Archive for the ‘Cartoons’ Category

The Decline of the Liberals & Break-up of the Coalition:

By the end of 1922, the Liberal Party had been relegated to the position of a minor party. Despite the promises of David Lloyd George (right) to provide ‘homes fit for heroes to live in’, it had been slow to develop the effective policies needed for dealing with the economic and social problems created by the First World War; promises based on moralistic liberal ideals were not enough. But there were many among their Coalition partners, the Conservatives, who were more concerned to keep the threat from Labour at bay than to jettison Lloyd George as their popular and charismatic Prime Minister.

By the end of 1922, the Liberal Party had been relegated to the position of a minor party. Despite the promises of David Lloyd George (right) to provide ‘homes fit for heroes to live in’, it had been slow to develop the effective policies needed for dealing with the economic and social problems created by the First World War; promises based on moralistic liberal ideals were not enough. But there were many among their Coalition partners, the Conservatives, who were more concerned to keep the threat from Labour at bay than to jettison Lloyd George as their popular and charismatic Prime Minister.

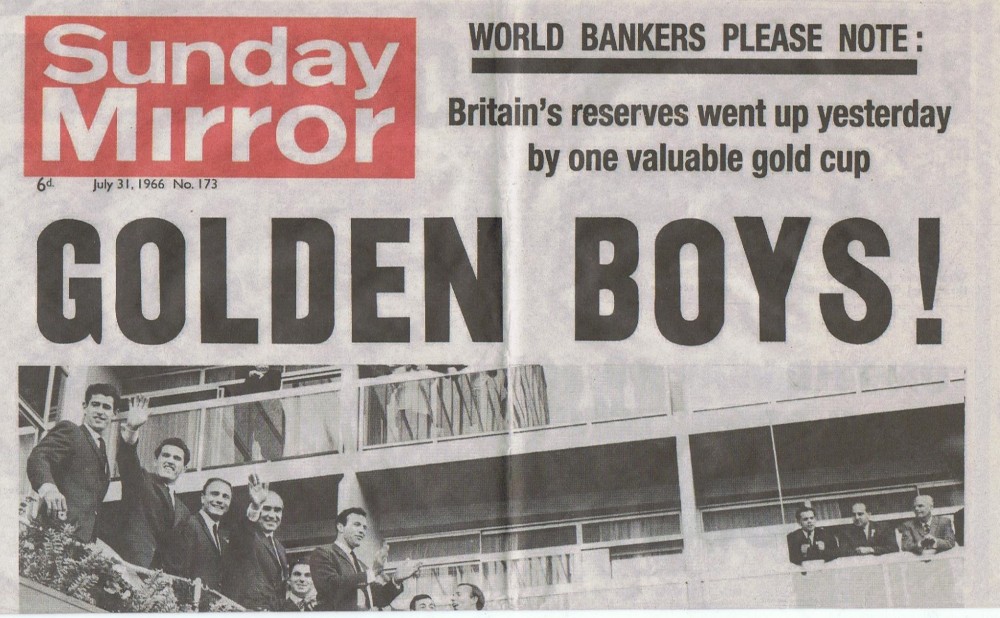

The policies of the Coalition government, the alleged sale of honours by Lloyd George, the Irish treaties of 1920 and 1921, the failures of the international conferences at Cannes and Genoa, and the Chanak incident of 1922 exacerbated the withdrawal of backbench Conservative support for the Coalition Government. That dissatisfaction came to a head for the Tories in October 1922 when Austen Chamberlain and Stanley Baldwin argued the cases for and against continuing the Coalition. Baldwin’s victory and the fall of the Coalition government led to Lloyd George and his Liberals being without positive programmes. The disastrous 1922 election was followed by a further fusion between the two wings of the Liberal Party and they revived in the 1923 General Election. But this was a short-lived triumph and in the 1924 election, the Liberals slumped to forty MPs, with less than eighteen per cent of the total vote. After this, the Liberals were a spent force in British politics.

At the famous meeting of ‘back-bench’ Conservative MPs at the Carlton Club on 19 October 1922, Chamberlain debated with Stanley Baldwin the future direction of their party in the following terms:

The real issue is not between Liberals and Conservatives. It is not between the old Liberal policy and the old Conservative policy. It is between those who stand for individual freedom and those who are for the socialisation of the State; those who stand for free industry and those who stand for nationalisation, with all its controls and inefficiencies.

Stanley Baldwin, acknowledging that Lloyd George was a dynamic force, a remarkable personality, but one which had already smashed the PM’s own party to pieces, and would go on to do the same to the Tory Party if they let it. Baldwin’s victory over Chamberlain and the fall of the Coalition left Lloyd George and his Liberals without partners and without positive programmes of their own. Lloyd George had become an electoral liability both the Conservatives and, as it soon turned out, even the Liberals could do without.

In the British political and electoral system, there was no place for two parties of the Right or two parties of the Left. This was the Liberal dilemma. By 1924, the Liberal-Conservative see-saw had been replaced by a fast-spinning roundabout of alternate governments of the Labour and Conservative parties on which there was little opportunity for the Liberals to jump on board. To change the metaphor completely, they now found themselves caught between the Devil and the deep blue sea. Where, then, did the Liberal support go? Liberal ideals were no longer as relevant to the twentieth century as they had been in Victorian and Edwardian times. In fact, both the Labour and Conservative parties benefited from the Liberal decline. Given that Conservative-led governments dominated Britain for all but three years of the 1918-39 period, the Liberal decline perhaps helped the Right rather than the Left. Besides which, the logic of the ‘adversarial’ British political system favoured a dominant two-party system rather than a multi-party governmental structure. Yet even the emergence of a working-class party with an overtly Socialist platform could not alter the fundamentals of a parliamentary politics based on the twin pillars of finding consensus and supporting capitalism. Despite his party’s commitment to Socialism, Ramsay MacDonald accepted the logic of this situation.

History has not been kind to the memories of either Stanley Baldwin or Ramsay MacDonald who dominated politics between 1922 and 1937. The first is still seen as the Prime Minister who thwarted both the General Strike and the rule of Edward VIII. The latter is seen, especially in his own party, as the great betrayer who chose to form a National Government in 1931, resulting in the split in that party. Here, I am concerned with the causes of that split and the motives for MacDonald’s actions. A further article will concern itself with the consequences of those actions and the split resulting in Labour’s biggest electoral disaster to date in 1935. In his book, published in 1968, The Downfall of the Liberal Party, 1914-1935, T. Wilson has pointed out the need for historians to take a long view of Liberal decline, going back to the 1880s and as far forward as 1945. In particular, he points to the fact that, in the three decades following 1914, the Conservatives held office almost continuously, with only two minor interruptions by Labour minority governments. In part, he suggested, this was the consequence in the overall decline of ‘the left’ in general, by which he seems to have meant the ‘left-liberals’ rather than simply the Socialists:

The left parties suffered from the loss of buoyancy and self-confidence which followed from Britain’s decline as a world power and the experiences of the First World War, as well as from the twin phenomena of economic growth and economic crisis which ran parallel after 1914. The resultant urge to play safe proved largely to the advantage of the Conservatives. So did the decline in ‘idealism’. … Before 1914 the Liberal and Labour parties so managed their electoral affairs that between them they derived the maximum advantage from votes cast against the Conservatives. After 1914 this became impossible. During the First World War Labour became convinced – and the decrepit state of Liberalism even by 1918 deemed to justify this conviction – that the Liberal Party would soon be extinguished altogether and that Labour would appropriate its entire following. … By concentrating on destroying the Liberals, Labour was ensuring its own victory “in the long run”, even though in the short run the Conservatives benefited. …

Certainly, from 1918 to 1939 British politics was dominated by the Conservative Party. Either as a dominant member of a Coalition or National government or as a majority government, the Conservative Party retained hegemony over the system.

Structural Decline – The State of the ‘Staple’ Industries:

The problems which British politicians faced in the inter-war period were primarily of an economic nature. British industry was structurally weak and uncompetitive. It was therefore not surprising that two areas were of particular concern to politicians: first, the state of the staple industry, especially coal with its immense workforce; and secondly, the question of unemployment benefits and allowances.

Above: A boy working underground with his pity pony. In 1921, the school-leaving age was fourteen, though many left in the spring before their fourteenth birthday and boys were legally allowed to work underground in mines at this age, entering the most dangerous industrial occupation in the country.

