Geoffrey Chaucer as forester of North Petherton Park in Somerset. On 5 November 1402 he received a grant of the chief butlership for life.

He served as High Sheriff of Berkshire and Oxfordshire for 1400 and 1403 and as High Sheriff of Hampshire for 1413. He attended fifteen parliaments as knight of the shire for Oxfordshire between 1400 and 1431, and was Speaker of the House five times, a feat not surpassed until the 18th century.

In 1414 he also received a commission, in which he is called domicellus, to treat about the marriage of Henry V, and to take the homage of the Duke of Burgundy. A year later he served with the king in France, bringing into the field 12 men-at-arms and 37 archers, and was present at the Battle of Agincourt. In 1417 he was employed to treat for peace with France. On the accession of Henry VI he appears to have been superseded in the chief butlership, and to have regained it shortly afterwards. Thomas Chaucer died at Ewelme Palace in the village of Ewelme, Oxfordshire on 18 November 1434 and is buried in St Mary’s church in the village.

Land transactions with the great and the good continued throughout the 1420s and 30s, including with Chaucer’s daughter, Alice (right), and her third husband, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, a cousin of John’s first wife. The later transactions, releases and demises for the Suffolk manors are listed in Copinger (1905), and include the following:

Land transactions with the great and the good continued throughout the 1420s and 30s, including with Chaucer’s daughter, Alice (right), and her third husband, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, a cousin of John’s first wife. The later transactions, releases and demises for the Suffolk manors are listed in Copinger (1905), and include the following:

Wingfield Old Hall Manor:

1408 – vested in Michael de la Pole and included in the release and demise of 1430-31 (above) in which John Golafre is again included. 1415 – Michael de la Pole, 2nd Earl of Suffolk, died at Harfleur, of plague, just before the Battle of Agincourt (25th October), aged 23, with no male heir. The manor passed to his brother who became fourth earl of Suffolk, created Duke of Suffolk in June 1448. Foeffees included John Golafre. William de la Pole was beheaded and buried at sea in May 1449, so the manor passed to Alice, grand-daughter of Geoffrey Chaucer (his son Thomas, was powerful in the realm).

Manor of Stradbroke with Stubcroft:

1430 – Manor passed into De la Pole family by marriage prior to death of Michael de la Pole in 1415. In 1430 it was included in a release of all right from Henry Beaufort, Cardinal; Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick; …. John Golafre. It was also included in a deed of 1431 by which they were granted a demise of this and other manors (a demise is the agreed transfer of an estate, especially by lease, with a covenant for quiet enjoyment).

The continuing De la Pole connection soon led, in 1434, to Sir John Golafre’s third marriage to Margaret, daughter of Sir John Heveningham and widow of Sir Walter de la Pole of Dernford at Sawston in Cambridgeshire, who was his first wife’s half-brother. In old age, John was again one of chief members of the Fraternity of the Holy Cross in Abingdon who funded public works, this time the erection of the famous Market Cross in the town in 1438. It is said to have been designed by his friend, Thomas Chaucer, who had died four years earlier. Lysons records the following details:

Sir John died seised of the manor of Fyfield, in 1442. The same year a licence was granted by the Crown, for the foundation of a chantry, at the altar of St. John the Baptist, pursuant to the will of Sir John Golafre, who is styled in the charter servant to King Henry V and King Henry VI. … In the N. aisle of the parish church is the monument of this Sir John, who died in 1442. His effigy in armour lies on an open altar tomb, beneath which is the figure of a skeleton in a shroud. The common people call it Gulliver’s tomb, and say that the figure on the top represents him in the vigour of youth; the skeleton in his old age; the arms of Golafre are on the tomb, and in the windows of the church.

