Archive for the ‘homosexuality’ Category

Hungary at the beginning of its Second Millennium:

The Republican George W Bush became US President in January 2001, replacing Bill Clinton, the Democrat and ‘liberal’, whose eight years in the White House had come to an end during the first Orbán government, which lost the general election of 2002. Its Socialist successor was led first by Péter Medgyessy and then, from 2004-09, by Ferenc Gyurcsány (pictured below, on the left).

In this first decade of the new millennium, relations between the ‘West’ and Hungary continued to progress as the latter moved ahead with its national commitment to democracy, the rule of law and a market economy under both centre-right and centre-left governments. They also worked in NATO (from 1999) and the EU (from 2004) to combat terrorism, international crime and health threats. In January 2003, Hungary was one of the eight central and eastern European countries whose leaders signed a letter endorsing US policy during the Iraq Crisis. Besides inviting the US Army to train Free Iraqi Forces as guides, translators and security personnel at the Taszár air base, Hungary also contributed a transportation company of three hundred soldiers to a multinational division stationed in central Iraq. Following Hurricane Katrina, which devastated the Gulf Coast of the United States in the fall of 2005, members of a team of volunteer rescue professionals from Hungarian Baptist Aid were among the first international volunteers to travel to the region, arriving in Mississippi on 3 September. The following April, in response to the severe floods throughout much of Hungary, US-AID provided $50,000 in emergency relief funds to assist affected communities.

During his visit to Budapest in June 2006, in anticipation the fiftieth anniversary of the 1956 Uprising, President George W Bush gave a speech on Gellért Hill in the capital in which he remarked:

“The desire for liberty is universal because it is written into the hearts of every man, woman and child on this Earth. And as people across the world step forward to claim their own freedom, they will take inspiration from Hungary’s example, and draw hope from your success. … Hungary represents the triumph of liberty over tyranny, and America is proud to call Hungary a friend.”

The Origins and Growth of Populism in Europe:

Not without ambivalence, by the end of the first decade of the new millennium, Hungary had stepped out on the Occidental route it had anticipated for more than a century. This is why, from 1998 onwards, Hungarian political developments in general and the rise of FIDESZ-MPP as a formidable populist political force need to be viewed in the context of broader developments within the integrated European liberal democratic system shared by the member states of the European Union. Back in 1998, only two small European countries – Switzerland and Slovakia – had populists in government. Postwar populists found an early toehold in Europe in Alpine countries with long histories of nationalist and/or far-right tendencies. The exclusionist, small-government Swiss People’s Party (SVP) was rooted in ‘authentic’ rural resistance to urban and foreign influence, leading a successful referendum campaign to keep Switzerland out of the European Economic Area (EEA) in 1992, and it has swayed national policy ever since. The Swiss party practically invented right-wing populism’s ‘winning formula’; nationalist demands on immigration, hostility towards ‘neo-liberalism’ and a fierce focus on preserving national traditions and sovereignty. In Austria, neighbour to both Switzerland and Hungary, the Freedom Party, a more straightforward right-wing party founded by a former Nazi in 1956, won more than twenty per cent of the vote in 1994 and is now in government, albeit as a junior partner, for the fourth time.

The immediate effect of the neo-liberal shock in countries like Hungary, Slovakia and Poland was a return to power of the very people who the imposition of a free market was designed to protect their people against, namely the old Communist ‘apparatchiks’, now redefining themselves as “Socialist” parties. They were able to scoop up many of the ‘losers’ under the new system, the majority of voters, the not inconsiderable number who reckoned, probably rightly, that they had been better off under the socialist system, together with the ‘surfers’ who were still in their former jobs, though now professing a different ideology, at least on the surface. In administration and business, the latter were well-placed to exploit a somewhat undiscriminating capitalist capitalism and the potential for corruption in what was euphemistically called “spontaneous” privatisation. Overall, for many people in these transition-challenged countries, the famously witty quip of the ‘losers’ in post-Risorgimento liberal Italy seemed to apply: “we were better off when we were worse off”. The realisation of what was happening nevertheless took some time to seep through into the consciousness of voters. The role of the press and media was crucial in this, despite the claim of Philipp Ther (2014) claim that many…

… journalists, newspapers and radio broadcasters remained loyal to their régimes for many years, but swiftly changed sides in 1989. More than by sheer opportunism, they were motivated by a sense of professional ethics, which they retained despite all Communist governments’ demand, since Lenin’s time, for ‘partynost’ (partisanship).

In reality, journalists were relatively privileged under the old régime, provided they toed the party line, and were determined to be equally so in the new dispensation. Some may have become independent-minded and analytical, but very many more exhibited an event greater partisanship after what the writer Péter Eszterházy called rush hour on the road to Damascus. The initial behaviour of the press after 1989 was a key factor in supporting the claim of the Right, both in Poland and Hungary, that the revolution was only ‘half-completed’. ‘Liberal’ analysis does not accept this and is keen to stress only the manipulation of the media by today’s right-wing governments. But even Paul Lendvai has admitted that, in Hungary, in the first years after the change, the media was mostly sympathetic to the Liberals and former Communists.

On the other hand, he has also noted that both the Antall and the first Orbán government (1998-2002) introduced strong measures to remedy this state of affairs. Apparently, when Orbán complained to a Socialist politician of press bias, the latter suggested that he should “buy a newspaper”, advice which he subsequently followed, helping to fuel ongoing ‘liberal’ complaints about the origins of the one-sided nature of today’s media in Hungary. Either way, Damascene conversions among journalists could be detected under both socialist and conservative nationalist governments.

The Great Financial Meltdown of 2007-2009 & All That!:

The financial meltdown that originated in the US economy in 2007-08 had one common factor on both sides of the Atlantic, namely the excess of recklessly issued credit resulting in massive default, chiefly in the property sector. EU countries from Ireland to Spain to Greece were in virtual meltdown as a result. Former Communist countries adopted various remedies, some taking the same IMF-prescribed medicine as Ireland. It was in 2008, as the financial crisis and recession caused living standards across Europe to shrink, that the established ruling centrist parties began to lose control over their volatile electorates. The Eurocrats in Brussels also became obvious targets, with their ‘clipboard austerity’, especially in their dealings with the Mediterranean countries and with Greece in particular. The Visegrád Four Countries had more foreign direct investment into industrial enterprises than in many other members of the EU, where the money went into ‘financials’ and real estate, making them extremely vulnerable when the crisis hit. Philipp Ther, the German historian of Europe Since 1989, has argued that significant actors, including Václav Klaus in the Czech Republic, preached the ‘gospel of neo-liberalism’ but were pragmatic in its application.

The Man the ‘Populists’ love to hate: Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission since November 2014, when he succeeded Jóse Manuel Barroso. Although seen by many as the archetypal ‘Eurocrat’, by the time he left office as the Prime Minister of Luxembourg, Juncker was the longest-serving head of any national government in the EU, and one of the longest-serving democratically elected leaders in the world, his tenure encompassing the height of the European financial and sovereign debt crisis. From 2005 to 2013, Juncker served as the first permanent President of the Eurogroup.

Dealing with the case of Hungary, László Csaba has expressed his Thoughts on Péter Ákos Bod’s Book, published recently, in the current issue of Hungarian Review (November 2018). In the sixth chapter of his book, Bod admits that the great financial meltdown of 2007-09 did not come out of the blue, and could have been prepared for more effectively in Hungary. Csaba finds this approach interesting, considering that the recurrent motif in the international literature of the crisis has tended to stress the general conviction among ‘experts’ that nothing like what happened in these years could ever happen again. Bod points out that Hungary had begun to lag behind years before the onslaught of the crisis, earlier than any of its neighbours and the core members of the EU. The application of solutions apparently progressive by international standards often proved to be superficial in their effects, however. In reality, the efficiency of governance deteriorated faster than could have been gleaned from macroeconomic factors. This resulted in excessive national debt and the IMF had to be called in by the Socialist-Liberal coalition. The country’s peripheral position and marked exposure were a given factor in this, but the ill-advised decisions in economic policy certainly added to its vulnerability. Bod emphasises that the stop-and-go politics of 2002-2010 were heterodox: no policy advisor or economic textbook ever recommended a way forward, and the detrimental consequences were accumulating fast.