Pictures can create an impression of mining life but they cannot convey the horrific danger of the work, and even the statistics elude the experience. Every five hours a miner was killed and every ten minutes five more were maimed. Every working day, 850 suffered some kind of serious injury. In the three years, 1922-24, nearly six hundred thousand were injured badly enough to be off work for seven days or more. No records were kept of those of work for fewer than seven days. Combined with work that was physically destructive over a longer period, producing diseases such as pneumoconiosis and silicosis were working conditions that are virtually indescribable and company-owned housing that was some of the worst in Britain. The reward for the daily risk to health and life varied from eight to ten shillings and ninepence a day according to the ‘district’ from eight shillings and fivepence a day in South Staffordshire to ten shillings and ninepence in South Wales. That was the wage the owners insisted on cutting and the toil they insisted on lengthening. The mine-owners were joined together in a powerful employers’ organisation known as the Mining Association. They represented owners like Lord Londonderry, the Duke of Northumberland and Lord Gainford, men whose interests extended to banking and press proprietorship. They also spoke for big landowners like the Duke of Hamilton and Lord Bate who drew royalties on every shovelful of coal hacked from beneath their lands, amounting to more than a hundred thousand pounds a year.

In 1915, the MFGB had formed a ‘Triple Industrial Alliance’ with the National Union of Railwaymen and the Transport Workers’ Federation. Its joint executive could order combined action to defend any of the three unions involved in a dispute. However, the Alliance ended on 15 April 1921 which became known as ‘Black Friday’. The NUR, the Transport Workers’ Federation, the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Fireman called off their strike, leaving the Miners to fight on. All along the Miners had said they were prepared to make a temporary arrangement about wages, provided that the principle of a National Wages Board was conceded. On the eve of ‘Black Friday’, the Miners’ leader, Frank Hodges suggested that they would be prepared to accept a temporary wage arrangement, provided it did not prejudice the ultimate decision about the NWB, thus postponing the question of the Board until after the negotiations. It was this adjustment that stopped the strike and ended the Alliance. The Daily Herald, very much the ‘mouthpiece’ for Labour, reported the following morning:

Yesterday was the heaviest defeat that has befallen the Labour Movement within the memory of man.

It is no use trying to minimise it. It is no use trying to pretend it is other than it is.We on this paper have said throughout that if the organised workers would stand together they would win. They have not stood together, and they have been broken. It is no use for anyone to criticise anyone else or to pretend that he himself would have done better than those have done who have borne the heaviest responsibility. …

The owners and the Government have delivered a smashing frontal attack upon the workers’ standard of life. They have resolved that the workers shall starve, and the workers have not been sufficiently united to stand up to that attack.

The Triple Alliance, the Trades Union Congress, the General Staff, have all failed to function. We must start afresh and get a machine that will function.

… We may be beaten temporarily; it will be our own fault if we are not very soon victorious. Sectionalism is the waekness of the movement. It must be given up. Everybody must come back to fight undiscouraged, unhumiliated, more determined than ever for self-sacrifice, for hard-work, and for solidarity. … We must concentrate on the Cause.

The thing we are fighting for is much too big to be beaten by Mr Lloyd George or by anything except betrayal in our own ranks and in our own hearts.

Already by 1922, forty-three per cent of Jarrow’s employable persons were out of work, whilst forty-seven per cent in Brynmawr and sixty per cent in Hartlepool were in the same condition. By contrast with the unforgiving bitterness of class war across mainland Europe, however, social divisions in Britain were mitigated by four main ‘cultural’ factors; a common ‘heritage’; reverence for the monarchy; a common religion, albeit divided between Anglican, Nonconformist and Catholic denominations; an instinctive enjoyment of sport and a shared sense of humour. All four of these factors were evident in the class-based conflicts of 1919-26. In March 1922, the Daily News reported that an ex-soldier of the Royal Field Artillery was living with his wife and four children in London under a patchwork shack of tarpaulins, old army groundsheets and bits of tin and canvas. He told the reporter:

If they’d told in France that I should come back to this I wouldn’t have believed it. Sometimes I wished to God the Germans had knocked me out.

In the House of Commons in June 1923, the ILP MP James (‘Jimmy’) Maxwell used his ‘privileges’ to accuse the Baldwin government and industrialists of ‘murder’:

In the interests of economy they condemned hundreds of children to death, and I call it murder … It is a fearful thing for any man to have on his soul – a cold, callous, deliberate crime in order to save money. We are prepared to destroy children in the great interest of dividends. We put children out in the front of the firing line.

Baldwin & MacDonald arrive ‘centre-stage’:

In attempting to remedy the existing state of affairs, Baldwin set himself a dual-task. In the first place, he had to lead the Conservatives to some imaginative understanding of the situation which had called a Labour Party into being and to convince them that their survival depended on finding a better practical solution to the problems than Labour’s. Secondly, he sought to convince potential Labour voters that not all Conservatives were blood-sucking capitalists, that humanity and idealism were not the exclusive prerogatives of left-wing thinkers. For the cartoonists and the and the public at large, there was Baldwin’s carefully cultivated image of the bowler hat and the pipe, Sunday walks in the Worcestershire countryside which ended in the contemplation of his pigs; ‘Squire Baldwin’ appeared, according to William McElwee, to be simple, straightforward, homely and above all trustworthy. MacDonald had the same task in reverse. He had to convince the nation that Labour was a responsible party, perfectly competent to take over the reins of government, and resolved to achieve in its programme of reforms within the framework of the constitution. He had also to persuade Labour itself that it was in and through Parliament that social progress could best be achieved; that the existing constitutional structure was not designed to shore up capitalism and preserve personal privilege, but was available for any party to take hold of and will the means according to its declared ends, provided it could ensure a democratically elected majority.

Both Baldwin and MacDonald were enigmatic figures to contemporaries and still are today. On Baldwin, one contemporary commented in 1926 that …

If on the memorable afternoon of August 3, 1914, anyone, looking down on the crowded benches of the House of Commons, had sought to pick out the man who would be at the helm when the storm that was about to engulf Europe was over he would not have given a thought to the member for Bewdley. … He passed for a typical backbencher, who voted as he was expected to vote and went home to dinner. A plain, undemonstrative Englishman, prosperous and unambitious, with a pleasant, humorous face, bright and rather bubolic colouring, walking with a quick, long stride that suggested one accustomed to tramping much over ploughed fields with a gun under his arm, and smoking a pipe with unremitting enjoyment. …

McElwee considers their personality traits in his book, Britain’s Locust Years, in which he tries to indicate the immensity of the problem facing these problems, characterising it as years of plenty followed by years of shortage. He raises the important question of judgement and argues that the historian must reach a ‘truer perspective’ in appreciating that the problems facing the country in 1925 were very different from those which had to be confronted in 1935 and 1945. Yet the picture still emerges in the national mind of…

… Baldwin personified by his pipe and pigs and MacDonald by his vanity, ambition and betrayal.

This popular picture, he suggests, fails to take into account the contribution each made to his own party. Both men could claim that during their periods in office they were compelled to act in ‘the national interest’. The events of 1926, in the case of Baldwin, and 1931, in the case of MacDonald, and their actions in them, could both be justified on these grounds alongside the judgements they made. Historians’ interpretations of these judgements must depend first on the available evidence and secondly on their analysis and treatment of this evidence-based on non-partisan criteria. Only then can they adduce true motives. As for the Liberals, the disastrous 1922 election was followed by a re-fusion between the two wings of the Liberal Party and they revived their fortunes somewhat in the 1923 General Election. But this was a short-lived recovery and in the 1924 election, they slumped to forty MPs, with only 17.6 per cent of the total vote. Their decline after 1924 can be seen in the electoral statistics below:

Table I: General Election Results, 1918-1929.

Table II: Liberals and the General Elections, 1918-1929.

Writing in Certain People of Importance in 1926, A. G. Gardiner suggested that the emergence of Mr Baldwin would furnish the historian with an attractive theme. … The ‘Diehards’, following the fateful Carlton Club Meeting, at which he effectively broke up the Coalition, felt that at last, they had found a hero. But in November 1923 Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative Government fell. In 1923, in the middle of the election campaign, a Cabinet colleague was asked to explain the true inwardness of his leader’s sudden and inexplicable plunge into Protection, he replied: Baldwin turned the tap on and then found that he could not turn it off. Gardiner commented by extending this metaphor:

He is always turning taps on and then found that he does not know how to stop them. And when the bath overflows outside, lights his pipe, and rejoices that he has such a fine head of water on his premises. …

The Tory’s revival of ‘Protectionism’ was an attempt to stem the tide of support for Labour by protecting the new engineering jobs which were growing rapidly in the new industrial areas of the Midlands, which were meeting the demand for new electrical goods in the home market. My own grandparents, a miner and silk-weaver campaigning for Labour from the front room of their new semi-detached house in Coventry, which served as the Party’s constituency office, used to sing the following campaign song decades later, to the tune of ‘Men of Harlech’:

Voters all of Aberavon!

