Archive for the ‘Martin Luther’ Category

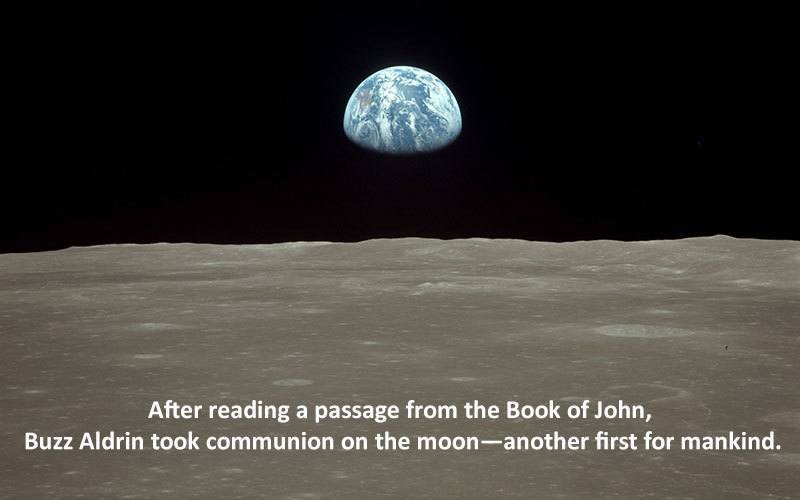

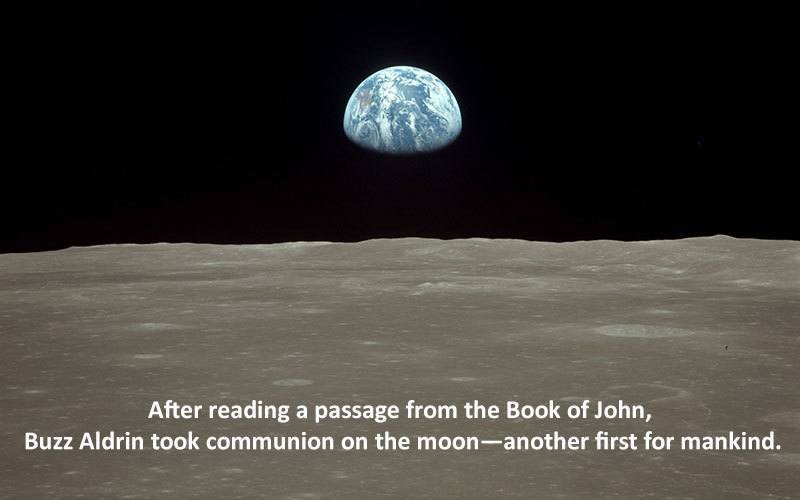

Below: The picture of earth from the Moon, July 1969.

On 20 July 1969 human beings stepped onto the surface of the moon, in one giant leap for mankind.

A Giant Leap of Imagination:

I was just twelve years old when the Apollo 11 lunar module landed on the moon. I remember the event very clearly, being allowed to stay up to watch on our small, black and white television. The whole event was in black and white for everyone on earth, as colour television transmissions did not begin until the following year when we went round to a friend’s house to watch the Football World Cup via satellite from Mexico.

I was just twelve years old when the Apollo 11 lunar module landed on the moon. I remember the event very clearly, being allowed to stay up to watch on our small, black and white television. The whole event was in black and white for everyone on earth, as colour television transmissions did not begin until the following year when we went round to a friend’s house to watch the Football World Cup via satellite from Mexico.

Looking back over those fifty years, it’s interesting to see how much of popular culture on both sides of the Atlantic has been influenced by that event, and the subsequent two Apollo landings of the seventies. Before 1969, most classical compositions and popular song lyrics referenced the moon and the stars in the romantic terms of ‘moonlight’ and ‘Stardust’, even Sinatra’s ‘Fly me to the Moon’. These metaphors continued afterwards, but they were joined by a growing genre of songs about ‘rocketmen’ and space and time exploration which had begun in the early sixties with TV series like ‘Fireball XL-5’, ‘Dr Who’ and ‘Star Trek’.

Looking back over those fifty years, it’s interesting to see how much of popular culture on both sides of the Atlantic has been influenced by that event, and the subsequent two Apollo landings of the seventies. Before 1969, most classical compositions and popular song lyrics referenced the moon and the stars in the romantic terms of ‘moonlight’ and ‘Stardust’, even Sinatra’s ‘Fly me to the Moon’. These metaphors continued afterwards, but they were joined by a growing genre of songs about ‘rocketmen’ and space and time exploration which had begun in the early sixties with TV series like ‘Fireball XL-5’, ‘Dr Who’ and ‘Star Trek’.

Gradually, Science Fiction literature and films took us beyond cartoonish ‘superhero’ representations of space and HG Wells’ early novels until, by the time I went to University, ‘Star Wars’ had literally exploded onto the big screens and was taking us truly into a new dimension, at least in our imaginations.

The Dawning of a New Age?

The ‘Age of Aquarius’ had begun on earth as well, with rock musicals, themed albums and concerts, and ‘mushrooming’ festivals under the stars providing the soundtrack and backdrop to the broadening of minds and horizons. Those ‘in authority’ were not at all tolerant of the means used by some to help broaden these horizons and, in those days, these mass encampments were not always seen as welcome additions to the rural landscape and soundscape. Many evangelical Christians were suspicious of the ‘New Age’ mysticism embraced by the Beatles, the outrageous costumes and make-up of David Bowie and Elton John, and the heavy rock music of a series of bands who made use of provocative satanic titles and emblems, like ‘Black Sabbath’. But some, like Larry Norman and ‘The Sheep’, decided to produce their own parallel ‘Christian Rock’ culture. The first Christian ‘Arts’ Greenbelt Festival was held on a pig farm just outside the village of Charsfield near Woodbridge, Suffolk over the August 1974 bank holiday weekend.

My Christian friends and I, having already seen the musical Lonesome Stone in Birmingham, made the trek across the country to discover more of this genre. Local fears concerning the festival in the weeks running up to it proved to be unfounded, but the festival didn’t return to the venue. We, on the other hand, were excited and enthused by what we saw and heard.

My Christian friends and I, having already seen the musical Lonesome Stone in Birmingham, made the trek across the country to discover more of this genre. Local fears concerning the festival in the weeks running up to it proved to be unfounded, but the festival didn’t return to the venue. We, on the other hand, were excited and enthused by what we saw and heard.

The ‘mantra’ we repeated when we got home to our churches was William Booth’s question, voiced by Larry, Why should the devil get all the best tunes? We wrote and performed our own rock musical, James (a dramatisation of the Book of James) touring it around the Baptist churches in west Birmingham, a different form of evangelism from that of Mary Whitehouse and her ‘Festival of Light’. One of our favourite songs was Alpha and Omega:

He’s the Alpha and Omega,

The Beginning and the End,

The first and last,

Our eternal friend.