As a further consequence of the impact of the ongoing recession on the ‘Visegrád’ economies, recent statistical analyses by Thomas Piketty have shown that between 2010 and 2016 the annual net outflow of profits and incomes from property represented on average 4.7 per cent of GDP in Poland, 7.2 per cent in Hungary, 7.6 per cent in the Czech Republic and 4.2 per cent in Slovakia, reducing commensurately the national income of these countries. By comparison, over the same period, the annual net transfers from the EU, i.e. the difference between the totality of expenditure received and the contributions paid to the EU budget were appreciably lower: 2.7 per cent of GDP in Poland, 4.0 per cent in Hungary, 1.9 per cent in the Czech Republic and 2.2 per cent in Slovakia. Piketty added that:

East European leaders never miss an opportunity to recall that investors take advantage of their position of strength to keep wages low and maintain excessive margins.

He cites a recent interview with the Czech PM in support of this assertion. The recent trend of the ‘Visegrád countries’ to more nationalist and ‘populist’ governments suggests a good deal of disillusionment with global capitalism. At the very least, the theory of “trickle down” economics, whereby wealth created by entrepreneurs in the free market, assisted by indulgent attitudes to business on the part of the government, will assuredly filter down to the lowest levels of society, does not strike the man on the Budapest tram as particularly plausible. Gross corruption in the privatisation process, Freunderlwirtschaft, abuse of their privileged positions by foreign investors, extraction of profits abroad and the volatility of “hot money” are some of the factors that have contributed to the disillusionment among ‘ordinary’ voters. Matters would have been far worse were it not for a great deal of infrastructural investment through EU funding. Although Poland has been arguably the most “successful” of the Visegrád countries in economic terms, greatly assisted by its writing off of most of its Communist-era debts, which did not occur in Hungary, it has also moved furthest to the right, and is facing the prospect of sanctions from the EU (withdrawal of voting rights) which are also, now, threatened in Hungary’s case.

Bod’s then moves on to discuss the economic ‘recovery’ from 2010 to 2015. The former attitude of seeking compromise was replaced by sovereignty-based politics, coupled with increasingly radical government decisions. What gradually emerged was an ‘unorthodox’ trend in economic management measures, marking a break with the practices of the previous decade and a half, stemming from a case-by-case deliberation of government and specific single decisions made at the top of government. As such, they could hardly be seen as revolutionary, given Hungary’s historical antecedents, but represented a return to a more authoritarian form of central government. The direct peril of insolvency had passed by the middle of 2012, employment had reached a historic high and the country’s external accounts began to show a reliable surplus.

Elsewhere in Europe, in 2015, Greece elected the radical left-wing populists of Syriza, originally founded in 2004 as a coalition of left-wing and radical left parties, into power. Party chairman Alexis Tsipras served as Prime Minister of Greece from January 2015 to August 2015 and, following subsequent elections, from September 2015 to the present. In Spain, meanwhile, the anti-austerity Podemos took twenty-one per cent of the vote in 2015 just a year after the party was founded. Even in famously liberal Scandinavia, nation-first, anti-immigration populists have found their voice over the last decade. By 2018, eleven countries have populists in power and the number of Europeans ruled by them has increased from fourteen million to 170 million. This has been accounted for by everything from the international economic recession to inter-regional migration, the rise of social media and the spread of globalisation. Recently, western Europe’s ‘solid inner circle’ has started to succumb. Across Europe as a whole, right-wing populist parties, like Geert Wilder’s (pictured above) anti-Islam Freedom Party (PVV) in the Netherlands, have also succeeded in influencing policy even when not in government, dragging the discourse of their countries’ dominant centre-right parties further to the Right, especially on the issues of immigration and migration.

The Migration Factor & the Crisis of 2015:

Just four momentous years ago, in her New Year message on 31 December 2014, Chancellor Merkel (pictured right) singled out these movements and parties for criticism, including Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), founded in direct response to her assertion at the height of the financial crisis that there was “no alternative” to the EU bailing out Greece. The German people, she insisted, must not have “prejudice, coldness or hatred” in their hearts, as these groups did. Instead, she urged the German people to a new surge of openness to refugees.

Apart from the humanitarian imperative, she argued, Germany’s ‘ageing population’ meant that immigration would prove to be a benefit for all of us. The following May, the Federal Interior Minister announced in Berlin that the German government was expecting 450,000 refugees to arrive in the country that coming year. Then in July 1915, the human tragedy of the migration story burst into the global news networks. In August, the German Interior Ministry had already revised the country’s expected arrivals for 2015 up to 800,000, more than four times the number of arrivals in 2014. The Federal Office for Migration and Refugees pondered the question of what they would do with the people coming up through Greece via ‘the Balkan route’ to Hungary and on to Germany. Would they be sent back to Hungary as they ought to have been under international protocols? An agreement was reached that this would not happen, and this was announced on Twitter on 25 August which said that we are no longer enforcing the Dublin procedures for Syrian citizens. Then, on 31 August, Angela Merkel told an audience of foreign journalists in Berlin that German flexibility was what was needed. She then went on to argue that Europe as a whole…

“… must move and states must share the responsibility for refugees seeking asylum. Universal civil rights were so far tied together with Europe and its history. If Europe fails on the question of refugees, its close connection with universal civil rights will be destroyed. It won’t be the Europe we imagine. … ‘Wir schaffen das’ (‘We can do this’).“

Much of the international media backed her stance, The Economist claiming that Merkel the bold … is brave, decisive and right. But across the continent ‘as a whole’ Merkel’s unilateral decision was to create huge problems in the coming months. In a Europe whose borders had come down and in which free movement had become a core principle of the EU, the mass movement through Europe of people from outside those borders had not been anticipated. Suddenly, hundreds of thousands were walking through central Europe on their way north and west to Germany, Denmark and Sweden. During 2015 around 400,000 migrants moved through Hungary’s territory alone. Fewer than twenty of them stopped to claim asylum within Hungary, but their passage through the country to the railway stations in Budapest had a huge impact on its infrastructure and national psychology.

By early September the Hungarian authorities announced that they were overwhelmed by the numbers coming through the country and declared the situation to be out of control. The government tried to stop the influx by stopping trains from leaving the country for Austria and Germany. Around fourteen thousand people were arriving in Munich each day. Over the course of a single weekend, forty thousand new arrivals were expected. Merkel had her spokesman announce that Germany would not turn refugees away in order to help clear the bottleneck in Budapest, where thousands were sleeping at the Eastern Station, waiting for trains. Some were tricked into boarding a train supposedly bound for Austria which was then held near a detention camp just outside Budapest. Many of the ‘migrants’ refused to leave the train and eventually decided to follow the tracks on foot back to the motorway and on to the border in huge columns comprising mainly single men, but also many families with children.

These actions led to severe criticism of Hungary in the international media and from the heads of other EU member states, both on humanitarian grounds but also because Hungary appeared to be reverting to national boundaries. But the country had been under a huge strain not of its own making. In 2013 it had registered around twenty thousand asylum seekers. That number had doubled in 2014, but during the first three winter months of 2015, it had more people arriving on its southern borders than in the whole of the previous year. By the end of the year, the police had registered around 400,000 people, entering the country at the rate of ten thousand a day. Most of them had come through Greece and should, therefore, have been registered there, but only about one in ten of them had been. As the Hungarians saw it, the Greeks had simply failed to comply with their obligations under the Schengen Agreement and EU law. To be fair to them, however, the migrants had crossed the Aegean sea by thousands of small boats, making use of hundreds of small, poorly policed islands. This meant that the Hungarian border was the first EU land border they encountered on the mainland.

Above: Refugees are helped by volunteers as they arrive on the Greek island of Lesbos.