Wisdom show in this election,

Don’t be misled by Protection,

Ramsay is yer man.

Ramsay, Ramsay! Shout it!

Don’t be shy about it!

On then comrades, on to glory!

It shall be told in song and story,

How we beat both Lib and Tory!

Ramsay is yer man!

In the following month’s general election (the full results of which are shown in the statistics in Table I above), the Labour Party won 191 seats to the Conservatives’ 258 and the Liberals’ 158; Margaret Bondfield was elected in Northampton with a majority of 4,306 over her Conservative opponent. She had been elected to the TUC Council in 1918 and became its chairman in 1923, shortly before she was first elected to parliament. In an outburst of local celebration her supporters, whom she described as “nearly crazy with joy”, paraded her around the town in a charabanc. She was one of the first three women—Susan Lawrence and Dorothy Jewson (pictured in the group photo below) were the others—to be elected as Labour MPs. With no party in possession of a parliamentary majority, the make-up of the next government was in doubt for some weeks until Parliament returned after the Christmas ‘recess’.

In the short-lived minority Labour government of 1924, Margaret Bondfield, seen above as Chairman of the TUC, served as parliamentary secretary in the Ministry of Labour.

The First Labour Government:

The Liberal Party’s decision not to enter a coalition with the Conservatives, and Baldwin’s unwillingness to govern without a majority, led to Ramsay MacDonald’s first minority Labour government which took office in January 1924.

The Women MPs elected to Parliament in 1923 (three were Labour)

Working-class expectations of the First Labour government were soaring high, despite its ‘absolute’ minority status and the lack of experience of its cabinet ministers. Beatrice Webb wrote in her diaries (1924-32) for 8th January:

I had hoped to have the time and the brains to give some account of the birth of the Labour Cabinet. There was a pre-natal scene – the Embryo Cabinet – in JRM’s room on Monday afternoon immediately after the defeat of the Government when the whole of the prospective Ministers were summoned to meet the future PM (who) … did not arrive until half an hour after the time – so they all chatted and introduced themselves to each other. … On Tuesday (in the first week of January), JRM submitted to the King the twenty members of the Cabinet and there was a formal meeting at 10 Downing Street that afternoon of the Ministers designate. Haldane gave useful advice about procedure: Wheatley and Tom Shaw orated somewhat, but for the most part the members were silent, and what remarks were made were businesslike. The consultation concerned the PM’s statement to Parliament. …

On Wednesday the twenty Ministers designate, in their best suits … went to Buckingham Palace to be sworn in; having been previously drilled by Hankey. Four of them came back to our weekly MP’s lunch to to meet the Swedish Minister – a great pal of ours. Uncle Arthur (Henderson) was bursting with childish joy over his H. O. seals in the red leather box which he handed round the company; Sidney was chuckling over a hitch in the solemn ceremony in which he had been right and Hankey wrong; they were all laughing over Wheatley – the revolutionary – going down on both knees and actually kissing the King’s hand; and C. P. Trevelyan was remarking that the King seemed quite incapable of saying two words to his new ministers: ‘he went through the ceremony like an automation!’

J. R. Clynes, the ex-mill-hand, Minister in the Labour Government, recalled their sense of being ‘out of place’ at the Palace:

As we stood waiting for His Majesty, amid the gold and crimson of the Palace, I could not help marvelling at the strange turn of Fortune’s wheel, which had brought MacDonald, the starveling clerk, Thomas the engine-driver, Henderson the foundry labourer and Clynes, the mill-hand to the pinnacle.

The pictures and captions above and elsewhere in this article are taken from ‘These Tremendous Years, 1918-38’, published c.1939, a ‘picture-post’ -style publication. What is interesting about this report is its references to the King’s attitude, which contrasts with that reported by Beatrice Webb, and to the Labour Ministers as ‘the Socialists’.

According to Lansbury’s biographer, Margaret Bondfield turned down the offer of a cabinet post; instead, she became parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Labour, Tom Shaw. This appointment meant that she had to give up the TUC Council chair; her decision to do so, immediately after becoming the first woman to achieve this honour, generated some criticism from other trade unionists. She later described her first months in government as “a strange adventure”. The difficulties of the economic situation would have created problems for the most experienced of governments, and the fledgeling Labour administration was quickly in difficulties. Bondfield spent much of her time abroad; in the autumn she travelled to Canada as the head of a delegation examining the problems of British immigrants, especially as related to the welfare of young children. When she returned to Britain in early October 1924, she found her government already in its final throes. On 8 October MacDonald resigned after losing a confidence vote in the House of Commons. Labour’s chances of victory in the ensuing general election were fatally compromised by the controversy surrounding the so-called Zinoviev letter, a missive purportedly sent by Grigory Zinoviev, president of the Communist International, which called on Britain’s Socialists to prepare for violent revolution:

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE, THIRD COMMUNIST

INTERNATIONAL PRESIDIUM.

MOSCOW

September 15th 1924

To the Central Committee, British Communist Party.

DEAR COMRADES,

The time is approaching for the Parliament of England to consider the Treaty concluded between the Governments of Great Britain and the SSSR for the purpose of ratification. The fierce campaign raised by the British bourgeoisie around the question shows that the majority of the same … (is) against the Treaty.

It is indispensible to stir up the masses of the British proletariat, to bring into movement the army of unemployed proletarians. … It is imperative that the Labour Party sympathising with the Treaty should bring increased pressure to bear upon the Government and Parliament any circles in favour of ratification …

… A settlement of relations between the two countries will assist in the revolutionising of the international and British Proletariat not less than a successful rising in any of the working districts of England, as the establishment of close contact between the British and Russian proletariat, … will make it possible for us to extend and develop the propaganda and ideals of Leninism in England and the Colonies. …

From your last report it is evident that agitation propaganda in the Army is weak, in the Navy a very little better … it would be desirable to have cells in all the units of troops, particularly among those those quartered in the large centres of the Country, and also among factories working on munitions and at military store depots. …

With Communist greetings,

ZINOVIEV

President of the Presidium of the I.K.K.I.

McMANUS

Member of the Presidium

KUUSINEN

Secretary

Pictured right: The Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald, depicted in a hostile Punch cartoon. The luggage label, marked “Petrograd”, links him to Russia and communism.

Pictured right: The Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald, depicted in a hostile Punch cartoon. The luggage label, marked “Petrograd”, links him to Russia and communism.

The letter, published four days before polling day, generated a “Red Scare” that led to a significant swing of voters to the right, ensuring a massive Tory victory (Table I).

Margaret Bondfield lost her seat in Northampton by 971 votes. The scare demonstrated the vulnerability of the Labour Party to accusations of Communist influence and infiltration.

The Conservatives & the Coal Crisis – Class War?

Baldwin (pictured on the left above) and his Tories were duly returned to power, including Winston Churchill as Chancellor of the Exchequer. It was Churchill’s decision in 1925 to return Britain to the Gold Standard, abandoned in 1914, together with his hard-line anti-unionism displayed during the General Strike, for which his second period in office is best remembered. The decision was a monetary disaster that hit the lowest paid hardest since it devalued wages dramatically. Despite being flatly warned by the Cambridge economist Hubert Henderson that a return to gold… cannot be achieved without terrible risk of renewed trade depression and serious aggravation and of unemployment, it was actually Baldwin who told Churchill that it was the Government’s decision to do so. Churchill decided to go along with Baldwin and the Bank of England, which restored its authority over the treasury by the change. The effect of the return to the Gold Standard in 1926, as predicted by Keynes and other economists, was to make the goods and services of the most labour-intensive industries even less competitive in export markets. Prices and the numbers out of work shot up, and wages fell. In the worst-affected industries, like coal-mining and shipbuilding, unemployment was already approaching thirty per cent. In some places in the North, it reached nearly half the insured workforce. In the picture on the right above, miners are anxiously reading the news about the ‘Coal Crisis’.