Another of their ‘millenarian’ songs, Multitudes, also emphasised the importance of the Day of the Lord, which seemed to chime in well with the ‘nuclear age’ and the Eve of Destruction songs of Bob Dylan and Barry McGuire, among others.

Sun, Moon and Stars in their Courses Above:

But though we began to sing new songs, much of this revivalist spirit still owed its origins and source of inspiration to the 1954 North London crusade of Billy Graham, and the hymns associated with it. Great is Thy Faithfulness, written in the USA in the early 1920s, really owes its popularity in Britain to its use by the Billy Graham Crusade (pictured right).

It took some time to for it to find its way into the hymnbooks in Britain, but it now stands high in the ‘hit parade’, ranking fourth in the 2002 BBC Songs of Praise poll. It has much in common with our other hymn, How Great Thou Art, which was the most popular and probably still is, thanks to recent recordings. Both hail from the early part of the twentieth century and both display a strong emphasis on creation and nature, which have become dominating discourses by the early part of the twenty-first century.

Great is Thy Faithfulness is the work of Thomas Chisholm (1866-1960), a devout Methodist from Kentucky who worked successively as a journalist, a school teacher and a life-insurance agent before becoming ordained. He wrote the verses in 1923 and later reflected that there were no special circumstances surrounding their writing and that he was simply expressing his impressions of God’s faithfulness as recounted in the Bible. Yet, as Tom White has written recently in his book on Paul, our ‘justification’ as Christians is not the result of our own ‘little faith’ so much as the great faithfulness of God as revealed in his son, Jesus Christ. Chisholm sent his poem, along with several other poems, to his friend and collaborator William Runyan (1870-1957), a fellow Methodist who achieved considerable fame in the USA as a composer of sacred music and gospel songs.

Its early popularity in the USA was partly the result of its promotion by Dr Will Houghton, president of the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago (pictured right), who used it frequently both in the services he took and on his radio broadcasts on WMBI. George Beverly Shea, first as a singer on the station’s early morning programme, Hymns from the Chapel, and then as the lead singer at Graham’s rallies, also helped to popularise the hymn across America.

Its early popularity in the USA was partly the result of its promotion by Dr Will Houghton, president of the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago (pictured right), who used it frequently both in the services he took and on his radio broadcasts on WMBI. George Beverly Shea, first as a singer on the station’s early morning programme, Hymns from the Chapel, and then as the lead singer at Graham’s rallies, also helped to popularise the hymn across America.

The opening verse is based directly on scriptural affirmations about God. Lamentations 3.22 and 33 proclaim that His compassions fail not; they are new every morning: great is thy faithfulness, and James 1.17 declares that every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, and cometh down from the Father of lights, with whom there is no variableness, neither shadow of turning:

Great is thy faithfulness, O God my Father,

there is no shadow of turning with thee;

thou changest not, thy compassions they fail not,

as thou hast been, thou for ever wilt be!

Great is thy faithfulness!

Great is thy faithfulness!

Morning by morning new mercies I see;

all I have needed thy hand hath provided –

great is thy faithfulness, Lord unto me!

Summer and winter, and spring-time and harvest,

sun, moon and stars in their courses above,

join with all nature in manifold witness

to thy great faithfulness, mercy and love.

Inspired by a Summer Evening in Sweden:

The second verse places the individual Christian in the context of the wider creation and emphasises the interdependence of the whole created order under its creator. This is the theme which is taken up in How Great Thou Art.

According to the 2002 Songs of Praise poll, this is Britain’s favourite hymn, and readers of the Catholic weekly, The Tablet, voted it third in their list of top ten hymns in 2004. Like Great is Thy Faithfulness, it owes much of its popularity to its extensive use in the Billy Graham crusades of the 1950s. But prior to that, the hymn owes its origins to a trail leading from Sweden to Britain via central-eastern Europe. The words in English are a translation of a Swedish poem, O store Gud, by Carl Boberg (1859-1940), an evangelist, journalist and for fifteen years a member of Sweden’s parliament. He was born the son of a shipyard worker on the south-east coast of Sweden. He came to faith at the age of nineteen and went to Bible School Kristinehamn. He returned to his native town of Monsteras as a preacher and it was there in 1886 that he wrote his nine-verse poem, inspired to praise God’s greatness one summer evening while looking across the calm waters of the inlet. A rainbow had formed, following a storm in the afternoon, and a church bell was tolling in the distance. Translated literally into English, the first verse of his poem reads:

O Thou great God! When I the world consider

Which Thou hast made by Thine almighty Word;

And how the web of life Thy wisdom guideth,

And all creation feedeth at Thy board:

Then doth my soul burst forth in song of praise:

O Thou great God! O Thou great God!

Boberg’s verses were set to music in 1891 and appeared in several Swedish hymnbooks around the turn of the century. An English translation was published in 1925 under the title O Mighty God, but never really caught on. Earlier, in 1912, a Russian version by Ivan Prokhanoff had appeared. This was almost certainly made from a German translation of the original Swedish hymn. The English translation was the work of British missionary and evangelist, Stuart K Hine (1899-1989), who heard it being sung in Russian in western Ukraine, where he had gone in 1923. After singing the hymn in Russian for many years, Hine translated the first three verses while continuing his missionary work in the Carpathian mountains in the 1930s. The scenery there inspired his second verse which draws little from Boberg’s original poem while remaining true to its general spirit of wonder at God’s creation:

O Lord my God, when I in awesome wonder

Consider all the works Thy hand hath made,

I see the stars, I hear the mighty thunder,

Thy power throughout the universe displayed:

Then sings my soul, my saviour God, to Thee,

How great Thou art! How great Thou art!

(x 2)

When through the woods and forest glades I wander

And hear the birds sing sweetly in the trees:

When I look down from lofty mountain grandeur,

And hear the brook, and feel the gentle breeze;

When are we Going to go Home?

Stuart Hine wrote the fourth verse of his hymn when he was back in Britain in 1948. In that year more than a hundred thousand refugees from Eastern Europe streamed into the United Kingdom. The question uppermost in their minds was When are we going home? In an essay on the history of the hymn, Hine wrote:

What better message for the homeless than that of the One who went to prepare a place for the ‘displaced’, of the God who invites into his own home those who will come to him through Christ.

Contrasting with a third verse which is about Christ’s ‘bearing’ of our individual burdens of sin on the cross, the final verse is about our places among the multitudes on the ‘last day’, just like the mass of homeless refugees finding a temporary home in Britain:

When Christ shall come with shout of acclamation

And take me home – what joy shall fill my heart!

Then shall I bow in humble adoration

And there proclaim, my God, how great Thou art!