In July the Hungarian government began constructing a new, taller fence along the border with Serbia. This increased the flow into Croatia, which was not a member of the EU at that time, so the fence was then extended along the border between Croatia and Hungary. The Hungarian government claimed that these fences were the only way they could control the numbers who needed to be registered before transit, but they were roundly condemned by the Slovenians and Austrians, who now also had to deal with huge numbers on arriving on foot. But soon both Austria and Slovenia were erecting their own fences, though the Austrians claimed that their fence was ‘a door with sides’ to control the flow rather than to stop it altogether. The western European governments, together with the EU institutions’ leaders tried to persuade central-European countries to sign up to a quota system for relocating the refugees across the continent, Viktor Orbán led a ‘revolt’ against this among the ‘Visegrád’ countries.

Douglas Murray has recently written in his best-selling book (pictured right, 2017/18) that the Hungarian government were also reflecting the will of their people in that a solid two-thirds of Hungarians polled during this period felt that their government was doing the right thing in refusing to agree to the quota number. In reality, there were two polls held in the autumn of 2015 and the spring of 2016, both of which had returns of less than a third, of whom two-thirds did indeed agree to a loaded question, written by the government, asking if they wanted to “say ‘No’ to Brussels”. In any case, both polls were ‘consultations’ rather than mandatory referenda, and on both occasions, all the opposition parties called for a boycott. Retrospectively, Parliament agreed to pass the second result into law, changing the threshold to two-thirds of the returns and making it mandatory.

Murray has also claimed that the financier George Soros, spent considerable sums of money during 2015 on pressure groups and institutions making the case for open borders and free movement of migrants into and around Europe. The ideas of Karl Popper, the respected philosopher who wrote The Open Society and its Enemies have been well-known since the 1970s, and George Soros had first opened the legally-registered Open Society office in Budapest in 1987.

Soros certainly helped to found and finance the Central European University as an international institution teaching ‘liberal arts’ some twenty-five years ago, which the Orbán government has recently been trying to close by introducing tighter controls on higher education in general. Yet in 1989 Orbán himself received a scholarship from the Soros Foundation to attend Pembroke College, Oxford but returned after a few months to become a politician and leader of FIDESZ.

However, there is no evidence to support the claim that Soros’ foundation published millions of leaflets encouraging illegal immigration into Hungary, or that the numerous groups he was funding were going out of their way to undermine the Hungarian government or any other of the EU’s nation states.

Soros’ statement to Bloomberg that his foundation was upholding European values that Orbán, through his opposition to refugee quotas was undermining would therefore appear to be, far from evidence a ‘plot’, a fairly accurate reiteration of the position taken by the majority of EU member states as well as the ‘Brussels’ institutions. Soros’ plan, as quoted by Murray himself, treats the protection of refugees as the objective and national borders as the obstacle. Here, the ‘national borders’ of Hungary he is referring to are those with other surrounding EU states, not Hungary’s border with Serbia. So Soros is referring to ‘free movement’ within the EU, not immigration from outside the EU across its external border with Serbia. During the 2015 Crisis, a number of churches and charitable organisations gave humanitarian assistance to the asylum seekers at this border. There is no evidence that any of these groups received external funding, advocated resistance against the European border régime or handed out leaflets in Serbia informing the recipients of how to get into Europe.

Viktor Orbán & The Strange Case of ‘Illiberal Democracy’:

On 15 March 2016, the Prime Minister of Hungary used the ceremonial speech for the National Holiday commemorating the 1848 Revolution to explain his wholly different approach to migration, borders, culture and identity. Viktor Orbán told those assembled by the steps of the National Museum that, in Douglas Murray’s summation, the new enemies of freedom were different from the imperial and Soviet systems of the past, that today they did not get bombarded or imprisoned, but merely threatened and blackmailed. In his own words, the PM set himself up as the Christian champion of Europe:

At last, the peoples of Europe, who have been slumbering in abundance and prosperity, have understood that the principles of life that Europe has been built on are in mortal danger. Europe is the community of Christian, free and independent nations…

Mass migration is a slow stream of water persistently eroding the shores. It is masquerading as a humanitarian cause, but its true nature is the occupation of territory. And what is gaining territory for them is losing territory for us. Flocks of obsessed human rights defenders feel the overwhelming urge to reprimand us and to make allegations against us. Allegedly we are hostile xenophobes, but the truth is that the history of our nation is also one of inclusion, and the history of intertwining of cultures. Those who have sought to come here as new family members, as allies, or as displaced persons fearing for their lives, have been let in to make new homes for themselves.

But those who have come here with the intention of changing our country, shaping our nation in their own image, those who have come with violence and against our will have always been met with resistance.

Yet behind these belligerent words, and in other comments and speeches, Viktor Orbán has made clear that his government is opposed taking in its quota of Syrian refugees on religious and cultural grounds. Robert Fico, the Slovakian leader, made this explicit when he stated just a month before taking over the Presidency of the European Union, that…

… Islam has no place in Slovakia: Migrants change the character of our country. We do not want the character of this country to change.

It is in the context of this tide of unashamed Islamaphobia in central and eastern Europe that right-wing populism’s biggest advances have been made. All four of the Visegrád countries (the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Hungary) are governed by populist parties. None of these countries has had any recent experience of immigration from Muslim populations in Africa or the Indian subcontinent, unlike many of the former imperial powers of western Europe. Having had no mass immigration during the post-war period, they had retained, in the face of Soviet occupation and dominance, a sense of national cohesion and a mono-cultural character which supported their needs as small nations with distinct languages. They also distrusted the West, since they had suffered frequent disappointments in their attempts to assert their independence from Soviet control and had all experienced, within living memory, the tragic dimensions of life that the Western allies had forgotten. So, too, we might add, did the Baltic States, a fact which is sometimes conveniently ignored. The events of 1956, 1968, 1989 and 1991 had revealed how easily their countries could be swept in one direction and then swept back again. At inter-governmental levels, some self-defined ‘Islamic’ countries have not helped the cause of the Syrian Muslim refugees. Iran, which has continued to back the Hezbollah militia in its fighting for Iranian interests in Syria since 2011, has periodically berated European countries for not doing more to aid the refugees. In September 2015, President Rouhani lectured the Hungarian Ambassador to Iran over Hungary’s alleged ‘shortcomings’ in the refugee crisis.

For their part, the central-eastern European states continued in their stand-off with ‘Berlin and Brussels’. The ‘Visegrád’ group of four nations have found some strength in numbers. Since they continued to refuse migrant quotas, in December 2017 the European Commission announced that it was suing Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic at the European Court of Justice over this refusal. Sanctions and heavy fines were threatened down the line, but these countries have continued to hold out against these ‘threats’. But Viktor Orbán’s Hungary has benefited substantially from German investment, particularly in the auto industry. German business enjoys access to cheap, skilled and semi-skilled labour in Hungary, while Hungary benefits from the jobs and the tax revenue flowing from the investment. German business is pragmatic and generally ignores political issues as long as the investment climate is right. However, the German political class, and especially the German media, have been forcibly critical of Viktor Orbán, especially over the refugee and migrant issues. As Jon Henley reports, there are few signs of these issues being resolved:

Philipp Ther’s treatment of Hungary in his History (2016) follows this line of criticism. He describes Orbán as being a ‘bad loser’ in the 2002 election and a ‘bad winner’ in 2010. Certainly, FIDESZ only started showing their true populist colours after their second victory in 2006, determined not to lose power after just another four years. They have now won four elections in succession.

Viktor Orbán speaking during the 2018 Election campaign: “Only Fidesz!”

John Henley, European Affairs Correspondent of The Guardian, identifies the core values of FIDESZ as those of nationalism, cultural conservatism and authoritarianism. For the past decade, he claims, they have been attacking the core institutions of any liberal democracy, including an independent judiciary and a free press/ media. He argues that they have increasingly defined national identity and citizenship in terms of ethnicity and religion, demonising opponents, such as George Soros, in propaganda which is reminiscent of the anti-Semitism of the 1930s. This was particularly the case in the 2018 election campaign, in which ubiquitous posters showed him as the ‘puppet-master’ pulling the strings of the opposition leaders. In the disputed count, the FIDESZ-KDNP (Christian Democrat) Alliance in secured sixty-three per cent of the vote. The OSCE observers commented on the allusions to anti-Semitic tropes in the FIDESZ-KDNP campaign. In addition, since the last election, Jon Henley points out how, as he sees it, FIDESZ’s leaders have ramped up their efforts to turn the country’s courts into extensions of their executive power, public radio and television stations into government propaganda outlets, and universities into transmitters of their own narrowly nationalistic and culturally conservative values. Philipp Ther likewise accuses Orbán’s government of infringing the freedom of the press, and of ‘currying favour’ by pledging to put the international banks in their place (the miss-selling of mortgages in Swiss Francs was egregious in Hungary).