Beatrice Webb first met the ‘Billy Sunday’ of the Labour Movement, as Cook was nicknamed, with George Lansbury. He was the son of a soldier, born and brought up in the barracks, then a farm-boy in Somerset when he migrated, like many others, to the booming South Wales coalfield before the First World War, a fact which was continually referred to by the Welsh-speaking Liberal élite in the Social Service movement. He had, however, passed through a fervent religious stage at the time of the great Welsh Revival, which he came out of by coming under the influence of the ‘Marxist’ Central Labour College and Noah Ablett, whom he helped to write The Miners’ Next Step, a Syndicalist programme for workers’ control of the coal industry, published in 1912. Graduating into Trade Union politics as a conscientious objector and avowed admirer of Lenin’s, he retained the look of the West country agricultural labour, with china-blue eyes and lanky yellow hair, rather than that of the ‘old Welsh collier’ so admired by the Liberals. For Webb, however, Cook was altogether a man you watch with a certain curiosity, though to her husband, Sidney, who was on the Labour Party Executive, he was rude and unpleasing in manner. However, Beatrice also judged that…

It is clear that he has no intellect and not much intelligence … an inspired idiot, drunk with his own words, dominated by his own slogans. I doubt whether he knows what he is going to say or what he has just said. It is tragic to think that this inspired idiot, coupled with poor old Herbert Smith, with his senile obstinacy, are the dominating figures in so great and powerful an organisation as the Miners’ Federation.

Walter Citrine, the TUC General Secretary in 1926, had a similarly mixed view of Cook’s speaking abilities:

In speaking, whether in private or public, he never seemed to finish his sentences. His brain raced ahead of his words. He would start out to demonstrate something or other in a logical way … but almost immediately some thought came into his mind and he completely forgot all about (his main theme) and never returned to it. He was extremely emotional and even in private conversation I have seen tears in his eyes.

The mine owners’ response to the crisis, made worse by the fact that the German minefields were back in production, was to demand wage cuts and extensions to working hours. Worried about the real possibility of a general strike, based on the Triple Alliance between the miners, dockers and railwaymen, Baldwin bribed the owners with government subsidies to postpone action until a royal commission could report on the overall problems of the industry. However, when the Samuel Commission reported in March 1926, its first of seven recommendations was a cut in wages. The response of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, voiced by their militant national secretary, A. J. Cook, was to set out the miner’s case in emotive terms:

Our case is simple. We ask for safety and economic security. Today up and down the coalfields the miner and his family are faced with sheer starvation. He is desperate. He will not, he cannot stand present conditions much longer. He would be a traitor to his wife and children if he did. Until he is given safety in mines, adequate compensation, hours of labour that do not make him a mere coal-getting medium, and decent living conditions, there can be no peace in the British coalfields.

Lord Birkenhead said that he thought the miners’ leaders the stupidest men he had ever met until he met the mine owners. They proved him right by locking the miners out of the pits at midnight on 30 April. The Mining Association, strongly supported by Baldwin and Churchill, stated that the mines would be closed to all those who did not accept the new conditions from 2 May 1926. The message from the owners was clear; they refused to meet with the miners’ representatives and declared that they would never again submit to national agreements but would insist on district agreements to break the power and unity of the MFGB and force down the living standards of the miners to an even lower level. The smallest reduction would be imposed on mine labourers in Scotland, eightpence farthing a day, the largest on hewers in Durham, three shillings and eightpence a day. Cook responded by declaring:

We are going to be slaves no longer and our men will starve before they accept a reduction in wages.

Above: Women and children queue outside the soup kitchen in Rotherham, Yorkshire, during the miners’ lock-out in 1926.

The Nine Days of the General Strike:

The following day, Saturday 1 May, the TUC special Conference of Executive Committees met in London and voted to call a General Strike in support of the miners by 3,653,527 votes to just under fifty thousand. As early as 26 February, the TUC had reiterated support for the miners, declaring there was to be no reduction in wages, no increase in working hours, and no interference with the principle of national agreements. In the face of the impending lockout, the special Conference had begun meeting at Farringdon Street on 29 April and continued in session until 1 May. At this conference, in a committed and passionate speech, Bevin said of the decision to strike in support of the miners …

… if every penny goes, if every asset goes, history will ultimately write up that it was a magnificent generation that was prepared to do it rather than see the miners driven down like slaves.

The TUC Memorandum called for the following trades to cease work as an when required by the General Council:

Transport, … Printing Trades including the Press, … Productive Industries, Iron and Steel, Metal, and Heavy Chemical, … Building Trade, … Electricity and Gas, … Sanitary Services, … but … With regard to hospitals, clinics, convalescent homes, sanatoria, infant welfare centres, maternity homes, nursing homes, schools … affiliated Unions (were) to take every opportunity to ensure that food, milk, medical and surgical supplies shall be efficiently provided. Also, there was to be no interference in regard to … the distribution of milk and food to the whole of the population.

Telegrams were sent out on 3 May and on the 4th more than three million workers came out on strike. The General Council issued a further statement that evening, again placing the responsibility for the ‘national crisis’ on the shoulders of the Government. It went on to try to reassure the general population of its good intentions in calling the strike:

With the people the trade unions have no quarrel. On the contrary, the unions are fighting to maintain the standard of life of the great mass of people.

The trade unions have not entered upon this struggle without counting the cost. They are assured that the trade unionists of the country, realising the justice of the cause they are called upon to support, will stand loyally by their elected leaders until the victory and an honourable peace has been won.

The need now is for loyalty, steadfastness and unity.

The General Council of the Trade Union Congress appeals to the workers to follow the instructions that have been issued by their union leaders.

Let none be disturbed by rumours or driven by panic to betray the cause.

Violence and disorder must be everywhere avoided no matter what the cause.

Stand firm and we shall win.

On the 4th, The Daily Herald published the following editorial backing the Strike:

The miners are locked out to enforce reductions of wages and an increase in hours. The Government stands behind the mineowners. It has rebuffed the Trade Union Movement’s every effort to pave the way to an honourable peace.

The renewed conversations begun on Saturday were ended abruptly in the early hours of yesterday morning, with an ultimatum from the Cabinet. Despite this, the whole Labour Movement, including the miners’ leaders, continued its efforts yesterday.

But unless a last minute change of front by the Government takes place during the night the country will today be forced, owing to the action of the Government, into an industrial struggle bigger than this country has yet seen.

In the Commons Mr Baldwin showed no sign of any receding from his attitude that negotiations could not be entered into if the General Strike order stood and unless reductions were accepted before negotiations opened.

In reply Mr J. H. Thomas declared that the responsibility for the deadlock lay with the Government and the owners, and that the Labour Movement was bound in honour to support the miners in the attacks on their standard of life.

In the following eight days, it was left to local trades unionists to form Councils of Action to control the movement of goods, disseminate information to counter government propaganda, to arrange strike payments and to organise demonstrations and activities in support of the strike. The scene in the photo above gives a strong impression of the life of a northern mining community during the strike, in which a local agitator harangues his audience, men and children in clogs, with flat caps and pigeon baskets. Most of the photographs of 1926 taken by trades unionists and Labour activists do not show the strike itself but reveal aspects of the long lone fight of the miners to survive the lock-out. We know from the written and oral sources that the nine days in May were sunny and warm across much of the country, perfect for outside communal activities. The Cardiff Strike Committee issued the following advice:

Keep smiling! Refuse to be provoked. Get into your garden. Look after the wife and kiddies. If you have not got a garden, get into the country, the parks and the playgrounds.

At Methil, in Scotland, the trades unionists reacted to the call in a highly organised manner, the Trades and Labour Council forming itself into a Council of Action with sub-committees for food and transport, information and propaganda and mobilising three cars, one hundred motorcycles and countless bicycles for its courier service. Speakers were sent out in threes, a miner, a railwayman and a docker to emphasise the spirit of unity with the miners. Later in the strike, the Council of Action added an entertainments committee and, more seriously, a Workers’ Defence Corps after some savage baton charges by the police upon the pickets. The snapshots are from Methil, one showing miners and their families waiting to hear speeches from local leaders, one man holding a bugle used to summon people from their homes. The lower photo shows three pickets arrested during disturbances at Muiredge. Deploying a sense of humour reminiscent of that of the class-conscious ‘Tommies’ in the trenches, the Kensington strike bulletin greeted Sir John Simon’s pronouncement on the legality of the Strike with the following sardonic comment:

Sir John Simon says the General Strike is illegal under an Act passed by William the Conqueror in 1066. All strikers are liable to be interned in Wormwood Scrubs. The three million strikers are advised to keep in hiding, preferably in the park behind Bangor Street, where they will not be discovered.