Seventy years ago, Stuart Hine published both the Russian and the English versions of the hymn in his gospel magazine Grace and Peace in 1949. O Lord My God rapidly caught on in evangelical circles both in Britain and the UK, as well as in Eastern Europe, despite the oppression of the churches by the Soviet-style communist régimes which were taking control of the states where the hymn was first heard. The Hungarian Baptist Hymnbook contains a translation by Balázs Déri (born in 1954):

The hymn has been regularly sung in Hungarian Baptist Churches in recent decades, but it’s popularity probably stems, not so much to its sub-Carpathian origins, but to George Beverly Shea (below), the leading vocalist in Billy Graham’s evangelistic team, who was given a copy of it during the London crusade at the Haringey Arena in 1954. It became a favourite of Shea, the team’s choir director, Cliff Barrows and Graham himself, who wrote of it:

The reason I liked “How Great Thou Art!” was because it glorified God: it turned a Christian’s eyes toward God rather than upon himself, as so many songs do.

The hymn is still sung, universally, to the beautiful Swedish folk-melody to which Boberg’s original verses were set in 1891. It was the tune that I first fell in love with as a boy soprano when my Baptist minister father introduced my contralto sister and me to the hymn as our entry as a duet into the west Birmingham Baptists’ Eisteddfod (Festival of Arts), which was held during the same year as the lunar landing, my first year of secondary school (1968-69). Looking back, I’m convinced that it was my father’s involvement in the Billy Graham campaign as a young minister in Coventry which encouraged his love of the hymn. When it was sung by the congregation at his second church in Birmingham, he would always provide his own accompaniment on the piano, ensuring that the organist and the congregation did not ‘drag’ the tune and that it kept to a ‘Moody’ style, as in the days of the Graham Crusade.

Its reference to ‘the stars’ as evidence of the works thy hand hath made, inserted by Hine, anticipated the sense of awe and wonder experienced by the astronauts onboard the Apollo missions. Both the words and the music have continued to captivate soloists and congregations alike. Elvis Presley released his version of it, and more recently my favourite Welsh singers, Bryn Terfel, Katherine Jenkins and Aled Jones have also recorded their renditions. It was certainly a favourite of the Baptist congregations I regularly joined during my days as a student in Wales in the seventies, though they had many wonderful tunes of their own, including Hyfrydol, meaning just that. Most recently, the Mormon group, The Piano Guys recorded their ‘crossover’ instrumental version of it on their Wonders album, appropriately combining it with Ennio Morricone’s haunting composition for the film, The Mission, with Jon Schmidt at the piano and Steven Sharp Nelson on cello.

Alpha & Omega – In the Beginning and At the End:

For the astronauts on the Apollo 11 Mission, the landing was a profoundly spiritual event, according to their own testimony. They read from the gospel and even celebrated communion (see below). On Sunday (14th July 2019), a service from Leicester Cathedral to mark the 50th anniversary of the Moon landings was broadcast on the BBC under the title The Heavens are telling the glory of God. The service celebrated the achievement of the Apollo 11 Mission and asked whether the ‘giant leap’ has made us more, or less aware of our own human limitations and of our longing for God. It was led by the Dean of Leicester, the Very Reverend David Monteith, with contributions from staff at the National Space Centre and Christians involved in Astrophysics and Space Science. The Cathedral Choir led the congregation in hymns including Great Is Thy Faithfulness and The Servant King.

The Servant King is one of many worship songs written by Graham Kendrick (born 1950), the son of a Baptist pastor, M. D. Kendrick. Graham Kendrick (pictured right, performing in 2019) began his songwriting career in the late 1960s when he underwent a profound religious experience at teacher-training college. This set him off on his itinerant ministry as a musician, hymn-writer and worship-leader. After working in full-time evangelism for Youth for Christ, with which I had been involved in Birmingham, in 1984 he decided to focus all his energies on congregational worship music. He has also become closely associated with the Ichthus Fellowship, one of the largest and most dynamic of the new house churches to emerge from the charismatic revival.

The Servant King is one of many worship songs written by Graham Kendrick (born 1950), the son of a Baptist pastor, M. D. Kendrick. Graham Kendrick (pictured right, performing in 2019) began his songwriting career in the late 1960s when he underwent a profound religious experience at teacher-training college. This set him off on his itinerant ministry as a musician, hymn-writer and worship-leader. After working in full-time evangelism for Youth for Christ, with which I had been involved in Birmingham, in 1984 he decided to focus all his energies on congregational worship music. He has also become closely associated with the Ichthus Fellowship, one of the largest and most dynamic of the new house churches to emerge from the charismatic revival.

His most successful musical accomplishment is his authorship of the song, Shine, Jesus, Shine, which is among the most widely heard songs in contemporary Christian worship worldwide. His other songs, like Meekness and Majesty, have been primarily used by worshippers in Britain. Although now best known as a worship leader and writer of worship songs, Graham Kendrick began his career as a member of the Christian beat group Whispers of Truth (formerly the Forerunners). Later, he began working as a solo concert performer and recording artist in the singer/songwriter tradition. He was closely associated with the organisation Musical Gospel Outreach and recorded several albums for their record labels. On the first, Footsteps on the Sea, released in 1972, he worked with the virtuoso guitarist Gordon Giltrap. In 1975 and 1976, he was one of the contributing artists at the second and third Greenbelt Arts Festival at Odell Castle in Bedfordshire. I was present at both of these, and also attended the fortieth, a much bigger event, at Cheltenham (see below) in 2013 where I watched him perform again.

Until the advent of Shine Jesus Shine, The Servant King was Graham Kendrick’s most popular song and is still one of the top 10 songs in the CCL (Church Copyright Licence). It was also voted 37th in the 2002 Songs of Praise poll. Written to reflect the theme for the 1984 Spring Harvest Bible teaching event and the Greenbelt Festival later that year, it illustrates Graham’s willingness to research a theme using concordances, commentaries and other biblical research tools. He found the theme very inspiring:

It was a challenge to explore the vision of Christ as the servant who would wash the disciples’ feet but who was also the Creator of the universe.

He wrote both the words and the tune, as with virtually all of his songs, first picking out the tune on the piano at home. It is a short and simple hymn which yet has a wonderful theological sweep and depth. The song is based on an incarnational root and is one of the few songs I know that can be used in worship at Christmas and Easter, and at any time between the two as a call to renewed commitment and discipleship. Its opening line is very reminiscent of Martin Luther’s Christmas hymn, From Heaven Above to Earth I Come, and it goes on to cover the agony of Jesus in the garden of tears and his crucifixion and calls on us to serve him as he did his disciples. I remember a Good Friday ‘service of nails’ in which it featured. It begins with the incarnation – From heaven you came, helpless babe – and progresses to one of Graham’s most poignant lines: Hands that flung stars into space to cruel nails surrendered:

From heaven you came helpless babe

Entered our world, your glory veiled

Not to be served but to serve

And give Your life that we might live

This is our God, the Servant King,

He calls us now to follow him,

To bring our lives as a daily offering

Of Worship to the Servant King.