Defenders of Viktor Orbán’s government and its FIDESZ-KDNP supporters will dismiss this characterisation as stereotypical of ‘western liberal’ attacks on Orbán, pointing to the fact that he won forty-nine per cent of the popular vote in the spring elections and a near two-thirds parliamentary majority because the voters thought that overall it had governed the country well and in particular favoured its policy on migration, quotas and relocation. Nicholas T Parsons agrees that Orbán has reacted opportunistically to the unattractive aspects of inward “investment”, but says that it is wishful thinking to interpret his third landslide victory as in April 2018 as purely the result of manipulation of the media or the abuse of power. However, in reacting more positively to Ther’s treatment of economic ‘neo-liberalism’, Parsons mistakenly conflates this with his own attacks on ‘liberals’, ‘the liberal establishment’ and ‘the liberal élite’. He then undermines his own case by hankering after a “Habsburg solution” to the democratic and nationalist crisis in the “eastern EU”. To suggest that a democratic model for the region can be based on the autocratic Austro-Hungarian Empire which finally collapsed in abject failure over a century ago is to stand the history of the region case on its head. However, he makes a valid point in arguing that the “western EU” could do more to recognise the legitimate voice of the ‘Visegrád Group’.

Nevertheless, Parsons overall claim that Orbán successfully articulates what many Hungarians feel is shared by many close observers. He argues that…

… commentary on the rightward turn in Central Europe has concentrated on individual examples of varying degrees of illiberalism, but has been too little concerned with why people are often keen to vote for governments ritualistically denounced by the liberal establishment as ‘nationalist’ and ‘populist’.

Gerald Frost, a staff member of the Danube Institute, recently wrote to The Times that while he did not care for the policies of the Orbán government, Hungary can be forgiven for wishing to preserve its sovereignty. But even his supporters recognise that his ‘innocent’ coining of the term “illiberal democracy” in a speech to young ethnic Hungarians in Transylvania in 2016. John O’Sullivan interpreted this at the time as referring to the way in which under the rules of ‘liberal democracy’, elected bodies have increasingly ceded power to undemocratic institutions like courts and unelected international agencies which have imposed ‘liberal policies’ on sovereign nation states. But the negative connotations of the phrase have tended to obscure the validity of the criticism it contains. Yet the Prime Minister has continued to use it in his discourse, for example in his firm response to the European Parliament’s debate on the Sargentini Report (see the section below):

Illiberal democracy is when someone else other than the liberals have won.

At least this clarifies that he is referring to the noun rather than to the generic adjective, but it gets us no further in the quest for a mutual understanding of ‘European values’. As John O’Sullivan points out, until recently, European politics has been a left-right battle between the socialists and the conservatives which the liberals always won. That is now changing because increasing numbers of voters, often in the majority, disliked, felt disadvantaged by, and eventually opposed policies which were more or less agreed between the major parties. New parties have emerged, often from old ones, but equally often as completely new creations of the alienated groups of citizens. In the case of FIDESZ, new wine was added to the old wine-skin of liberalism, and the bag eventually burst. A new basis for political discourse is gradually being established throughout Europe. The new populist parties which are arising in Europe are expressing resistance to progressive liberal policies. The political centre, or consensus parties, are part of an élite which have greater access to the levers of power and which views “populism” as dangerous to liberal democracy. This prevents the centrist ‘establishment’ from making compromises with parties it defines as extreme. Yet voter discontent stems, in part, from the “mainstream” strategy of keeping certain issues “out of politics” and demonizing those who insist on raising them.

“It’s the Economy, stupid!” – but is it?:

In the broader context of central European electorates, it also needs to be noted that, besides the return of Jaroslaw Kaczynski’s Law and Justice Party in Poland, and the continued dominance of populist-nationalists in Slovakia, nearly a third of Czech voters recently backed the six-year-old Ano party led by a Trump-like businessman and outsider, who claims to be able to get things done in a way that careerist politicians cannot. But, writes Henley, the Czech Republic is still a long way from becoming another Hungary or Poland. Just 2.3% of the country’s workforce is out of a job, the lowest rate anywhere in the EU. Last year its economy grew by 4.3%, well above the average in central-Eastern Europe, and the country was untouched by the 2015 migration crisis. But in the 2017 general election, the populists won just over forty per cent of votes, a tenfold increase since 1998. Martin Mejstrik, from Charles University in Prague, commented to Henley:

“Here, there has been no harsh economic crisis, no big shifts in society. This is one of the most developed and successful post-communist states. There are, literally, almost no migrants. And nonetheless, people are dissatisfied.”

Henley also quotes Jan Kavan, a participant in the Prague Spring of 1968, and one of the leaders of today’s Czech Social Democrats, who like the centre-left across Europe, have suffered most from the populist surge, but who nevertheless remains optimistic:

“It’s true that a measure of populism wins elections, but if these pure populists don’t combine it with something else, something real… Look, it’s simply not enough to offer people a feeling that you are on their side. In the long-term, you know, you have to offer real solutions.”

By contrast with the data on the Czech Republic, Péter Ákos Bod’s book concludes that the data published in 2016-17 failed to corroborate the highly vocal opinions about the exceptional performance of the Hungarian economy. Bod has found that the lack of predictability, substandard government practices, and the string of non-transparent, often downright suspect transactions are hardly conducive to long-term quality investments and an enduring path of growth they enable. He finds that Hungary does not possess the same attributes of a developed state as are evident in the Czech Republic, although the ‘deeper involvement and activism’ on the part of the government than is customary in western Europe ‘is not all that alien’ to Hungary given the broader context of economic history. László Csaba concludes that if Bod is correct in his analysis that the Hungarian economy has been stagnating since 2016, we must regard the Hungarian victory over the recent crisis as a Pyrrhic one. He suggests that the Orbán government cannot afford to hide complacently behind anti-globalisation rhetoric and that, …

… in view of the past quarter-century, we cannot afford to regard democratic, market-oriented developments as being somehow pre-ordained or inevitable.

Above: Recent demonstrations against the Orbán government’s policies in Budapest.

By November 2018, it was clear that Steve Bannon (pictured below with the leader of the far-right group, Brothers of Italy, Giorgi Meloni and the Guardian‘s Paul Lewis in Venice), the ex-Trump adviser’s attempt to foment European populism ahead of the EU parliamentary elections in 2019, was failing to attract support from any of the right-wing parties he was courting outside of Italy. Viktor Orbán has signalled ambivalence about receiving a boost from an American outsider, which would undermine the basis of his campaign against George Soros. The Polish populists also said they would not join his movement, and after meeting Bannon in Prague, the populist president of the Czech Republic, Milos Zeman, remained far from convinced, as he himself reported:

“He asked for an audience, got thirty minutes, and after thirty minutes I told him I absolutely disagree with his views and I ended the audience.”

The ‘Furore’ over the Sargentini Report:

In Hungary, the European Parliament’s overwhelming acceptance of the Sargentini Report has been greeted with ‘outrage’ by many Hungarian commentators and FIDESZ supporters. Judith Sargentini (pictured right) is a Dutch politician and Member of the European Parliament (MEP), a member of the Green Left. Her EP report alleges, like the Guardian article quoted above, that democracy, the rule of law, and fundamental human rights are under systematic threat in Hungary.

The subsequent vote in the European Parliament called for possible sanctions to be put in place, including removal of the country’s voting rights within the EU institutions. FIDESZ supporters argue that the European Parliament has just denounced a government and a set of policies endorsed by the Hungarian electorate in a landslide. The problem with this interpretation is that the policies which were most criticised in the EU Report were not put to the electorate, which was fought by FIDESZ-KDNP on the migration issue to the exclusion of all others, including the government’s performance on the economy. Certainly, the weakness and division among the opposition helped its cause, as voters were not offered a clear, unified, alternative programme.