Throughout the country, those called upon by the TUC to stop work did so with enthusiasm and solidarity. The photograph of trades unionists marching through ‘well-heeled’ Leamington Spa (above) is typical of thousands of similar popular demonstrations of solidarity that took place throughout Britain. Though the establishment in general and Winston Churchill, in particular, feared revolution, the march of building workers and railwaymen has the air of a nineteenth-century trade union procession, like those led by Joseph Arch in the surrounding Warwickshire countryside, the carpenters and joiners parading examples of their work, window sashes and door frames, through the streets on the back of a horse-drawn wagon. The figure in the foreground, marked with an x, is E Horley, a member of the Bricklayers’ Union. It was a scene repeated in a thousand towns as meetings were held, trade union news sheets were printed daily, and Councils of Action controlled the movement of supplies, organised pickets (Bolton organised 2,280 pickets in two days) and provided entertainment and speakers.

Government plans to cope with the strike of the ‘Triple Alliance’ or for a general strike had originated in 1919. The TUC seemed unaware of the government plans to distribute supplies by road though Lloyd George claimed that Ramsay MacDonald was aware of it and even prepared to make use of it during 1924. The organisation had evolved steadily during a period of continued industrial arrest and was accelerated after ‘Red Friday’ in 1925 so that the government was not only ready to take on the miners but was looking forward to dealing the unions a massive blow. Private support for a strikebreaking force came from a body calling itself the ‘Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies’ (OMS) under ‘top brass’ military leadership. The professional classes hastened to enrol, especially those with military commissions and experience, alongside industrialists.

Whilst the popular image of the Strike is one of the ‘Oxbridge’ undergraduates driving buses, the reality was that most of the strike-breakers were as working-class as the strikers. Churchill, however, mobilised resources as if he were fighting a war. Troops delivered food supplies; he set up the British Gazette and ran it as a government propaganda sheet (above), with more soldiers guarding the printing presses.

The armed forces were strategically stationed, armoured cars and tanks brought out for guard and escort duties. The Riot Act was read to the troops and even the artillerymen were given bayonet drill. Both food deliveries and Gazette deliveries were sometimes accompanied by tanks. Attempts to press Lord Reith’s BBC, which had begun broadcasting in 1922, to put out government bulletins, were defiantly resisted, a turning point in the fight for the corporation’s political independence.

The photograph above shows troops carrying an ammunition box into their temporary quarters at the Tower of London, where the contents of London’s gunshops were also stored during the strike.

Since 1925, the number of special constables had been increased from 98,000 to 226,000 and a special reserve was also created. This numbered fifty thousand during the strike by ‘reliable’ volunteers from the universities, the professions and by retired army officers who happily donned the blue and white armband over cricket sweaters and drew their helmets from the government stores. The photo above shows a group of swaggering polo-playing ex-officers wielding yard-long clubs and flourishing whips replete with jodhpurs. They cantered around Hyde Park in military formation. The class divisions were clearly drawn and while for the most part, the volunteers saw it as answering a patriotic call, some talked of ‘teaching the blighters a lesson’.

In a strike remarkable for a lack of violence, given all the ingredients for near civil war, it was the specials who were involved in some of the most brutal incidents during the nine days. The most dramatic incident was the semi-accidental derailment of The Flying Scotsman by a group of miners from Cramlington Lodge, but their four-hundred-yard warning enabled the engine to slow to twenty m.p.h. before it toppled off the section where they had removed a rail. Consequently, no-one was hurt, but a police investigation led to one of the miners turning King’s Evidence and his nine ‘comrades’ were arrested and given sentences of four, six and eight year’s penal servitude. On the other side, mounted specials supported the Black and Tans in an unprovoked attack on a mixed crowd in Lewes Road, Brighton, while at Bridgeton attacks by the specials on unoffending citizens led to an official protest by the Glasgow Town Council Labour Group. It was also the specials who took part in raids on trade union offices and arrested workers for selling strike bulletins; for the miners, it was a fight for survival, for the university students and their middle-aged fathers in search of glory, it was all ‘jolly good fun’.

At the height of the strike, with messages of support pouring into the TUC, the number of strikers growing and spirits high, the strike was suddenly brought to an end on 12 May. At first, trade union officials announced it as a victory, for example at a mass meeting at Gravesend. With the strike solid and growing daily and trades unions in control of many areas, its ending was similarly interpreted in hundreds of cities, towns and villages throughout the country. As the truth slowly became known, the news was received with shock and disbelief. The strike had lasted just nine days before it was called off unconditionally by the TUC General Council. The coalowners and the Conservatives had no doubt at all that it was an unconditional surrender. Certainly, J. H. Thomas’ announcement of the end of the strike seemed to one group of railwaymen listening to the ‘wireless’ to confirm this:

We heard Jimmy Thomas almost crying as he announced the terms of what we thought were surrender, and we went back with our tails between our legs to see what the bosses were going to do with us.

The next day The Daily Mail headline was ‘surrender of the revolutionaries’ and Churchill’s British Gazette led with ‘Surrender received by Premier’. The TUC had agreed to the compromise put forward by the Samuel Commission, but the embittered MFGB leadership did not and the lock-out continued for seven months (see the photo below, titled End of the Strike). The miners refused to accept the cut in wages and increase in hours demanded by the owners and the government.

The reasoning behind this decision has been argued over ever since, but, following the backlash over the ‘Zinoviev Letter’, the General Strike of 1926 demonstrated the unwillingness of even radical trade unionists to push the system too far and be seen to be acting coercively and unconstitutionally. Additionally, when the showdown came in 1926 it was not really, as The Times had dramatised it in September 1919, a fight to the finish, because industrial union power was already shifting to other sections of the economy.

From Retribution & Recrimination to ‘Recovery’ & Reconciliation, 1926-29:

After the Strike was called off, the bitter polarisation of the classes remained. There are few photographs which record the misery of victimisation that followed the ending of the strike. Courageous men in lonely country districts who had struck in twos and threes were easy victims for retribution. The railway companies were the first to act we, turning away railwaymen when they reported for work. Men with decades of loyal service were demoted, moved to posts far from home, or simply not re-engaged. The railwayman quoted above was one of these victims:

I was told within a couple of days that I had been dismissed the service – a very unusual thing, and I think that very few station masters in the Kingdom can say that they had had the sack, but that was the case with me, and I know at least two more who had the same experience.

Of those who formed the TUC deputation to Baldwin, only Ernest Bevin sought an assurance against retribution. None was given, so speaking at the end of the strike, he prophesied that thousands would be victimised as a result of this day’s work. The NUR was forced to sign a humiliating document that included the words the trade unions admit that in calling the strike they committed a wrongful act. The coalowners’ final reckoning came with the slow return to work at the end of the year. They prepared blacklists, excluding ‘militants’ from their pits, and gave them to the police at the pitheads. Some men never returned to work until 1939, following Britain’s declaration of war. Vengeful employers felt justified in these actions by the blessings they had received from the pulpits of Christian leaders, including Cardinal Bourne, the Roman Catholic Primate and Archbishop of Westminster, preaching in Westminster Cathedral on 9th May:

There is no moral justification for a General Strike of this character. It is therefore a sin against the obedience which we owe to God. … All are bound to uphold and assist the Government, which is the lawfully-constituted authority of the country and represents therefore, in its own appointed sphere, the authority of God himself.

In a period when these issues of morality, legitimacy, and constitutionalism carried great weight, and church-going was still significant among all classes, it is not wholly surprising that the TUC leaders were wary of over-reaching their power in mid-twenties’ Britain. We also need to recall that the Labour Party had a very strong tradition of pacifism, and although outbreaks of violence against people or property were rare events during the coal stoppage and the General Strike, at the time the strike was called off there would have been natural concerns among the Labour leaders about their ability to control the more militant socialists and communists active among the rank and file trades unionists. George Lansbury (pictured below) addressed some of these concerns in the context of his Christian Socialism:

One Whose life I revere and Who, I believe, is the greatest Figure in history, has put it on record: “Those who take the sword shall perish by the sword” … If mine was the only voice in this Conference, I would say in the name of the faith I hold, the belief I have that God intended us to live peaceably and quietly with one another, if some people do not allow us to do so, I am ready to stand as the early Christians did, and say, “This is our faith, this is where we stand and, if necessary, this is where we will die.”