Come see His hands and His feet

The scars that speak of sacrifice

Hands that flung stars into space

To cruel nails surrendered

It reminds us of the timeless nature of the acts of creation, incarnation and reconciliation, and of the inextricable link between them. Jesus is Alpha and Omega, his hands flinging stars into space, but then enters human time as a helpless babe, with the same hands being used to pin him to the cruel Roman gibbet in a once and for all act of atonement of the whole created order, fallen and the restored. For me, the final lines are among the most poignant and poetic of any hymn or worship song. It is also worthy to stand alongside the great classics of evangelical hymnody by Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley. It is more of a contemporary hymn in this classical tradition than a worship-song. It is addressed to Christ, and both its verses and chorus are cast in strophic, metrical form. Kendrick’s tune is also an unmistakably modern idiom and the resulting hymn does not ‘dumb down’ in terms of its theological subtlety and profundity. Neither does it suffer from the excessive individualism of so many contemporary worship songs. Like Great is Thy Faithfulness and O Lord My God, When I in Awesome Wonder, The Servant King places the paradox of greatness and sacrifice at the centre of the Christian religion as a truly universal faith and practice. Like his Meekness and Majesty, this hymn effectively points up the central paradox that Jesus is both king and servant, priest and victim: the one whose weakness is strength and who conquers through love.

Sources:

Ian Bradley (2005), The Daily Telegraph Book of Hymns. London: Continuum.

Wikipedia articles and pictures (Apollo 11).

Greenbelt memorabilia & DVD.

The Piano Guys, Wonders, album artwork, 2014. THEPIANOGUYS.COM.

Luther’s Last Decade and His Legacy:

In the final decade of his life, Luther became even more bitter in his attitude towards the papists. He was denied another public hearing such as those at Worms and Speyer, and he managed to avoid the martyrdom which came to other reformers, whether at the stake or, in the case of Zwingli, in battle (at Kappel in 1531). He compensated by hurling vitriol at the papacy and the Roman Curia. Towards the end of his life, he issued an illustrated tract with outrageously vulgar cartoons. In all of this, he was utterly unrestrained. The Holy Roman Empire was a constitutional monarchy, and the emperor had sworn at his coronation that no German subject should be outlawed unheard and uncondemned. Although this clause had not yet invoked to protect a monk accused of heresy, yet when princes and electors came to be involved the case was altered. If Charles V were faithless to that oath, then he might be resisted even in arms by the lower magistrates. The formula thus suggested by the jurists to Luther was destined to have a very wide an extended vogue. The Lutherans employed it only until they gained legal recognition at Augsburg in 1555. Thereafter the Calvinists took up the slogan and equated the lower magistrates with the lesser nobility in France. Later historians were accustomed to regard Lutheranism as politically subservient and Calvinism as intransigent, but the origin of this doctrine was in the Lutheran soil.

Martin Luther was made for the ministry. During his last years, he continued to attend faithfully to all the obligations of the university and his parish. To the end he was preaching, lecturing, counselling and writing. At the end of his life, he was in such a panic of disgust because the young women at Wittenberg were wearing low necks that he left home declaring that he would not return. His physician brought him back, but then came a request from the counts of Mansfeld for a mediator in a dispute. Melanchthon was too sick to go, and though Luther was also very ill, he went, reconciled the counts and died on the way home.

His later years should not, however, be written off as the splutterings of a dying flame. If in his polemical tracts he was at times savage and course, in the works which really counted in the cannon of his life’s endeavour he grew constantly in maturity and artistic creativity. Improvements in the translation of the Bible continued to the very end. The sermons and biblical commentaries reached superb heights. Many of the passages quoted to illustrate Luther’s religious and ethical principles are also from this later period.

When historians and theologians come to assess his legacy, there are three areas which naturally suggest themselves. The first is his contribution to his own country. He called himself the German prophet, saying that against the papist assess he must assume so presumptuous a title and he addressed himself to his beloved Germans. The claim has been made frequently that no individual did so much to fashion the character of the German people. He shared their passion for music and their language was greatly influenced by his writings, not least by his translation of the Bible. His reformation also profoundly affected the ordinary German family home. Roland Bainton (1950) commented:

Economics went the way of capitalism and politics the way of absolutism, but the home took on that quality of affectionate and godly patriarchalism which Luther had set as the pattern of his own household.

Luther’s most profound impact was in their religion, of course. His sermons were read to the congregations, his liturgy was sung, his catechism was rehearsed by the father of the household, his Bible cheered the faint-hearted and consoled the dying. By contrast, no single Englishman had the range of Luther. The Bible translation was largely the work of Tyndale, the prayer-book was that of Cranmer, the Catechism of the Westminster Divines. The style of sermons followed Latimer’s example and the hymn book was owed much to George Herbert from the beginning. Luther, therefore, did the work of five Englishmen, and for the sheer richness and exuberance of vocabulary and mastery of style, his use of German can only be compared with Shakespeare’s use of English.

In the second great area of influence, that of the Church, Luther’s influence extended far beyond his native land, as is shown below. In addition to his influence in Germany, Switzerland, Hungary and England, Lutheranism took possession of virtually the whole of Scandinavia. His movement gave the impetus that sometimes launched and sometimes gently encouraged the establishment of other varieties of Protestantism. Catholicism also owes much to him. It is often said that had Luther not appeared, an Erasmian reform would have triumphed, or at any rate a reform after the Spanish model. All this is, of course, conjectural, but it is obvious that the Catholic Church received a tremendous shock from the Lutheran Reformation and a terrific urge to reform after its own pattern.

The third area is the one which mattered most to Luther, that of religion itself. In his religion, he was a Hebrew, Paul the Jew, not a Greek fancying gods and goddesses in a pantheon in which Christ was given a niche. The God of Luther, as of Moses, was the God who inhabits the storm clouds and rides on the wings of the wind. He is a God of majesty and power, inscrutable, terrifying, devastating, and consuming in his anger. Yet he is all merciful too, like as a father pitieth his children, so the Lord…

Lutherans, Calvinists, Anglicans and Pacifists:

The movement initiated by Luther soon spread throughout Germany. Luther provided its chief source of energy and vision until his death in 1546. Once Luther had passed from the scene, a period of bitter theological warfare occurred within Protestantism. There was controversy over such matters as the difference between ‘justification’ and ‘sanctification’; what doctrine was essential or non-essential; faith and works; and the nature of the real presence at the Eucharist. This is the period when Lutheranism developed, something which Luther himself predicted and condemned. The Schmalkald Articles had been drawn up in 1537 as a statement of faith. The Protestant princes had formed the Schmalkald League as a kind of defensive alliance against the Emperor. The tragic Schmalkald War broke out in 1547 in which the Emperor defeated the Protestant forces and imprisoned their leaders. But the Protestant Maurice of Saxony fought back successfully and by the Treaty of Passau (1552), Protestantism was legally recognised. This settlement was confirmed by the Interim of 1555. It was during this period that some of the Lutheran theologians drove large numbers of their own people over to the Calvinists through their dogmatism.