Sir John died seised of the manor of Fyfield, in 1442. The same year a licence was granted by the Crown, for the foundation of a chantry, at the altar of St. John the Baptist, pursuant to the will of Sir John Golafre, who is styled in the charter servant to King Henry V and King Henry VI. … In the N. aisle of the parish church is the monument of this Sir John, who died in 1442. His effigy in armour lies on an open altar tomb, beneath which is the figure of a skeleton in a shroud. The common people call it Gulliver’s tomb, and say that the figure on the top represents him in the vigour of youth; the skeleton in his old age; the arms of Golafre are on the tomb, and in the windows of the church.

Margaret, his third wife, appears to have survived, and the property seems to have passed briefly to Agnes Wytham, who died in 1444. In 1448, it came through the former in-laws of the Golafres, Wiliam and John de la Poles, to John, Earl of Lincoln. Born some time between 1462 and 1464, the son of John, second Duke of Suffolk and Elizabeth of York, he had been created Earl of Lincoln by his uncle, Edward IV. After Edward’s death, his other royal uncle, Richard III, made him heir to the throne in the last year of his reign. He was also grandson of Alice Chaucer, grand-daughter of the great poet. Lincoln was killed at the Battle of Stoke Field of 1487, which ended his Yorkist Rebellion against Henry VII, and with it the Wars of the Roses. He was posthumously attained for treason and his estates, including both Fyfield and Ewelme, the main seat of the Oxfordshire de la Poles, were confiscated by the crown.

Margaret, his third wife, appears to have survived, and the property seems to have passed briefly to Agnes Wytham, who died in 1444. In 1448, it came through the former in-laws of the Golafres, Wiliam and John de la Poles, to John, Earl of Lincoln. Born some time between 1462 and 1464, the son of John, second Duke of Suffolk and Elizabeth of York, he had been created Earl of Lincoln by his uncle, Edward IV. After Edward’s death, his other royal uncle, Richard III, made him heir to the throne in the last year of his reign. He was also grandson of Alice Chaucer, grand-daughter of the great poet. Lincoln was killed at the Battle of Stoke Field of 1487, which ended his Yorkist Rebellion against Henry VII, and with it the Wars of the Roses. He was posthumously attained for treason and his estates, including both Fyfield and Ewelme, the main seat of the Oxfordshire de la Poles, were confiscated by the crown.

(to be continued…)

Sources (see part two)

From the very beginning it was a crafty hybrid, made in war and peace. By the time of Geoffrey Chaucer, it had become an intelligible common language, one that can be interpreted by modern scholars. Native English-speakers in the British Isles have always accepted the mongrel nature of the language as, in the words of Daniel Defoe, “Roman-Saxon-Danish-Norman English”. There was, alongside this, a vague understanding of its membership of a European language family.

From the very beginning it was a crafty hybrid, made in war and peace. By the time of Geoffrey Chaucer, it had become an intelligible common language, one that can be interpreted by modern scholars. Native English-speakers in the British Isles have always accepted the mongrel nature of the language as, in the words of Daniel Defoe, “Roman-Saxon-Danish-Norman English”. There was, alongside this, a vague understanding of its membership of a European language family. By this time, it had taken the form now known by scholars as Middle English, a term devised in the nineteenth century to describe the language from 1150 to 1500. However, this was not a development from Old English writing, like Beowulf, but rather a written form of a more standardised colloquial English, written as spoken, without the inflections and suffixes of the older form, but with prepositions. There were also a great many variations in pronunciation and spelling, especially with vowel sounds. For example, in the case of byrgen, Modern English has kept the western spelling, bury, while using the Kentish pronunciation, berry, while the same noun can also be spelt burgh or borough and pronounced burra in British English and burrow in American English. The language map of England and northern Britain had not changed much from Anglo-Saxon times, though when written down, it developed strong local forms, which in turn reinforced the variety of speech. Early southern authors who wanted their stories to be read in the north as well as south, had to translate for northern people who could read no other English.