But does the EU’s criticism of Hungary really fit into this “pattern” as O’Sullivan describes it, or an international left-liberal “plot”? Surely the Sargentini Report is legitimately concerned with the Orbán government’s blurring of the separation of powers within the state, and potential abuses of civil rights and fundamental freedoms, and not with its policies on immigration and asylum. Orbán may indeed be heartily disliked in Brussels and Strasbourg for his ‘Eurosceptic nationalism’, but neither the adjective nor the noun in this collocation is alien to political discourse across Europe; east, west or centre. Neither is the concept of ‘national sovereignty’ peripheral to the EU’s being; on the contrary, many would regard it as a core value, alongside ‘shared sovereignty’.

What appears to be fuelling the conflict between Budapest, Berlin and Brussels is the failure to find common ground on migration and relocation quotas. But in this respect, it seems, there is little point in continually re-running the battle over the 2015 migration crisis. Certainly, O’Sullivan is right to suggest that the European Parliament should refrain from slapping Orbán down to discourage other “populists” from resisting its politics of historical inevitability and ever-closer union. Greater flexibility is required on both sides if Hungary is to remain within the EU, and the action of the EP should not be confused with the Commission’s case in the ECJ, conflated as ‘Brussels’ mania. Hungary will need to accept its responsibilities and commitments as a member state if it wishes to remain as such. One of the salient lessons of the ‘Brexit’ debates and negotiations is that no country, big or small, can expect to keep all the benefits of membership without accepting all its obligations.

In the latest issue of Hungarian Review (November 2018), there are a series of articles which come to the defence of the Orbán government in the wake of the Strasbourg vote in favour of adopting the Sargentini Report and threatening sanctions against Hungary. These articles follow many of the lines taken by O’Sullivan and other contributors to earlier editions but are now so indignant that we might well wonder how their authors can persist in supporting Hungary’s continued membership of an association of ‘liberal democratic’ countries whose values they so obviously despise. They are outraged by the EP resolution’s criticism of what it calls the Hungarian government’s “outdated and conservative moral beliefs” such as conventional marriage and policies to strengthen the traditional family. He is, of course, correct in asserting that these are matters for national parliaments by the founding European treaties and that they are the profound moral beliefs of a majority or large plurality of Europeans.

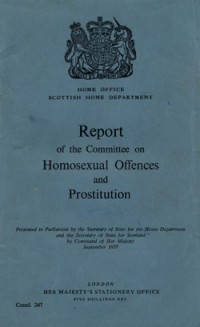

But the fact remains that, while that ‘majority’ or ‘plurality’ may still hold to these biblically based beliefs, many countries have also decided to recognise same-sex marriage as a secular civil right. This has been because, alongside the ‘majoritarian’ principle, they also accept that the role of liberal democracies is to protect and advance the equal rights of minorities, whether defined by language, ethnicity, nationality or sexual preference. In other words, the measure of democratic assets or deficits of any given country is therefore determined by how well the majority respects the right of minorities. In countries where religious organisations are allowed to register marriages, such as the UK, religious institutions are nevertheless either excluded or exempted from solemnising same-sex marriages. In many other countries, including Hungary and France, the legal registration of marriages can only take place in civic offices in any case. Yet, in 2010, the Hungarian government decided to prescribe such rights by including the ‘Christian’ definition of marriage as a major tenet of its new constitution. Those who have observed Hungary both from within and outside questioned at the time what its motivation was for doing this and why it believed that such a step was necessary. There is also the question as to whether Hungary will accept same-sex marriages legally registered in other EU countries on an equal basis for those seeking a settled status within the country.

O’Sullivan, as editor of Hungarian Review, supports Ryszard Legutko’s article on ‘The European Union’s Democratic Deficit’ as being coolly-reasoned. It has to be said that many observers across Europe would indeed agree that the EU has its own ‘democratic deficit’, which they are determined to address. On finer points, while Legutko is right to point out that violence against Jewish persons and property has been occurring across Europe. But it cannot be denied, as he seeks to do, that racist incident happen here in Hungary too. In the last few years, it has been reported in the mainstream media that rabbis have been spat on in the streets and it certainly the case that armed guards have had to be stationed at the main ‘Reformed’ synagogue in Budapest, not simply to guard against ‘Islamic’ terrorism, we are told, but also against attacks from right-wing extremists.

Legutko also labels the Central European University as a ‘foreign’ university, although it has been operating in the capital for more than twenty-five years. It is now, tragically in the view of many Hungarian academics, being forced to leave for no other reason than that it was originally sponsored by George Soros’ Open Society Foundation. The ‘common rules’ which Legutko accepts have been ‘imposed’ on all universities and colleges relate to the curriculum, limiting academic freedom, and bear no relation to the kinds of administrative regulation which apply in other member states, where there is respect for the freedom of the institutions to offer the courses they themselves determine. Legutko’s other arguments, using terms like ‘outrageous’, ‘ideological crusade’, and ‘leftist crusaders’ are neither, in O’Sullivan’s terms, ‘cool’ nor ‘reasoned’.

György Schöpflin’s curiously titled article, What If? is actually a series of rather extreme statements, but there are some valid points for discussion among these. Again, the article is a straightforward attack on “the left” both in Hungary and within the European Parliament. The ‘opposition’ in Hungary is certainly ‘hapless’ and ‘fragmented’, but this does not absolve the Hungarian government from addressing the concerns of the 448 MEPs who voted to adopt the Sargentini report, including many from the European People’s Party to which the FIDESZ-MPP-KDNP alliance still belongs, for the time being at least. Yet Schöpflin simply casts these concerns aside as based on a Manichean view in which the left attributes all virtue to itself and all vice to Fidesz, or to any other political movement that questions the light to the left. Presumably, then, his definition of the ‘left’ includes Conservatives, Centrists and Christian Democrats from across the EU member states, in addition to the Liberal and Social Democratic parties. Apparently, this complete mainstream spectrum has been duped by the Sargentini Report, which he characterises as a dystopic fabrication:

Dystopic because it looked only for the worst (and found it) and fabrication because it ignored all the contrary evidence.

Yet, on the main criticisms of the Report, Schöpflin produces no evidence of his own to refute the ‘allegations’. He simply refers to the findings of the Venice Commission and the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency which have been less critical and more supportive in relation to Hungary’s system of Justice. Fair enough, one might say, but doesn’t this simply give the lie to his view of the EU as a monolithic organisation? Yet his polemic is unrelenting:

The liberal hegemony has increasingly acquired many of the qualities of a secular belief system – unconsciously mimicking Christian antecedents – with a hierarchy of public and private evils. Accusations substitute for evidence, but one can scourge one’s opponents (enemies increasingly) by calling them racist or nativist or xenophobic. … Absolute evil is attributed to the Holocaust, hence Holocaust denial and Holocaust banalisation are treated as irremediably sinful, even criminal in some countries. Clearly, the entire area is so strongly sacralised or tabooised that it is untouchable.

The questions surrounding the events of 1944-45 in Europe are not ‘untouchable’. On the contrary, they are unavoidable, as the well-known picture above continues to show. Here, Schöpflin seems to be supporting the current trend in Hungary for redefining the Holocaust, if not denying it. This is part of a government-sponsored project to absolve the Horthy régime of its responsibility for the deportation of some 440,000 Hungarian Jews in 1944, under the direction of Adolf Eichmann and his henchmen, but at the hands of the Hungarian gendarmerie. Thankfully, Botond Gaál’s article on Colonel Koszorús later in this edition of Hungarian Review provides further evidence of this culpability at the time of the Báky Coup in July 1944.