On the other hand, the Fabian Socialist, Beatrice Webb was scathing in her assessment of what she believed the General Strike had revealed about the lack of support for revolutionary socialism among British workers:

The government has gained immense prestige in the world and the British Labour movement has made itself ridiculous. A strike which opens with a football match between police and strikers and ends nine days later with densely-packed reconciliation services at all the chapels and churches of Great Britain attended by the strikers and their families, will make the continental Socialists blaspheme. Without a shot fired or a life lost … the General Strike of 1926 has by its absurdity made the Black Friday of 1921 seem to be a red letter day of common sense. Let me add that the failure of the General Strike shows what a ‘sane’ people the British are. If only our revolutionaries would realise the hopelessness of their attempt to turn the British workman into a Red Russian …The British are hopelessly good-natured and common-sensical – to which the British workman adds pigheadedness, jealousy and stupidity. … We are all of us just good-natured stupid folk.

The Conservative government revelled in the defeat of the strike and turned to the slow crushing of the miners. They sent an official note of protest to the Soviet government, determined to stop the collection of relief money by Russian trade unionists. Neville Chamberlain instructed the authorities to tighten up on relief payments which were already at a starvation figure of five shillings for a wife and two shillings for each child. The men were precluded from Poor Relief by a law originating in 1898 in which the coalowners had brought a court action against the Guardians of Merthyr Tydfil for giving miners outdoor relief during the miners’ strike of that year. The government was now quick to insist that work was available, albeit for longer hours and less pay than that those set out in the previous agreements between the mine-owners and the mineworkers, and then insisted that the law concerning relief should be vigorously applied, even to the pit boys, aged fourteen to sixteen, who were not allowed to join a trade union. When, after months of hunger and deprivation, the miners organised a fund-raising mission to the United States, Baldwin wrote a vindictive letter to the US authorities stating that there was no dire need in the coalfields. This was at a time when Will John, MP for Rhondda West, was telling the Board of Guardians that women were now carrying their children to the communal kitchens because the children had no shoes. As the plight of the miners grew worse, the govern In July, his government announced that a bill would be passed lengthening the working day in the mines.

Four million British subjects were thus put on the rack of hunger by a Cabinet of wealthy men. They even introduced a special new law, the Board of Guardians (Default) Bill, in an attempt to rule by hunger. Despite all these measures, the miners were able to exist for nearly seven months before being driven to accept the terms of the owners. This was a story of community struggle in the face of siege conditions. Aid for the miners came from the organised Labour and trade union movement, which raised tens of thousands of pounds. Russian trade unionists collected over a million pounds. Co-ops extended credit in the form of food vouchers, gave away free bread and made long-term loans. The funds of the Miners’ Federations and the MFGB proved hopelessly inadequate in supporting the ‘striking’ men.

Meanwhile, whilst the participants in round-table talks between the unions and management, convened by the chemical industrialist Sir Alfred Mond, were meant to reintroduce a spirit of goodwill into industrial relations, the Conservative government introduced a bill to prevent any future General Strike and attempted to sever the financial link between the unions and the Labour Party. This eventually became the 1927 Trade Disputes Act made it illegal for any strike to intend to coerce the government. It also became illegal for a worker in ‘essential employment’ to commit a breach of contract; in effect, this was a return to the old law of ‘master and servant’ which had been swept away by the Employers’ and Workmen’s Act of 1875.

Unemployed miners getting coal from the Tredegar ‘patches’ in the late twenties.

The memory of 1926 became seared into the culture and folklore of mining communities as epitomised in Idris Davies’ poem, Do you remember 1926? Certainly, it marked a fracture line in Labour history, as following the lock-out, many miners abandoned the industry and looked for work in the newer industries in the Midlands and South East of England. Hundreds of thousands joined the migrant stream out of the working-class communities of Wales, the North of England and central Scotland, often taking with them their cultural traditions and institutions (see the photo montage below).

But whether they went into ‘exile’ or stayed at ‘home’, the miners were determined to use the memory of their defeat to fight back. W. P. Richardson of the Durham miners expressed their feelings:

The miners are on the bottom and have been compelled to accept dictated and unjust terms. The miners will rise again and will remember because they cannot forget. The victors of today will live to regret their unjust treatment of the miners.

Nevertheless, following its defeat at the hands of the people of Poplar, and in the spirit of class conciliation which followed the General Strike of 1926, both Conservative and Labour governments were naturally cautious in their interventions in the administration of unemployment benefit and poor relief. Although such interventions were subtle, and at times even reluctant, following on from the miners’ dispute, an alliance of the Baldwin Government, leading Civil Servants, together with advocates and adherents of the Social Service movement, had set into motion a cultural counter-revolution which was designed to re-establish their hegemony over industrial areas with large working-class populations. The wartime experience of directing labour resources, and production had given the Coalition ministers a sense of responsibility towards ex-servicemen and it had established several training centres for disabled veterans. The national Government also exercised a limited responsibility, through the Unemployment Grants Committee, together with local authorities, for public works through which the unemployed could be temporarily absorbed. Also, the wartime creation of the Ministry of Labour and a network of employment exchanges provided the means whereby a more adventurous policy could be pursued.

By the end of 1926, the training centres were turning their attention to the wider problem of unemployment, enabling the victims of industrial depression to acquire skills that would facilitate their re-entry into the labour market. Though this often meant resettlement in another area that was not the foremost purpose of the programme. In any case, the regional pattern of unemployment was only just beginning to emerge by the mid-twenties. The Director of the Birmingham Training Centre who went to Wales in 1926 to recruit members for his course was able to offer his audience very little, except lodgings at 18s a week and one free meal a day. The weekly allowance of a trainee was just 23s, and training lasted six months. The real shift in Government policy came in 1927, with Neville Chamberlain invoking his powers as Minister for Health and Local Government to curb Poplarism, under the Bill he had introduced following the General Strike. Commissioners appointed by the Government replaced those local Boards of Guardians that were considered profligate in the administration of the Poor Law.

The Lord Mayor’s fund for distressed miners report, published in ‘The Sphere’, 1929.

The Baldwin government’s second interventionist act was effected through the setting up of the Mansion House Fund in 1928, stemming from the joint appeal of the Lord Mayors of London, Newcastle and Cardiff for help in the relief of the distressed areas. This voluntary approach had, in fact, been initiated by Neville Chamberlain himself, who had written to the Lord Mayor of London in very direct terms:

Surely we cannot be satisfied to leave these unhappy people to go through the winter with only the barest necessities of life.

However, the Government itself acted in support of the voluntary effort rather than taking direct responsibility for it, and it is clear that the main objective of the action was to encourage transference away from the older industrial areas, especially through the provision of boots, clothing and train fare expenses. It was against this background that the Government then established the Industrial Transference Board the following January under the wing of the Ministry of Labour. Much of the initial funding for its work came from the Mansion House Fund. The operation of the Unemployment Grants Committee was carefully directed to conform to this strategy, under advice from the Industrial Transference Board:

As an essential condition for the growth of the will to move, nothing should be done which might tend to anchor men to their home district by holding out an illusory prospect of employment. We therefore reject as unsound policy, relief works in the depressed areas. Such schemes are temporary; at the end the situation is much as before, and the financial resources either at the Exchequer or of the Local Authorities have been drained to no permanent purpose. Grants of assistance such as those made by the Unemployment Grants Committee, which help to finance works carried out by the Local Authority in depressed areas, for the temporary employment of men in those areas, are a negation of the policy which ought in our opinion to be pursued.

As a result, the Government deliberately cut its grants for public works to the depressed areas and instead offered funds at a low rate of interest to prosperous areas on the condition that at least half the men employed on work projects would be drawn from the depressed areas. In August 1928, Baldwin himself made an appeal in the form of a circular, which was distributed throughout the prosperous areas. Every employer who could find work for DA men was asked to contact the nearest Labour Exchange, which would then send a representative to discuss the matter. However, Chamberlain expressed his disappointment over the results of this appeal later that year, and his officials became concerned that the cut-backs made in grants to local authorities for relief work in the depressed areas might lead to a serious level of disorder which would prove minatory to recent poor law policy. The following year, Winston Churchill took responsibility for drafting major sections of the Local Government Act, which reformed the Poor Law and brought about de-rating and a system of block grants. In a speech on the Bill in the Commons, he argued that it was…

… much better to bring industry back to the necessitous areas than to disperse their population, at enormous expense and waste, as if you were removing people from a plague-stricken or malarious region.