By this time, it had taken the form now known by scholars as Middle English, a term devised in the nineteenth century to describe the language from 1150 to 1500. However, this was not a development from Old English writing, like Beowulf, but rather a written form of a more standardised colloquial English, written as spoken, without the inflections and suffixes of the older form, but with prepositions. There were also a great many variations in pronunciation and spelling, especially with vowel sounds. For example, in the case of byrgen, Modern English has kept the western spelling, bury, while using the Kentish pronunciation, berry, while the same noun can also be spelt burgh or borough and pronounced burra in British English and burrow in American English. The language map of England and northern Britain had not changed much from Anglo-Saxon times, though when written down, it developed strong local forms, which in turn reinforced the variety of speech. Early southern authors who wanted their stories to be read in the north as well as south, had to translate for northern people who could read no other English.  The career and achievement of one man, Geoffrey Chaucer, exemplifies the triumph of Midland English. By making a conscious decision to write in English, he symbolises the rebirth of English as a national language. Born in 1340 in London, of a middle-class family from Ipswich who had become wealthy in the wine trade, he was educated as a squire in a noble household, later joining the king’s retinue. He began his writing life as a translator and imitator. From 1370 to 1391, Chaucer was busy on the king’s business at home and abroad. He is recorded as negotiating a trade agreement in Genoa, and on a diplomatic mission to Milan, from which he acquired a taste for Italian poetry at a time when Renaissance poetry was in full flower in Florence and other cities. It is likely to have been around this time that he began work on his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales, poems which he would either read aloud, as was customary, or, as was increasingly the practice, pass around for reading. In the final years of his life, Chaucer’s career at court faltered, like many others, due to the divisions into Yorkist and Lancastrian factions. The last reference to him comes in December 1399, when he took a lease on a house in the garden of Westminster Abbey. He was buried in the Abbey in 1400.

The career and achievement of one man, Geoffrey Chaucer, exemplifies the triumph of Midland English. By making a conscious decision to write in English, he symbolises the rebirth of English as a national language. Born in 1340 in London, of a middle-class family from Ipswich who had become wealthy in the wine trade, he was educated as a squire in a noble household, later joining the king’s retinue. He began his writing life as a translator and imitator. From 1370 to 1391, Chaucer was busy on the king’s business at home and abroad. He is recorded as negotiating a trade agreement in Genoa, and on a diplomatic mission to Milan, from which he acquired a taste for Italian poetry at a time when Renaissance poetry was in full flower in Florence and other cities. It is likely to have been around this time that he began work on his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales, poems which he would either read aloud, as was customary, or, as was increasingly the practice, pass around for reading. In the final years of his life, Chaucer’s career at court faltered, like many others, due to the divisions into Yorkist and Lancastrian factions. The last reference to him comes in December 1399, when he took a lease on a house in the garden of Westminster Abbey. He was buried in the Abbey in 1400. He was recognised as a great poet in his lifetime, in both France and England. He took as his subjects all classes of men and women: the Knight, the Prioress, and the famous Wife of Bath. He was alive to the energy and potential of everyday speech. Chaucer wrote in English, but the language of government was still French. Yet, only seventeen years after his death, Henry V became the first English king since Harold Godwinson to use English in official documents, including his will. In the summer of 1415, Henry crossed the channel to fight the French. In the first letter he dictated on French soil, he chose, symbolically, not to write in the language of his enemies. Henry’s predecessor, Edward III, could only swear in English; now it was the official language of English kings. His example made an impression on his people. In a resolution made by the London brewers in the year of Henry’s death, 1422, they decided to adopt English in written form.