The Battle of Kappel, in which Zwingli was killed, had brought the Reformation in Switzerland to an abrupt halt, but in 1536 John Calvin (1509-64) was unwillingly pressed into reviving the cause in French-speaking Switzerland. Calvin was an exiled Frenchman, born in at Noyon in Picardy, whose theological writings, especially the Institutes of the Christian Religion and numerous commentaries on the Bible, did much to shape the Reformed churches and their confessions of faith. In contrast to Luther, Calvin was a quiet, sensitive man. Always a conscientious student, at Orléans, Bourges and the University of Paris, he soon took up the methods of humanism, which he later used ‘to combat humanism’. In Paris, the young Calvin had encountered the teachings of Luther and in 1533, he had experienced a sudden conversion:

God subdued and brought my heart to docility. It was more hardened against such matters than was to be expected in such a young man.

After that, he wrote little about his inner life, content to trace God’s hand controlling him. He next broke with Roman Catholicism, leaving France to live as an exile in Basle. It was there that he began to formulate his theology, and in 1536 published the first edition of The Institutes. It was a brief, clear defence of Reformation beliefs. Guillaume Farel, the Reformer of Geneva, persuaded Calvin to help consolidate the Reformation there. He had inherited from his father an immovable will, which stood him in good stead in turbulent Geneva. In 1537 all the townspeople were called upon to swear loyalty to a Protestant statement of belief. But the Genevans opposed Calvin strongly, and disputes in the town, together with a quarrel with the city of Berne, resulted in the expulsion of both Calvin and Farel.

Calvin went to Strasbourg, where he made contact with Martin Bucer, who influenced him greatly. Bucer (1491-1551) had been a Dominican friar but had left the order and married a former nun in 1522. He went to Strasbourg in 1523 and took over leadership of the reform, becoming one of the chief statesmen among the Reformers. He was present at most of the important conferences, or colloquies of the Reformers, and tried to mediate between Zwingli and Luther in an attempt to unite the German and Swiss Reformed churches. His discussions with Melanchthon led to peace in the debate over the sacraments at the Concord of Wittenberg. He also took part in the unsuccessful conferences with the Roman Catholics at Hagenau, Worms and Ratisbon.

In 1539, while in Strasbourg, Calvin published his commentary on the Book of Romans. Many other commentaries followed, in addition to a new, enlarged version of the Institutes. The French Reformer led the congregation of French Protestant refugees in Strasbourg, an experience which matured him for his task on returning to Geneva. He was invited back there in September 1541, and the town council accepted his revision of the of the city laws, but many more bitter disputes followed. Calvin tried to bring every citizen under the moral discipline of the church. Many naturally resented such restrictions, especially when imposed by a foreigner. He then set about attaining of establishing a mature church by preaching daily to the people. He also devoted much energy to settling differences within Protestantism. The Consensus Tigurinus, on the Lord’s Supper (1549), resulted in the German-speaking and French-speaking churches of Switzerland moving closer together. Michael Servetus, a notorious critic of Calvin, and of the doctrine of the Trinity, was arrested and burnt in Geneva.

John Calvin, caricatured by one of his students, during an idle moment in a lecture.

Calvin was, in a way, trying to build a more visible ‘City of God’ in Europe, with Geneva as its base and model. In his later years, Calvin’s authority in Geneva was less disputed. He founded the Geneva Academy, to which students of theology came from all parts of western and central Europe, particularly France. Calvin systemised the Reformed tradition in Protestantism, taking up and reapplying the ideas of the first generation of Reformers. He developed the Presbyterian form of church government, in which all ministers served at the same level, and the congregation was represented by lay elders. His work was characterised by intellectual discipline and practical application. His Institutes have been a classic statement of Reformation theology for centuries, as is evident from the following extracts:

Wherever we find the Word of God surely preached and heard, and the sacraments administered according to the Institution of Christ, there, it is not to be doubted, is a church of God.

We declare that by God’s providence, not only heaven and earth and inanimate creatures, but also the counsels and wills of men are governed so as to move precisely to that end destined by him.

Lutheranism strongly influenced Calvin’s doctrine. Like Luther, Calvin was also a careful interpreter of the Bible. He intended that his theology should interpret Scripture faithfully, rather than developing his own ideas. For him, all knowledge of God and man is to be found only in the Word of God. Man can only know God if he chooses to make himself known. Pardon and salvation are possible only through the free working of the grace of God. Calvin claimed that even before the creation, God chose some of his creatures for salvation and others for destruction. He is often known best for this severe doctrine of election, particularly that some people are predestined to eternal damnation. But Calvin also set out the way of repentance, faith and sanctification for believers. In his doctrine, the church was supreme and should not be restricted in any way by the state. He gave greater importance than Luther to the external organisation of the church. He regarded only baptism and communion as sacraments. Baptism was the individual’s initiation into the new community of Christ. He rejected Zwingli’s view that the communion elements were purely symbolic, but also warned against a magical belief in the real presence of Christ in the sacrament.

The Calvinists went further than the Lutherans in their opposition to traditions which had been handed down. They rejected a good deal of church music, art, architecture and many more superficial matters such as the use of the ring in marriage, and the signs of devotional practice. But all the Reformers rejected the authority of the pope, the merit of good works, indulgences, the mediation of the Virgin Mary and the saints, and all the sacraments which had not been instituted by Christ. They rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation (the teaching that the bread and wine of the communion became the body and blood of Christ when the priest consecrated them), the view of the mass as a sacrifice, purgatory and prayers for the dead, private confession of sin to a priest, celibacy of the clergy, and the use of Latin in the services.They also rejected all the paraphernalia that expressed these ideas, such as holy water, shrines, chantries, images, rosaries, paternoster stones and candles.

Meanwhile, in 1549 Bucer was forced to leave Strasbourg for Cambridge, and while in England, he advised Cranmer on The Book of Common Prayer. He had a great impact on the establishment of the Church of England, pointing it in the direction of Puritanism. Although he died in 1551, his body was exhumed and burned during the Catholic reaction under Queen Mary. Bucer wrote a large number of commentaries on the Bible and worked strenuously for reconciliation between various religious parties. In France, the pattern of reform was very different. Whereas in Germany and Switzerland there was solid support for the Reformation from the people, in France people, court and church provided less support. As a result, the first Protestants suffered death or exile. But once the Reformed faith had been established in French-speaking Switzerland and in Strasbourg, Calvinists formed a congregation in Paris in 1555. Four years later, over seventy churches were represented at a national synod in the capital.

Henry VIII may have destroyed the power of the papacy and ended monasticism in England, but he remained firmly Catholic in doctrine. England was no safe place for William Tyndale to translate the Bible into English, as Henry and the bishops were more concerned to prevent the spread of Lutheran ideas than to promote the study of Scripture. Tyndale narrowly escaped arrest in Cologne but managed to have the New Testament published in Worms in 1525. He was unable to complete the Old Testament because he was betrayed and arrested near Brussels in 1535. In October 1536 he was strangled and burnt at the stake. His last words were reported as, Lord, open the king of England’s eyes. In the meantime, Miles Coverdale completed the translation, which became the basis for later official translations.