However, not for the last time, Churchill’s rhetorical turn of phrase was not appreciated by Chamberlain, who clearly saw in the Bill the means for the more careful management of local authorities, rather than as a means of equalising the effects of the low rateable values of these areas. Of course, Churchill was soon out of office, having held it for four years as Chancellor of the Exchequer, during which time he lowered pensionable age to sixty-five, introduced pensions for widows, and decreased the income-tax rate by ten per cent for the lowest earners among tax-payers.

The Prince of Wales became the Patron of the National Council of Social Services in 1928, a body established to co-ordinate the charitable work of the various charitable organisations which had grown up throughout the decade to ‘dabble’ with the problems of unemployment. That year he made an extensive tour of the depressed areas in South Wales, Tyneside, Scotland and Lancashire, where (above) he is pictured shaking hands with a worker in Middleton. He met men who had already been unemployed for years and, visibly and sincerely shaken, is reported to have said:

Some of the things I see in these gloomy, poverty stricken areas made me almost ashamed to be an Englishman. … isn’t it awful that I can do nothing for them but make them smile.

As the parliamentary year ended, the Labour Party, and in particular its women MPs, could be forgiven for believing that they had much to look forward in the final year of the Twenties. Perhaps one of the changes the ‘flappers’ might have wished to see was a less patronising attitude from the press and their male colleagues than is displayed in the following report…

(to be continued…)

Keir Hardie – The Harbinger of the Independent Labour Party, 1887-88:

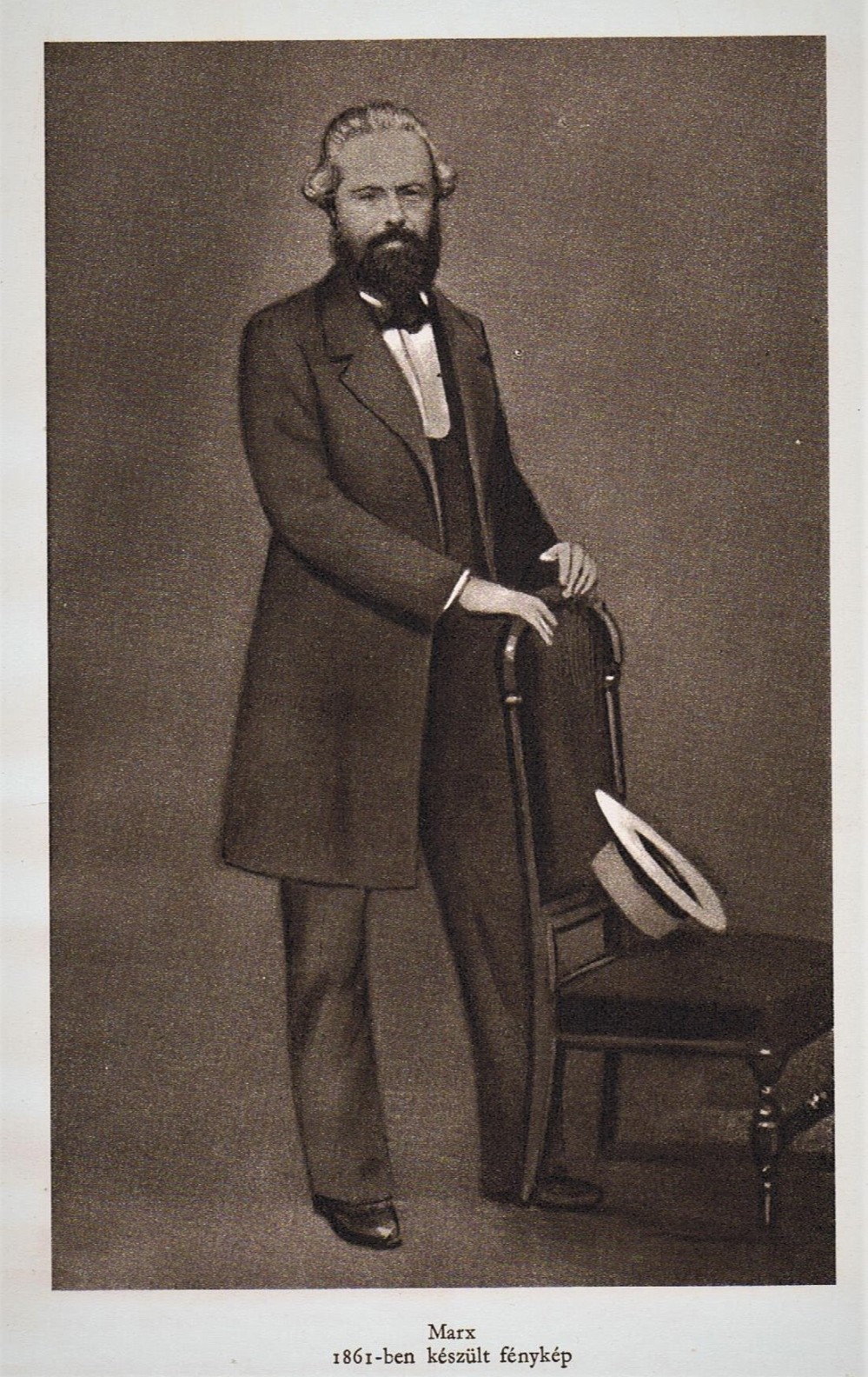

Keir Hardie, who was to play a major role in the political developments of the next three decades, was born into grinding poverty in 1856 in Lanarkshire, the illegitimate son of Mary Kerr, a farm servant who later married a ship’s carpenter named David Hardie. The first years of his life and his early career among the Ayrshire miners are the stuff of legend, but here we are concerned with how he became a Socialist and his contacts with Marxists in London. He had visited the capital with a miners’ delegation in 1887 and attended several meetings of the SDF, where he was introduced to Eleanor Marx, who in turn introduced him to Engels, who was, by then, critical of both the SDF and the Socialist League in Hardie’s hearing. In the end, he did not join the SDF as he had planned to do before arriving in London, and his reasons for his change of mind are instructive about the state of the Socialist movement in Britain at this time:

Born and reared as I had been in the country, the whole environment of the clubs, in which beer seemed to be the most dominant influence, and the tone of the speeches, which were full of denunciation of everything, including trade unionism, and containing little constructive thought, repelled me.

Hardie’s character and politics were not above and beyond the comprehension of the people from whom he had sprung. On the contrary, he was made of the same stuff as they were, with the same instincts, attitudes, the same religious turns of mind and phrase, the same inability to draw a line between politics and morality, or between logic and emotion. His views had already begun developing under the influence of Henry George, from Liberalism to Socialism; but these views were assimilated into his own life and experience, which was something the London Socialists could not share. As the leader and organiser of a trade union and a federation of unions, weak though these organisations were, Hardie was a valuable recruit to the Socialist cause, and his adhesion brought a less academic and more homely voice to the advocacy of independent labour policy. At the beginning of 1887, he had started a monthly magazine, the Miner, in which he addressed the men in his own blunt style, which contained all the aggressive spirit of economic discontent without any of the catchwords of Marxism:

Party be hanged! We are miners first and partisans next, at least if we follow the example of our “superiors” the landlords and their allies, we ought to be. …

He was the harbinger of the New Unionists; and it was fitting that, although his career was to be primarily a political one, he should make his entry into national prominence as a trade union delegate. Already he had taken part in political work, as a Liberal; but now, in the autumn of 1887, he was adopted miners’ Parliamentary candidate for North Ayrshire, and in March 1888, when a vacancy occurred at Mid-Lanark, he was selected as miners’ candidate there, but the Liberal Party chose differently. His supporters encouraged him to stand as an independent and he accepted their nomination. The main principle that Hardie stood for, as an independent labour candidate, was the universal one that the working class must build up its own political strength, stand on its own feet and fight its own battles. This note of sturdy independence, which he struck repeatedly in the course of the by-election campaign, had not often been heard in the course of the preceding decade. He was supported by Champion from the SDF office in London, Tom Mann, Mahon, Donald and a host of other Socialists and Radicals who arrived in the constituency of their own accord. But though the canvassing and rallies were vigorous, there was little doubt about what the outcome would be. Hardie was at the bottom of the poll with 617 votes out of the total of seven thousand votes cast. The Liberal candidate was elected, leading the Conservative by nine hundred votes.