He was recognised as a great poet in his lifetime, in both France and England. He took as his subjects all classes of men and women: the Knight, the Prioress, and the famous Wife of Bath. He was alive to the energy and potential of everyday speech. Chaucer wrote in English, but the language of government was still French. Yet, only seventeen years after his death, Henry V became the first English king since Harold Godwinson to use English in official documents, including his will. In the summer of 1415, Henry crossed the channel to fight the French. In the first letter he dictated on French soil, he chose, symbolically, not to write in the language of his enemies. Henry’s predecessor, Edward III, could only swear in English; now it was the official language of English kings. His example made an impression on his people. In a resolution made by the London brewers in the year of Henry’s death, 1422, they decided to adopt English in written form. The next step was the adoption of the language in printed form, and for this development we must look at the life and work of William Caxton, who printed the work of Geoffrey Chaucer. Caxton was born and learnt his native tongue in the Weald of Kent, where I doubt not is spoken as broad and rude English as in any place of England. He had a career as a merchant and diplomat, learning the art of printing on the continent and then retired, introducing the press into England around the year 1476, setting up the first one in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. Besides Chaucer, he printed the works of other poets like Gower, Lydgate and Malory; but he also translated best sellers from France and Burgundy, and also wrote and printed his own works. When Caxton settled for reproducing the idiosyncrasies he heard in the streets of London, he and other printers helped to fix the written language before its writers and teachers had reached a consensus. It is to this that English owes many of its chaotic and exasperating spelling conventions.

The next step was the adoption of the language in printed form, and for this development we must look at the life and work of William Caxton, who printed the work of Geoffrey Chaucer. Caxton was born and learnt his native tongue in the Weald of Kent, where I doubt not is spoken as broad and rude English as in any place of England. He had a career as a merchant and diplomat, learning the art of printing on the continent and then retired, introducing the press into England around the year 1476, setting up the first one in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. Besides Chaucer, he printed the works of other poets like Gower, Lydgate and Malory; but he also translated best sellers from France and Burgundy, and also wrote and printed his own works. When Caxton settled for reproducing the idiosyncrasies he heard in the streets of London, he and other printers helped to fix the written language before its writers and teachers had reached a consensus. It is to this that English owes many of its chaotic and exasperating spelling conventions. Chaucer might very well have based the fictional elements of his knight in The Canterbury Tales on Sir John Golafre, keeper of the King’s Jewels and Plate, and the closest friend and confidant of Richard II. Sir John was the bastard son of Sir John Golafre junior of Fyfield Manor in Berkshire, by his mistress, a leman called Johanet Pulham. His father, Sir John senior was fourth in succession from Sir Roger Goulafre, who had acquired the Manor of Sarsden in the reign of King John. By the fourteenth century, besides continuing to hold the manors granted to them by the Conqueror, the Golafre family had acquired lands in Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire and Worcestershire. They appeared on the Swan Rolls, which was a sign of great wealth and heritage. Sir John Golafre senior lived on the manor of Fyfield (then in Berkshire, now Oxon).

Chaucer might very well have based the fictional elements of his knight in The Canterbury Tales on Sir John Golafre, keeper of the King’s Jewels and Plate, and the closest friend and confidant of Richard II. Sir John was the bastard son of Sir John Golafre junior of Fyfield Manor in Berkshire, by his mistress, a leman called Johanet Pulham. His father, Sir John senior was fourth in succession from Sir Roger Goulafre, who had acquired the Manor of Sarsden in the reign of King John. By the fourteenth century, besides continuing to hold the manors granted to them by the Conqueror, the Golafre family had acquired lands in Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire and Worcestershire. They appeared on the Swan Rolls, which was a sign of great wealth and heritage. Sir John Golafre senior lived on the manor of Fyfield (then in Berkshire, now Oxon).

Back in England, Sir John managed to acquire positions controlling more static military installations. He was appointed Constable of Wallingford Castle in 1389, followed by Flint Castle in North Wales and Nottingham Castle in the Midlands by 1392. In that year, he was also made responsible for ensuring that all yeomen in the King’s household had bows and regular archery practice, so they could act as Richard’s personal bodyguard. Sir John was also made Captain of Cherbourg and continued with his diplomatic duties abroad. In 1394, he was sent to Poland to gather support for the Anglo-French crusade against the Turks. He was away from home for a whole year but, while the exact results of his mission are unknown, few Poles appear to have joined the cause. The following year, he accompanied the King’s forces on their two expeditions to Ireland.