The title page of the first Bible to be printed in English: Miles Coverdale’s translation (1535). Coverdale had helped Tyndale to revise his translation of the Pentateuch.

Though the king’s eyes were not immediately opened, a powerful religious movement towards reform among his people was going on at the same time. Despite the publication of the Great Bible in 1538, it was only under Edward VI (1547-53) that the Reformation was positively and effectively established in England. The leading figure was the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, supported by the scholar, Nicholas Ridley and the preacher, Hugh Latimer. Cranmer (1489-1556) was largely responsible for the shaping the Protestant Church of England. Born in Nottinghamshire, he was educated at Cambridge until he was suddenly summoned to Canterbury as Archbishop in 1532, as a result of Henry VIII’s divorce crisis. There he remained until he was deposed by Mary and burnt as a heretic at Oxford in 1556. He was a godly man, Lutheran in his theology, well read in the Church Fathers, a gifted liturgist with an excellent command of English. He was sensitive, cautious and slow to decide in a period of turbulence and treachery. He preferred reformation by gentle persuasion rather than by force, and, unlike Luther, also sought reconciliation with Roman Catholicism. Like Luther, however, he believed firmly in the role of the ‘godly prince’ who had a God-given task to uphold a just society and give free scope to the gospel.

Archbishop Cranmer (pictured above) was responsible for the Great Bible (1538) and its prefaces; the Litany (1545) and the two Prayer Books (1549, 1552). The driving force of Cranmer’s life was to restore to the Catholic Church of the West the faith it had lost long ago. When the Church of Rome refused to reform, Cranmer took it upon himself to reform his own province of Canterbury. He then sought an ecumenical council with the Lutherans and Calvinists, but Melanchthon was too timid. His second great concern was to restore a living theology based on the experience of the person and work of Christ. Thirdly, he developed the doctrine of the Holy Spirit which lay behind his high view of scripture and tradition, and the meaning of union with Christ. He was brainwashed into recanting, but at his final trial in 1556 he put up a magnificent defence and died bravely at the stake, thrusting the hand that had signed the recantations into the fire first. The Martyrs’ Memorial at Oxford commemorates his death, together with those of Ridley and Latimer whose deaths he had witnessed from prison a year earlier.

Several European Reformers also contributed to the Anglican Reformation, notably Martin , exiled from Strasbourg. These men, Calvinists rather than Lutherans, Bucerbecame professors at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Under the Counter-Reforming Catholic Queen Mary (1553-58), with Cardinal Pole as Archbishop of Canterbury, about two hundred bishops, scholars, ministers and preachers were burnt at the stake. Many Protestant reformers fled to the continent and became even more Calvinist in their convictions, influencing the direction of the English Reformation when they returned at the beginning of Elizabeth I’s reign. The young Queen gradually replaced the Catholic church leaders with Protestants, restored the church Articles and Cranmer’s Prayer Book. She took the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Her Anglican church kept episcopal government and a liturgy which offended many of the strict Protestants, particularly those who were returning religious refugees who had been further radicalised in Calvinist Switzerland or France.

Scotland was first awakened to Lutheranism by Patrick Hamilton, a student of Luther, who had been burned for his faith in 1528. George Wishart and John Knox (1505-72) continued Hamilton’s work, but Knox was taken prisoner by the French in 1547 and forced to serve as a galley-slave. When freed, he studied under Calvin at Geneva and did not return to Scotland until 1559, when he fearlessly launched the Reformation. He attacked the papacy, the mass and Catholic idolatry. The Catholic Mary Queen of Scots opposed Knox, but was beaten in battle. Knox then consolidated the Scots reformation by drawing up a Confession of Faith (1560), a Book of Discipline (1561) and the Book of Common Order (1564). While the Scottish Reformation was achieved independently from England, it was a great tragedy that it was imposed on Ireland, albeit through an Act of Uniformity passed by the Irish Parliament in 1560 which set up Anglicanism as the national religion. In this way, Protestantism became inseparably linked with English rule of a country which remained predominantly Catholic.

Western Europe during the Wars of Religion, to 1572.

The Empire of Charles V in 1551 (inset: The Swiss Confederation)

In Hungary, students of Luther and Melanchthon at Wittenberg took the message of the Reformation back to their homeland in about 1524, though there were Lollard and Hussite connections, going back to 1466, which I’ve written about in previous posts. As in Bohemia, Calvinism took hold later, but the two churches grew up in parallel. The first Lutheran synod was in 1545, followed by the first Calvinist synod in 1557. In the second half of the sixteenth century, a definite interest in Protestant England was already noticeable in Hungary. In contemporary Hungarian literature, there is a long poem describing the martyr’s death of Thomas Cranmer (Sztáray, 1582). A few years before this poem was written, in 1571, Matthew Skaritza, the first Hungarian Protestant theologian made his appearance in England, on a pilgrimage to ‘its renowned cities’ induced by the common religious interest.

Protestant ministers were recruited from godly and learned men. The Church of England and large parts of the Lutheran church, particularly in Sweden, tried to keep the outward structure and ministry of their national, territorial churches. Two brothers, Olav and Lars Petri, both disciples of Luther, inaugurated the Reformation in Sweden. The courageous King Gustavus Vasa, who delivered Sweden from the Danes in 1523, greatly favoured Protestantism. The whole country became Lutheran, with bishops of the old church incorporated into the new, and in 1527 the Reformation was established by Swedish law. This national, state church was attacked by both conservative Catholics and radical Protestants.

The Danish Church, too, went over completely to Protestantism. Some Danes, including Hans Tausen and Jörgen Sadolin, studied under Luther at Wittenberg. King Frederick I pressed strongly for church reform, particularly by appointing reforming bishops and preachers. As a result, there was an alarming defection of Catholics and in some churches no preaching at all, and a service only three times a year. After this, King Christian III stripped the bishops of their lands and property at the Diet of Copenhagen (1536) and transferred the church’s wealth to the state. Christian III then turned for help to Luther, who sent Bugenhagen, the only Wittenberger theologian who could speak the dialects of Denmark. Bugenhagen crowned the king and appointed seven superintendents. This severed the old line of bishops and established a new line of presbyters. At the synods which followed church ordinances were published, and the Reformation recognised in Danish law. The decayed University of Copenhagen was enlarged and revitalised. A new liturgy was drawn up, a Danish Bible was completed, and a modified version of the Augsburg Confession was eventually adopted.

Heddal Stave church, Norway.

This form of construction is characteristic of this part of Scandinavia

The Reformation spread from Denmark to Norway in 1536. The pattern was similar to that of Denmark. Most of the bishops fled and, as the older clergy died, they were replaced with Reformed ministers. A war between Denmark and Norway worsened social and political conditions. When the Danish Lutherans went to instruct the Norwegians, they found that many of the Norwegians spoke the incomprehensible old Norse, and communications broke down. In Iceland, an attempt to impose the Danish ecclesiastical system caused a revolt. This was eventually quelled and the Reformation was imposed, but with a New Testament published in 1540.