The questions surrounding the events of 1944-45 in Europe are not ‘untouchable’. On the contrary, they are unavoidable, as the well-known picture above continues to show. Here, Schöpflin seems to be supporting the current trend in Hungary for redefining the Holocaust, if not denying it. This is part of a government-sponsored project to absolve the Horthy régime of its responsibility for the deportation of some 440,000 Hungarian Jews in 1944, under the direction of Adolf Eichmann and his henchmen, but at the hands of the Hungarian gendarmerie. Thankfully, Botond Gaál’s article on Colonel Koszorús later in this edition of Hungarian Review provides further evidence of this culpability at the time of the Báky Coup in July 1944.

But there are ‘official’ historians currently engaged in creating a false narrative that the Holocaust in Hungary should be placed in the context of the later Rákósi terror as something which was directed from outside Hungary by foreign powers, and done to Hungarians, rather than something which Hungarians did to each other and in which Admiral Horthy’s Regency régime was directly complicit. This is part of a deliberate attempt at the rehabilitation and restoration of the reputation of the mainly authoritarian governments of the previous quarter century, a process which is visible in the recent removal and replacement public memorials and monuments.

I have dealt with these issues in preceding articles on this site. Schöpflin then goes on to challenge other ‘taboos’ in ‘the catalogue of evils’ such as colonialism and slavery in order to conclude that:

The pursuit of post-colonial guilt is arguably tied up with the presence of former colonial subjects in the metropole, as an instrument for silencing any voices that might be audacious enough to criticise Third World immigration.

We can only assume here that by using the rather out-dated term ‘Third World’ he is referring to recent inter-regional migration from the Middle East, Africa and the Asian sub-continent. Here, again, is the denial of migration as a fact of life, not something to be criticised, in the way in which much of the propaganda on the subject, especially in Hungary, has tended to demonise migrants and among them, refugees from once prosperous states destroyed by wars sponsored by Europeans and Americans. These issues are not post-colonial, they are post-Cold War, and Hungary played its own (small) part in them, as we have seen. But perhaps what should concern us most here is the rejection, or undermining of universal values and human rights, whether referring to the past or the present. Of course, if Hungary truly wants to continue to head down this path, then it would indeed be logical for it to disassociate itself from all international organisations, including NATO and the UN agencies and organisations. All of these are based on concepts of absolute, regional and global values.

So, what are Schöpflin’s what ifs?? His article refers to two:

-

What if the liberal wave, no more than two-three decades old, has peaked? What if the Third Way of the 1990s is coming to its end and Europe is entering a new era in which left-liberalism will be just one way of doing politics among many?

‘Liberalism’ in its generic sense, defined by Raymond Williams (1983) among others, is not, as this series of articles have attempted to show, a ‘wave’ on the pan-European ‘shoreline’. ‘Liberal Democracy’ has been the dominant political system among the nation-states of Europe for the past century and a half. Hungary’s subjugation under a series of authoritarian Empires – Autocratic Austrian, Nazi German and Soviet Russian, as well as under its own twenty-five-year-long Horthy régime (1919-44), has meant that it has only experienced brief ‘tides’ of ‘liberal’ government in those 150 years, all of a conservative-nationalist kind. Most recently, this was defined as ‘civil democracy’ in the 1989 Constitution. What has happened in the last three decades is that the ‘liberal democratic’ hegemony in Europe, whether expressed in its dominant Christian Democrat/ Conservative or Social Democratic parties has been threatened, for good or ill, by more radical populist movements on both the Right and Left. In Hungary, these have been almost exclusively on the Right, because the radical Left has failed to recover from the downfall of state socialism. With the centre-Left parties also in disarray and divided, FIDESZ-MPP has been able to control the political narrative and, having effectively subsumed the KDNP, has been able to dismiss all those to its left as ‘left-liberal’. The term is purely pejorative and propagandist. What if, we might ask, the Populist ‘wave’ of the last thirty years is now past its peak? What is Hungary’s democratic alternative, or are we to expect an indefinite continuance of one-party rule?

Issues of Identity: Nationhood or Nation-Statehood?:

-

What if the accession process has not really delivered on its promises, that of unifying Europe, bringing the West and the East together on fully equal terms? If so, then the resurgence of trust in one’s national identity is more readily understood. … There is nothing in the treaties banning nationhood.

The Brexit Divisions in Britain are clear: they are generational, national and regional.

We could empathise more easily with this view were it not for Schöpflin’s assumption that ‘Brexit’ was unquestionably fuelled by a certain sense of injured Englishness. His remark is typical of the stereotypical view of Britain which many Hungarians of a certain generation persist in recreating, quite erroneously. Questions of national identity are far more pluralistic and complex in western Europe in general, and especially in the United Kingdom, where two of the nations voted to ‘remain’ and two voted to ‘leave’. Equally, though, the Referendum vote in England was divided between North and South, and within the South between metropolitan and university towns on the one hand and ‘market’ towns on the other. The ‘third England’ of the North, like South Wales, contains many working-class people who feel themselves to be ‘injured’ not so much by a Brussels élite, but by a London one. The Scots, the Welsh, the Northern Irish and the Northern English are all finding their own voice, and deserve to be listened to, whether they voted ‘Remain’ or ‘Leave’. And Britain is not the only multi-national, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic nation-state in the western EU, as recent events in Spain have shown. Western Europeans are entirely sensitive to national identities; no more so than the Belgians. But these are not always as synonymous with ‘nation-statehood’ as they are among many of the East-Central nations.

Above: The Hungarian Opposition demonstrates on one of the main Danube bridges.

Hungarians with an understanding of their own history will have a clearer understanding of the complexities of multi-ethnic countries, but they frequently display more mono-cultural prejudices towards these issues, based on their more recent experiences as a smaller, land-locked, homogeneous population. They did not create this problem, of course, but the solution to it lies largely in their own hands. A more open attitude towards migrants, whether from Western Europe or from outside the EU might assist in this. Certainly, the younger, less ‘political’ citizens who have lived and work in the ‘West’ often return to Hungary with a more modern understanding and progressive attitude. The irony is, of course, due partly to this outward migration, Hungary is running short of workers, and the government is now, perhaps ironically, making itself unpopular by insisting that the ever-decreasing pool of workers must be prepared to work longer hours in order to satisfy the needs of German multi-nationals. In this regard, Schöpflin claims that:

The liberal hegemony was always weaker in Central Europe, supported by maybe ten per cent of voters (on a good day), so that is where the challenge to the hegemony emerged and the alternative was formulated, not least by FIDESZ. … In insisting that liberal free markets generate inequality, FIDESZ issued a warning that the free movement of capital and people had negative consequences for states on the semi-periphery. Equally, by blocking the migratory pressure on Europe in 2015, FIDESZ demonstrated that a small country could exercise agency even in the face of Europe-wide disapproval.

Above: Pro-EU Hungarians show their colours in Budapest.

Such may well be the case, but O’Sullivan tells us that even the ‘insurgent parties’ want to reform the EU rather than to leave or destroy it. Neither does Schöpflin, nor any of the other writers, tell us what we are to replace the ‘liberal hegemony’ in Europe with. Populist political parties seem, at present, to be little more than diverse protest movements and to lack any real ideological cohesion or coherence. They may certainly continue ‘pep up’ our political discourse and make it more accessible within nation-states and across frontiers, but history teaches us (Williams, 1983) that hegemonies can only be overthrown by creating an alternative predominant practice and consciousness. Until that happens, ‘liberal democracy’, with its diversity and versatility, is the only proven way we have of governing ourselves. In a recent article for The Guardian Weekly (30 November 2018), Natalie Nougayréde has observed that Viktor Orbán may not be as secure as he thinks, at least as far as FIDESZ’s relations with the EU. She accepts that he was comfortably re-elected earlier last year, the man who has dubbed himself as the “Christian” champion of “illiberal democracy”. Having come under strong criticism from the European People’s Party, the conservative alliance in the EU that his party belongs to. There is evidence, she claims, that FIDESZ will get kicked out of the mainstream group after the May 2019 European elections. Whether this happens or not, he was very publicly lambasted for his illiberalism at the EPP’s congress in Helsinki in November. Orbán’s image has been further tarnished by the so-called Gruevski Scandal, caused by the decision to grant political asylum to Macedonia’s disgraced former prime minister, criminally convicted for fraud and corruption in his own country. This led to a joke among Hungarian pro-democracy activists that “Orbán no longer seems to have a problem with criminal migrants”.