Back in England, Sir John managed to acquire positions controlling more static military installations. He was appointed Constable of Wallingford Castle in 1389, followed by Flint Castle in North Wales and Nottingham Castle in the Midlands by 1392. In that year, he was also made responsible for ensuring that all yeomen in the King’s household had bows and regular archery practice, so they could act as Richard’s personal bodyguard. Sir John was also made Captain of Cherbourg and continued with his diplomatic duties abroad. In 1394, he was sent to Poland to gather support for the Anglo-French crusade against the Turks. He was away from home for a whole year but, while the exact results of his mission are unknown, few Poles appear to have joined the cause. The following year, he accompanied the King’s forces on their two expeditions to Ireland. Land transactions with the great and the good continued throughout the 1420s and 30s, including with Chaucer’s daughter, Alice (right), and her third husband, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, a cousin of John’s first wife. The later transactions, releases and demises for the Suffolk manors are listed in Copinger (1905), and include the following:

Land transactions with the great and the good continued throughout the 1420s and 30s, including with Chaucer’s daughter, Alice (right), and her third husband, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, a cousin of John’s first wife. The later transactions, releases and demises for the Suffolk manors are listed in Copinger (1905), and include the following: Sir John died seised of the manor of Fyfield, in 1442. The same year a licence was granted by the Crown, for the foundation of a chantry, at the altar of St. John the Baptist, pursuant to the will of Sir John Golafre, who is styled in the charter servant to King Henry V and King Henry VI. … In the N. aisle of the parish church is the monument of this Sir John, who died in 1442. His effigy in armour lies on an open altar tomb, beneath which is the figure of a skeleton in a shroud. The common people call it Gulliver’s tomb, and say that the figure on the top represents him in the vigour of youth; the skeleton in his old age; the arms of Golafre are on the tomb, and in the windows of the church.

Sir John died seised of the manor of Fyfield, in 1442. The same year a licence was granted by the Crown, for the foundation of a chantry, at the altar of St. John the Baptist, pursuant to the will of Sir John Golafre, who is styled in the charter servant to King Henry V and King Henry VI. … In the N. aisle of the parish church is the monument of this Sir John, who died in 1442. His effigy in armour lies on an open altar tomb, beneath which is the figure of a skeleton in a shroud. The common people call it Gulliver’s tomb, and say that the figure on the top represents him in the vigour of youth; the skeleton in his old age; the arms of Golafre are on the tomb, and in the windows of the church. Margaret, his third wife, appears to have survived, and the property seems to have passed briefly to Agnes Wytham, who died in 1444. In 1448, it came through the former in-laws of the Golafres, Wiliam and John de la Poles, to John, Earl of Lincoln. Born some time between 1462 and 1464, the son of John, second Duke of Suffolk and Elizabeth of York, he had been created Earl of Lincoln by his uncle, Edward IV. After Edward’s death, his other royal uncle, Richard III, made him heir to the throne in the last year of his reign. He was also grandson of Alice Chaucer, grand-daughter of the great poet. Lincoln was killed at the Battle of Stoke Field of 1487, which ended his Yorkist Rebellion against Henry VII, and with it the Wars of the Roses. He was posthumously attained for treason and his estates, including both Fyfield and Ewelme, the main seat of the Oxfordshire de la Poles, were confiscated by the crown.

Margaret, his third wife, appears to have survived, and the property seems to have passed briefly to Agnes Wytham, who died in 1444. In 1448, it came through the former in-laws of the Golafres, Wiliam and John de la Poles, to John, Earl of Lincoln. Born some time between 1462 and 1464, the son of John, second Duke of Suffolk and Elizabeth of York, he had been created Earl of Lincoln by his uncle, Edward IV. After Edward’s death, his other royal uncle, Richard III, made him heir to the throne in the last year of his reign. He was also grandson of Alice Chaucer, grand-daughter of the great poet. Lincoln was killed at the Battle of Stoke Field of 1487, which ended his Yorkist Rebellion against Henry VII, and with it the Wars of the Roses. He was posthumously attained for treason and his estates, including both Fyfield and Ewelme, the main seat of the Oxfordshire de la Poles, were confiscated by the crown.

You must be logged in to post a comment.