Calvinists held an exalted and biblical view of the church as the chosen people of God, separated from the state and wider society. They, therefore, broke away from the traditional church structures as well as the Roman ministry. The spread of Calvinism through key sections of the French nobility, and through the merchant classes in towns such as La Rochelle alarmed Catherine de Medici, the French Regent, resulting eventually in the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572. Philip II faced a similarly strong Calvinist challenge in the United Provinces of the Netherlands. In 1565, an outbreak of anti-Catholic rioting could not be contained because all the available forces were deployed in the Mediterranean to defend southern Italy from the Turks and to lift the siege of Malta. The spread of Calvinism was a coral growth in ports and free cities, compared with the territorial growth of Lutheranism which was dependent on earthly principalities and powers.

In this, the free churches later followed them. These churches were mainly fresh expressions of Calvinism which started to grow at the beginning of the next century, but some did have links to, or were influenced by, the churches founded in the aftermath of the Radical Reformation. Only three groups of Anabaptists were able to survive beyond the mid-sixteenth century as ordered communities: the ‘brethren’ in Switzerland and southern Germany, the Hutterites in Moravia and the Mennonites in the Netherlands and northern Germany.

In the aftermath of the suppression of Münster, the dispirited Anabaptists of the Lower-Rhine area were given new heart by the ministry of Menno Simons (about 1496-1561). The former priest travelled widely, although always in great personal danger. He visited the scattered Anabaptist groups of northern Europe and inspired them with his night-time preaching. Menno was an unswerving, committed pacifist. As a result, his name in time came to stand for the movement’s repudiation of violence. Although Menno was not the founder of the movement, most of the descendants of the Anabaptists are still called ‘Mennonites’. The extent to which the early Baptists in England were influenced by the thinking of the Radical Reformation in Europe is still hotly disputed, but it is clear that there were links with the Dutch Mennonites in the very earliest days.

Reformers, Revolutionaries and Anti-Semites:

Luther had early believed that the Jews were a stiff-necked people who rejected Christ, but that contemporary Jews could not be blamed for the sins of their fathers and might readily be excused for their rejection of Christianity by reason of the corruption of the Medieval Papacy. He wrote, sympathetically:

If I were a Jew, I would suffer the rack ten times before I would go over to the pope.

The papists have so demeaned themselves that a good Christian would rather be a Jew than one of them, and a Jew would rather be a sow than a Christian.

What good can we do the Jews when we constrain them, malign them, and hate them as dogs? When we deny them work and force them to usury, how can that help? We should use towards the Jews not the pope’s but Christ’s law of love. If some are stiff-necked, what does that matter? We are not all good Christians.

Luther was sanguine that his own reforms, by eliminating the abuses of the papacy, would accomplish the conversion of the Jews. But the coverts were few and unstable. When he endeavoured to proselytise some rabbis, they undertook in return to make a Jew out of him. The rumour that a Jew had been authorised by the papists to murder him was not received with complete incredulity. In his latter days, when he was more easily irritated, news came that in Moravia, Christians were being induced to become Judaic in beliefs and practice. That was what induced him to come out with his rather vulgar blast in which he recommended that all Jews be deported to Palestine. Failing that, he wrote, they should be forbidden to practice usury, should be compelled to earn their living on the land, their synagogues should be burned, and their books, including The Torah, should be taken away from them.

The content of this tract was certainly far more intolerant than his earlier comments, yet we need to be clear about what he was recommending and why. His position was entirely religious and not racially motivated. The supreme sin for him was the persistent rejection of God’s revelation of himself in Jesus Christ. The centuries of persecution suffered by the Jews were in themselves a mark of divine displeasure. The territorial principle should, therefore, be applied to the Jews. They should be compelled to leave and go to a land of their own. This was a programme of enforced Zionism. But, if this were not feasible, Luther would recommend that the Jews be compelled to live from the soil. He was, perhaps unwittingly, proposing a return to the situation which had existed in the early Middle Ages, when the Jews had worked in agriculture. Forced off the land, they had gone into commerce and, having been expelled from commerce, into money-lending. Luther wished to reverse this process and to accord the Jews a more secure, though just as segregated position than the one they had in his day, following centuries of persecutions and expulsions.

His advocacy of burning synagogues and the confiscation of holy books was, however, a revival of the worst features of the programme of a fanatical Jewish convert to Christianity, Pfefferkorn by name, who had sought to have all Hebrew books in Germany and the Holy Roman Empire destroyed. In this conflict of the early years of the Reformation, Luther had supported the Humanists, including Reuchlin, the great German Hebraist and Melanchthon’s great-uncle. Of course, during the Reformation throughout Europe, there was little mention of the Jews except in those German territories, like Luther’s Saxony, Frankfurt and Worms, where they were tolerated and had not been expelled as they had been from the whole of England, France and Spain. Ironically, Luther himself was very Hebraic in his thinking, appealing to the wrath of Jehovah against any who would impugn his picture of a vengeful, Old Testament God. On the other hand, both Luther and Erasmus were antagonistic towards the way in which the Church of their day had relapsed into the kind of Judaic legalism castigated by the Apostle Paul. Christianity, said Erasmus, was not about abstaining from butter and cheese during Lent, but about loving one’s neighbour. This may help to explain Luther’s reaction to the Moravian ‘heresy’ in terms which, nevertheless, only be described as anti-Semitic, even by the standards of his time.

The story told in Cohn’s great book Pursuit of the Millennium, originally written six decades ago, is a story which began more than five centuries ago and ended four and a half centuries ago. However, it is a book and a story not without relevance to our own times. In another work, Warrant for Genocide: the myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, published in 1967, Cohn shows how closely the Nazi fantasy of a world-wide Jewish conspiracy of destruction is related to the fantasies that inspired millenarian revolutionaries from the Master of Hungary to Thomas Müntzer. The narrative is one of how mass disorientation and insecurity have fostered the demonisation of the misbelievers, especially the Jews, in this as much as in previous centuries.

We can also reflect on the damage wrought in the twentieth century by left-wing revolutions and revolutionary movements, which are just as capable of demonising religious and ethnic groups, including Jews, through their love of conspiracy theories and narratives. What is most curious about the popular Müntzer ‘biopic’, for example, is the resurrection and apotheosis which it has undergone during the past hundred and fifty years. From Engels through to the post-Marxist historians of this century, whether Russian, German or English-speaking, Müntzer has been conflated into a giant symbol, a prodigious hero in the history of ‘class warfare’. This is a naive view and one which non-Marxist historians have been able to contradict easily by pointing to the essentially mystical nature of Müntzer’s preoccupations which usually blinded him to the material sufferings of the poor artisans and peasants. He was essentially a propheta obsessed by eschatological fantasies which he attempted to turn into reality by exploiting social discontent and dislocation through revolutionary violence against the misbelievers. Perhaps it was this obsessive tendency which led Marxist theorists to claim him as one of their own.