Some other signs of change across central Europe are worth paying careful attention to. Civil society activists are pushing are pushing back hard, and we should beware of caving into a simplistic narrative about the east of Europe being a homogeneous hotbed of authoritarianism with little effort of put into holding it in check. If this resistance leads to a turn in the political tide in central Europe in 2019, an entirely different picture could emerge on the continent. Nevertheless, the European elections in May 2019 may catch European electorates in a rebellious mood, even in the West. To adopt and adapt Mark Twain’s famous epithet, the rumours of the ‘strange’ death of liberal democracy in central Europe in general, and in Hungary in particular, may well have been greatly exaggerated. If anything, the last two hundred years of Hungarian history have demonstrated its resilience and the fact that, in progressive politics as in history, nothing is inevitable. The children of those who successfully fought for democracy in 1988-89 will have demonstrated that ‘truth’ and ‘decency’ can yet again be victorious. The oft-mentioned east-west gap within the EU would then need to be revisited. Looking at Hungary today, to paraphrase another bard, there appears to be too much protest and not enough practical politics, but Hungary is by no means alone in this. But Central European democrats know that they are in a fight for values, and what failure might cost them. As a consequence, they adapt their methods by reaching out to socially conservative parts of the population. Dissent is alive and well and, as in 1989, in working out its own salvation, the east may also help the west to save itself from the populist tide also currently engulfing it.

![referendum-ballot-box[1]](https://chandlerozconsultants.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/referendum-ballot-box1.jpg?w=1000)

Sources (Parts Four & Five):

Jon Henley, Matthius Rooduijn, Paul Lewis & Natalie Nougayréde (30/11/2018), ‘The New Populism’ in The Guardian Weekly. London: Guardian News & Media Ltd.

John O’Sullivan (ed.) (2018), Hungarian Review, Vol. IX, No. 5 (September) & No. 6 (November). Budapest: János Martonyi/ The Danube Institute.

Jeremy Isaacs & Taylor Downing (1998), Cold War. London: Bantam Press.

László Kontler (2009), A History of Hungary. Budapest: Atlantisz Publishing House.

Lobenwein Norbert (2009), a rendszerváltás pillanatai, ’89-09. Budapest: VOLT Produkció

Douglas Murray (2018), The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity, Islam. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Raymond Williams (1988), Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture & Society. London: Fontana

John Simpson (1990), Despatches from the Barricades. London: Hutchinson.

Marc J Susser (ed.) (2007), The United States & Hungary: Paths of Diplomacy, 1848-2006. Washington: Department of State Publication (Bureau of Public Affairs).

Posted January 5, 2019 by AngloMagyarMedia in Affluence, Africa, American History & Politics, anti-Communist, Anti-racism, anti-Semitism, Assimilation, Austria-Hungary, Balkan Crises, Baltic States, Baptists, BBC, Belgium, Berlin, Bible, Britain, British history, Britons, Brussels, Christian Faith, Christianity, Civil Rights, Civilization, Cold War, Colonisation, Commemoration, Communism, Compromise, democracy, devolution, Discourse Analysis, Economics, Egalitarianism, Egypt, Empire, Europe, European Union, Family, Fertility, France, Genocide, German Reunification, Germany, Holocaust, homosexuality, Humanism, Humanitarianism, Humanities, Hungarian History, Hungary, Immigration, Imperialism, Integration, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Jews, Journalism, liberal democracy, liberalism, Marriage, marriage 'bar', Marxism, Maternity, Mediterranean, Memorial, Middle East, Migration, Monuments, morality, Mythology, Narrative, nationalism, Nationality, NATO, Population, populism, Poverty, Racism, Reconciliation, Refugees, Remembrance, Revolution, Scotland, Second World War, Serbia, Socialist, south Wales, Statehood, Switzerland, Syria, Technology, terror, terrorism, tyranny, Unemployment, United Nations, USA, World War Two, xenophobia, Yugoslavia

Tagged with 'Ano' Party, 'Brothers of Italy', 'Freunderlwirtschaft', 'illiberalism', 'Islamic' terrorism, 'The Economist', 1956, AfD, Alexis Tsipras, Angela Merkel, apparatchiks, Austria, Barroso, Báky Coup, Botond Gaál, Brexit, Brussels, Budapest, Business, Christianity, Croatia, culture, current-events, Damascene Conversion, Danube Institute, Denmark, Douglas Murray, Dublin procedures, dystopia, ECJ, EEA, England, Eurocrats, Euroscepticism, Faith, Ferenc Gyurcsány, Ferenc Koszorús, FIDESZ-MPP, Geert Wilder, Gellért Hill, George Soros, George W Bush, Giorgi Meloni, Greece, Green Left, György Schöpflin, Habsburg Solution, health, hegemony, Hezbollah, History, Holocaust, Horthy, housing, Hungarian Review, Hurricane Katrina, IMF, Indian subcontinent, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Islam, Islamaphobia, Italy, Jan Kavan, Jaraslaw Kaczynski, József Antall, Jean-Claude Juncker, John O'Sullivan, Jon Henley, Judith Sargentini, Karl Popper, KDNP (Christian Democrats), Laura Bush, Law and Justice Party, László Csaba, Lenin, Lesbos, liberty, majoritarianism, Martin Mejstrik, Millennium, Milos Zeman, NATO, neo-liberalism, Paul Lendvai, Paul Lewis, Péter Ákos Bod, Péter Eszsterházy, Philipp Ter, Podemos, Poland, politics, Prague, PVV, Raymond Williams, Rákosi, religion, Risorgimento, Robert Fico, Rouhani, same-sex marriage, Sargentini Report, Schengen Agreement, Serbia, sexual preference, Slovakia, Slovenia, Social Democrats, society, Soviet Union, Steve Bannon, Strasbourg, Sweden, Swiss People's Party, Syriza, Taszár, the Guardian, Thomas Piketty, Trade, Transylvania, UN, USA, Vaclav Klaus, Viktor Orbán, Visegrád group

The Decade of Extremes – Punks, Skinheads & Hooligans:

The 1970s was an extreme decade; the extreme left and extreme right were reflected even in its music. Much of what happened in British music and fashion during the seventies was driven by the straightforward need to adopt and then outpace what had happened the day before. The ‘Mods’ and ‘Hippies’ of the sixties and early seventies were replaced by the first ‘skinheads’, though in the course there were ‘Ziggy Stardust’ followers of David Bowie who would bring androgyny and excess to the pavements and even to the playground. Leather-bound punks found a way of offending the older rockers; New Romantics with eye-liner and quiffs challenged the ‘Goths’. Flared jeans and then baggy trousers were suddenly ‘in’ and then just as quickly disappeared. Shoes, shirts, haircuts, mutated and competed. For much of this time, the game didn’t mean anything outside its own rhetoric. One minute it was there, the next it had gone. Exactly the same can be said of musical fads, the way that Soul was picked up in Northern clubs from Wigan to Blackpool to Manchester, the struggle between the concept albums of the art-house bands and the arrival of punkier noises from New York in the mid-seventies, the dance crazes that came and went. Like fashion, musical styles began to break up and head in many directions in the period, coexisting as rival subcultures across the country. Rock and roll was not dead, as Don McLean suggested in American Pie, when heavy metal and punk-rock arrived, nor was Motown, when reggae and ska arrived. The Rolling Stones and Yes carried on oblivious to the arrivals of the Sex Pistols and the Clash.

In this stylistic and musical chaos, running from the early seventies to the ‘noughties’, there were moments and themes which stuck out. Yet from 1974 until the end of 1978, living standards, which had doubled since the fifties, actually went into decline. The long boom for the working-classes was over. British pop had been invented during the optimistic years of 1958-68 when the economy was most of the time buoyant and evolving at its fastest and most creative spirit. The mood had turned in the years 1968-73, towards fantasy and escapism, as unemployment arrived and the world seemed bleaker and more confusing. This second phase involved the sci-fi glamour of David Bowie and the gothic mysticism of the ‘heavy metal’ bad-boy bands like Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin. The picture below shows Robert Plant and Jimmy Page on stage in Chicago during their 1977 North American tour (Page is playing the double-neck Gibson used for their classic song, Stairway to Heaven).