It was a disappointing result at the time, but in retrospect, it is seen as an important political turning-point. There and then, there was no reason to suppose that one or other party, Liberal or Conservative, would not allow itself to become the vehicle for labour representation by a gradual process. But the caucus system which operated within the Liberal Party meant that its choice of candidate was firmly in the control of its middle-class members. The failure of the working-class to break through this stranglehold had the concomitant effect that the Liberal Party’s grip on the working-class vote was clearly weakening in the mid-eighties. Yet its leaders still maintained that they served the interests of working people. Champion, for his part, claimed still more strongly his ambitious claim to be the organiser of the ‘National Labour Party’ and Hardie began the task of forming a Scottish Labour Party.

The Fabian Society & The Socialist Revival of 1889:

The Fabians were also concerned in the task of formulating long-term Socialist policy for the country as a whole. In the autumn of 1888, they organised a series of lectures on The Basis and Prospects of Socialism which were edited by Bernard Shaw and published at the end of 1889, becoming the famous Fabian Essays in Socialism. They provided a distinctive sketch of the political programme of evolutionary Socialism, attracting immediate attention. The first edition at six shillings sold out rapidly and by early 1891, a total of 27,000 copies had been purchased. The seven Fabian essayists, all members of the Society’s Executive, offered a reasoned alternative to the revolutionary Socialist programme. In the first essay, Shaw rejected Marxian analysis of value in favour of a theory of Marginal Utility, asserting the social origin of wealth and reversing the conclusions of laissez-faire political economy from its own premises. In a second essay on the transition to Socialism, Shaw emphasised the importance of the advances towards democracy accomplished by such measures as the County Council Act of 1888. The extinction of private property could, he thought, be gradual, and each act of expropriation should be accompanied by compensation of the individual property-owner at the expense of all.

Nearly all the Fabian essayists postulated a gradual, comparatively even and peaceful evolution of Socialism, which they regarded as already taking place by the extension of political democracy, national and local, and by the progress of ‘gas and water’ Socialism. They regarded the existing political parties, and especially the Liberal-Radicals, as open to permeation by Socialist ideas. Judged by the circumstances of their time, the most striking omission from their whole general thesis was their failure to recognise the significance of the trade unions and co-operative societies. As Sidney Webb (pictured above) was later to discover, conclusions could be drawn from the working of these institutions which would dovetail with his general theory of the inevitability of gradualness. Arguing on historical grounds, Webb suggested that Socialism was already slowly winning the day: by Socialism, he meant the extension of public control, either by the State or the municipality.

Annie Besant looked forward to a decentralised society attaching special importance to municipal Socialism. One of the other essayists, Hubert Bland, however, was hostile on the one hand towards Liberal-Radicalism and on the other towards the ‘catastrophic’ Socialism of the SDF and the Socialist League, but this did not lead him to accept Webb’s view that the extension of State control was necessarily an indication of advance towards Socialism. He could not agree that it was possible to effectively permeate the Radical Left: on the contrary, he predicted, Socialists could expect nothing but opposition from both main parties. His conclusion from this more thoroughly Marxian analysis was that there was a true cleavage being slowly driven through the body politic and that there was, therefore, a need for the formation of a definitively Socialist Party.

Bland’s view was important and, in some ways, future developments confirmed his ideas rather than those of the other essayists. He was certainly more in line with the Championite group, some of whose members were to play a leading role in the foundation of the Labour Party. Among his contemporary Fabian leaders, however, Bland was in a minority of one. The majority, judging national politics from a metropolitan perspective and assuming that the character of Liberalism was the same throughout the country, thought that their policy of permeation was the answer not only for the problems of London County Council but also for the broader sphere of Westminster politics. In the following decades, their association with the metropolitan Liberals was to be the source of great mistrust to the leaders of the growing independent labour movement outside the capital. Consequently, it was not for the immediate political tactics, but for their success in formulating a long-term evolutionary programme, that the Fabians were to be of importance in the eventual foundation of the Labour Party.

Labour Aristocrats, New Unionists & Socialist Internationals, 1889-1894:

In 1874, the trade union membership recorded and represented at the Trades Union Congress had risen to 594,000; but by the end of that decade it had fallen to 381,000, and it was not until 1889 that the 1874 figure was exceeded. Union membership was almost entirely concentrated among more highly-skilled workers, for the first attempts to organise unskilled industrial workers had been killed off by the depression. The term ‘labour aristocracy’, which was used at the time by Marxists to describe the organised workers, is not inappropriate to point out the contrast between the privileges of their position and the weakness of the great mass of the less-skilled workers below them. Bowler-hatted craft unionists like those seen with their giant painted banner at the opening of the Woolwich Free Ferry in March 1889, shown in the photograph below, enjoyed a measure of respectability and a regular wage, the so-called unskilled lived a precarious existence. Balanced between poverty and absolute destitution, they were feared by the middle classes and despised by skilled and organised trade unionists. The Amalgamated Society of Engineers was the third-largest union in Britain by 1890. In 1897-98 it fought long, hard and unsuccessfully for an eight-hour day.

In London alone, there were four thousand casual workers in the 1890s, and thousands were unemployed, homeless and destitute, a submerged population of outcasts who not only filled the workhouses and doss houses but slept in great numbers in the streets. Two of the SDF lantern slides (below) show differing aspects of homelessness, a picture of women spending the night on an embankment seat, taken at four in the morning, and a scene of men washing in a night shelter. The scene of women sleeping on the Embankment was would have been a common sight at the time. R. D. Blumenfeld, an American-born journalist who came to Britain in the 1880s, recorded, in his diary, his experience of a night on the Embankment on 24 December 1901:

I walked along the Embankment this morning at two o’ clock … Every bench from Blackfriars to Westminster Bridge was filled with shivering people, all huddled up – men, women and children. The Salvation Army people were out giving away hot broth, but even this was merely a temporary palliative against the bitter night. At Charing Cross we encountered a man with his wife and two tiny children. They had come to town from Reading to look for work. The man had lost his few shillings and they were stranded …

Charitable institutions were unable to cope with the vast numbers that sought nightly access to their refuges and many of the outcast lacked even the few coppers required for common lodging houses and ‘dossers’. Others preferred the open streets to the casual ward where they ran the risk of being detained for three days against their will and there were hundreds who would chance exposure to the elements rather than submit to the workhouse. After Trafalgar Square was cleared on Bloody Sunday in 1887, the authorities finally banned the Square to the homeless. But the embankment, with its benches and bridges, continued to be used by mothers with babies in arms, children and old people, all spending the night insulated against the cold by old newspapers and sacks. The thousands who slept out were not for the most part alcoholics but honest, poor, unskilled and casual workers, subject to seasonal and trade fluctuations in employment. Salvation Army General Booth in Darkest London quotes a typical case of a Bethnal Green bootmaker, in hospital for three months. His wife also became ill and after three weeks their furniture was seized for rent due to the landlord. Subsequently, they were evicted. Too ill to work, everything pawned, including the tools of his trade, they became dispossessed outcasts. Not all the ‘dossers’ were out of work; many were simply homeless and earned such poor wages that renting rooms was beyond their means. Records from the Medland Hall refuge showed sailors, firemen, painters, bricklayers and shoemakers among those who sought shelter from the streets of the richest city in the world.

Elsewhere in the country, there were some anomalies in the divisions of workers into ‘skilled’ and ‘unskilled’: the Lancashire cotton workers, for example, even though comparatively unskilled, ranked with the ‘aristocracy’, while the Yorkshire woollen workers, probably owing to the greater diversity of their occupations, were almost devoid of organisation. Among the miners, too, the degree of trade unionism varied widely among men of comparable skill in different coalfields. The general labourers and workers in the sweated trades, many of them women, had no unions, and their miserable conditions were at once a cause and a result of their inability to defend themselves. At the bottom of the social heap were the casual labourers, thousands of whom fought daily for work at the gates of London’s docks. The following description of dockers waiting for ‘call on’ was written by Ben Tillett in a little pamphlet entitled A Dock Labourer’s Bitter Cry in July 1887:

There can be nothing ennobling in an atmosphere where we are huddled and herded together like cattle. There is nothing refining in the thought that to obtain employment we were driven into a shed, iron barred from end to end, outside of which a contractor or a foreman walks up and down with the air of a dealer in cattle market, picking and choosing from a crowd of men who in their eagerness to obtain employment, trample each other underfoot, and where they fight like beasts for the chance of a day’s work.