The years 1974-79 were a period of deep political disillusion, with strains that seemed to tear at the unity of the United Kingdom: First there was Irish terrorism on the mainland, when in October two IRA bombs exploded in Guildford, followed by two more in Birmingham. Like many others, I will never forget the horrendous scenes in England’s second city the day after the Tavern in the Town was blasted. This was followed by a rise in racial tension and widespread industrial mayhem. The optimism which had helped to fuel the flowering of popular culture in the sixties was suddenly exhausted, so it is perhaps not a coincidence that this period was a darker time in music and fashion, a nightmare inversion of the sixties dream. In sport, the mid-seventies saw the invention of the ‘football hooligan’.

This led on to serious problems for football grounds around the country, as the government introduced the 1975 Safety of Sports Grounds Act. The home of Wolverhampton Wanderers, ‘Molineux’, had remained virtually unchanged since 1939, apart from the Molineux Street Stand, which had been made all-seater. But this distinctive seven-gabled stand (seen in the picture above) was deemed unsafe according to the act’s regulations and therefore had to be replaced. Architects were commissioned to replace the old stand, with its unique shape, with a new stand. To do this, the club had to purchase the remaining late Victorian terraced houses in Molineux Street and North Street which pre-dated the football ground, and all seventy-one of them were demolished to clear space for the new two million pound stand to be built at the rear of the old stand. The ‘new’ stand, with its 9,348 seats and forty-two executive boxes, was officially opened on 25 August 1979. Once the debris of the old stand was moved away, the front row of seats were almost a hundred feet from the pitch. From the back row, the game was so far away that it had to be reported by rumour! Also, throughout this period, the team needed strengthening.

In the 1974-75 season, Wolves won the League Cup, beating star-studded Manchester City 2-1 at Wembley, and nearly reversed a 4-1 deficit against FC Porto in the UEFA Cup with an exciting 3-1 home victory. Wolves finished in a respectable twelfth place in the League. But at the end of the season, the team’s talisman centre-forward, Belfast-born Derek Dougan, decided to retire. He had joined the club in 1967, becoming an instant hit with the Wolves fans when he scored a hat-trick on his home debut, and netting nine times in eleven games to help Wolves win promotion that season. He was a charismatic man, a thrilling player and one of the best headers of the ball ever seen. He also held the office of Chairman of the PFA (Professional Football Association) and in 1971/72 forged a highly successful striking partnership with John Richards. Their first season together produced a forty League and UEFA Cup goals, twenty-four the Doog and sixteen for Richards. In 1972/73, they shared fifty-three goals in all competitions, Richards getting thirty-six and Dougan seventeen. In two and a half seasons of their partnership, the duo scored a total of 125 goals in 127 games. Derek Dougan signed off at Molineux on Saturday, 26th April 1975. In his nine years at Wolves, Dougan made 323 appearances and scored 123 goals, including five hat-tricks. He also won 43 caps for Northern Ireland, many of them alongside the great George Best, who himself had been a Wolves fan as a teenager.

Above: Derek Dougan in 1974/75, the season he retired.

Wolves had always been considered ‘too good to go down’ after their 1967 promotion but following the departure of ‘the Doog’ they embarked on a run to obscurity, finishing twentieth at the end of the 1975/76 season, resulting in their relegation to the second tier of English football. Worse still, early in 1976, Wolves’ fabulously speedy left-winger, Dave Wagstaffe, was transferred to Blackburn Rovers. In his twelve years at Molineux, ‘Waggy’ had scored thirty-one goals, including a ‘screamer’ in a 5-1 defeat of Arsenal, in over four hundred appearances. In time-honoured fashion, the majority of fans wanted money to be spent on new players, not on a stand of such huge proportions. Although Wolves returned to the League’s top flight at the end of the next season, they were still not good enough to finish in the top half of the division. More departures of longstanding stalwarts followed, including that of captain Mike Bailey, Frank Munro and goalkeeper Phil Parkes. The East Midlands clubs took over in the spotlight, first Derby County and then Nottingham Forest, who won the European Cup in 1979, to make Brian Clough’s dream a reality. Before the 1979-80 season kicked off, Wolves’ manager John Barnwell produced a stroke of genius by signing Emlyn Hughes from Liverpool to be his captain. Then he sold Steve Daley to Manchester City for close to 1.5 million pounds, and three days later signed Andy Gray from Aston Villa for a similar amount. Daley (pictured below in action against FC Porto) was a versatile, attacking midfielder who played in 218 senior games for Wolves, scoring a total of forty-three goals. Andy Gray scored on his debut for Wolves and went on to get another eleven League goals, one behind John Richards. He also scored in the League Cup Final in March to give Wolves a 1-0 victory over Nottingham Forest, and a place in the next season’s UEFA Cup.

John Richards continued to play on into the 1980s for Wolves. According to John Shipley, he was a true Wolves legend, a player who would have graced any of Wolves’ Championship-winning teams. He was also a true gentleman, in the Billy Wright mould. He had signed for Wolves in 1967, turning professional two years later. I remember seeing him make his first-team debut at the Hawthorns against West Bromwich Albion on 28 February 1970, scoring alongside Derek Dougan in a 3-3 draw. They both played and scored in the 3-1 away victory against Fiorentina the following May. Richards went on to score 194 goals in 486 appearances, a goalscoring record which stood for ten years. He won only one full England cap, due mainly to injury.

Like me, the entertainer Frank Skinner grew up on the fictional cartoon comic strip hero, Roy of the Rovers. Of course, when – as in his case – you support a real-life team that never wins anything, like West Bromwich Albion, it’s nice to follow a fictional team that scoops the lot. Melchester Rovers were his mythical alternative, and following them came with none of the attendant guilt that comes with slyly supporting another club, say Liverpool in the seventies. They were his ‘dream team’ with a cabinet of silverware and a true superstar-striker as player-manager. The 1970s were a time when both life and the beautiful game seemed far less complicated for teenagers. Watching it on TV, we would frequently hear a commentator say “this is real Roy of the Rovers Stuff”. What they usually meant was that there was one player on the pitch was doing something remarkable, unbelievable or against all odds. But even in the fictional pages, Roy had to confront the dark realities of hooligans among his own fans, and do battle with it in his own way, as the following frames show:

Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren turned from creating beatnik jumpers to the ripped T-shirts and bondage gear of punk: the Sex Pistols portrayed themselves as a kind of anti-Beatles. Westwood was in many ways the perfect inheritor of Quant’s role of a dozen years earlier. Like Quant, she was brought up to make her own clothes and came through art college. She was similarly interested in the liberating power of clothes, setting herself up in a Kings Road shop which first needed to be braved before it could be patronised. Yet she was also very different from Quant, in that she had first mixed and matched to create a style of her own at the Manchester branch of C&A and claimed that her work was rooted in English tailoring. Her vision of fashion was anything but simple and uncluttered. According to Andrew Marr, it was a magpie, rip-it-up and make it new assault on the history of coiture, postmodern by contrast with straightforward thoroughly modern designs of Quant. The latter’s vision had been essentially optimistic – easy to wear, clean-looking clothes for free and liberated women. Westwood’s vision was darker and more pessimistic. Her clothes were to be worn like armour in a street battle with authority and repression, in an England of flashers and perverts. Malcolm McLaren formed the Sex Pistols in December 1975, with Steve Jones, Paul Cook, John Lydon and Glen Matlock making up a foursome which was anything but ‘fab’. Pockmarked, sneering, spitting, spikey-haired and exuding violence, they dutifully performed the essential duty of shocking a nation which was still too easily shocked. The handful of good songs they recorded have a leaping energy which did take the rock establishment by storm, but their juvenile antics soon became embarrassing. They played a series of increasingly wild gigs and made juvenile political attacks in songs such as ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and, in the year of the Silver Jubilee (1977), ‘God Save the Queen. Jim Callaghan could be accused of many things, but presiding over a ‘fascist régime’ was surely not one of them.