Just like the medieval artisans integrated in their guilds, industrial workers in technologically advanced societies have shown themselves very eager to improve their own conditions; their aim has been the eminently practical one of achieving a larger share of economic security, prosperity and social privilege through winning political power. Emotionally charged fantasies of a final, apocalyptic struggle leading to an egalitarian Millennium have been far less attractive to them. Those who are fascinated by such ideas are, on the one hand, the peoples of overpopulated and desperately poor societies, dislocated and disoriented, and, on the other hand, certain politically marginalised echelons in advanced societies, typically young or unemployed workers led by a small minority of intellectuals.

Working people in economically advanced parts of the world, especially in modern Europe, have been able to improve their lot out of all recognition, through the agency of trade unions, co-operatives and parliamentary parties. Nevertheless, during the century since 1917 there has been a constant repetition, on an ever-increasing scale, of the socio-psychological process which once connected the Táborite priests or Thomas Müntzer with the most disoriented and desperate among the poor, in fantasies of a final, exterminating struggle against ‘the great ones’; and of a perfect, egalitarian world from which self-seeking would be forever banished. We are currently engaged in yet another cycle in this process, with a number of fresh ‘messiahs’ ready to assume the mantles of previous generations of charismatic revolutionaries, being elevated to the status of personality cults. Of course, the old religious idiom has been replaced by a secular one, and this tends to obscure what would otherwise be obvious. For it is a simple truth that stripped of its original supernatural mythology, revolutionary millenarianism is still with us.

Sources:

John H. Y. Briggs (1977), The History of Christianity. Berkhamsted: Lion Publishing.

Sándor Fest (2000), Skóciai Szent Margittól, A Walesi Bárdokig: Magyar-Angol történeti és irodalmi kapcsalatok.

Norman Cohn (1970), The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages. St Albans: Granada Publishing.

Roland H. Bainton (1950), Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther. Nashville, USA: Abingdon Press.

András Bereznay (1994, 2001), The Times Atlas of European History. London: HarperCollins.

Posted February 4, 2018 by AngloMagyarMedia in Anabaptism, Anglican Reformation, anti-Semitism, Apocalypse, Austria-Hungary, Britain, British history, Christian Faith, Church, Commemoration, Early Modern English, Egalitarianism, Empire, English Language, Europe, France, Germany, Henry VIII, History, Humanism, Hungarian History, Hungary, Ireland, Irish history & folklore, Jews, Linguistics, Lutheranism, Martin Luther, Medieval, Mediterranean, Messiah, Middle English, Migration, Millenarianism, Monarchy, Music, Mysticism, Mythology, Narrative, nationalism, New Testament, Old Testament, Papacy, Reformation, Remembrance, Shakespeare, Switzerland, theology, Tudor England, Uncategorized, Warfare, Zionism

Tagged with Anabaptists, Apostle Paul, Augsburg, Basle, Battle of Kappel, Bohemia, Book of Common Prayer, Book of Romans, Brussels, Bucer, Bugenhagen, Calvinism, Cambridge, Cardinal Pole, Catherine de Medici, Charles V, Christian III, Christianity, Cologne, communion, conspiracy theories, Copenhagen, Counter-Reformation, Denmark, Edward VI, Elizabeth I, England, Erasmus, Faith, Farel, France, Frankfurt, Frederick I of Denmark, Geneva, George Herbert, George Wishart, Great Bible, Heddal Stave church, History, Holy Roman Empire, Hungary, Hutterites, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Jörgen Sadolin, Jean Calvin, John Knox, justification, Kappel, King Gustavus Vasa, La Rochelle, Latimer, litugy, Lower-Rhine, Malta, Mansfeld, Martin Bucer, Mary Queen of Scots, Mary Tudor, Master of Hungary, Matthew Skaritza, Münster, Müntzer, Melanchthon, Menno Simons, Mennonites, Millennium, Monasticism, Moravia, Nazis, Norway, Old Testament, Oxford, Papacy, Paris, Patrick Hamilton, Petri, Pfefferkorn, Philip II of Spain, politics, pope, Presbyterianism, Prince Maurice, recantation, Refugees, religion, Reuchlin, Ridley, Roman Curia, sanctification, Saxony, Scandinavia, Schmalkald, Scotland, society, Spain, Speyer, St Bartholomew's Massacre, Strasbourg, Sweden, Swiss Confederation, Tausen, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Thomas Cranmer, Torah, transubstantiation, Treaty of Passau, Turks, Tyndale, United Provinces of the Netherlands, Westminster Divines, Wittenberg, Worms, Zwingli

Part Six – Zwingli, Luther and the Anabaptists, 1525-35:

The Lutheran Reformation had been accompanied by certain phenomena which, though they appalled Luther and his associates, were so natural as to appear in retrospect. As against the authority of the Church of Rome, the Reformers appealed to the text of the Bible. But once men were able to read the Bible for themselves, in their own language, they began to interpret it for themselves; their own interpretations did not always accord with those of the Reformers. Wherever Luther’s influence extended the priest lost much of his traditional prestige as a mediator between the layman and God. Once the layman could stand face to face with God and rely for guidance on his individual conscience, it was inevitable that some laymen should claim divine promptings which ran as much counter to the new as to the old orthodoxy.

For many centuries, the Church of Rome, whatever its failings, had been fulfilling a very important normative function in European society. Luther’s onslaught, precisely because it was so effective, seriously disturbed that function. As a result, it produced, along with a sense of liberation, a sense of disorientation which was just as widespread. Moreover, the Lutheran Reformation could not itself master all the anxieties which it had released in the population. Partly because of the content of his doctrine of salvation, partly because of his alliance with the established secular powers, Luther failed to hold the allegiance of great multitudes of the common people. Amongst the perturbed, disoriented masses there grew up, in opposition to both Lutheranism and Roman Catholicism, the movement to which its opponents gave the name of Anabaptism – in many ways a successor to the medieval sects, but a far larger movement which spread over most of west and central Europe.

By 1525, Zurich was the seat of a new variety of the Reformation which was to be set over against that of Wittenberg and characterised as the Reformed. The leader was Huldreich Zwingli who had received a Humanist training as a Catholic priest, and on the appearance of Erasmus’ New Testament he committed the epistles to memory in Greek and affirmed in consequence that Luther had been able to teach him nothing about the understanding of Paul. But what Zwingli selected for emphasis in Paul was the text: The letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life, which he coupled with a Johannine verse; The flesh profiteth nothing. By ‘flesh’ Zwingli meant the body in the Platonic sense, whereas Luther took it to mean, in the Hebraic sense, the ‘evil heart’. Zwingli, therefore, made a characteristic deduction from his disparagement of the body that art and music were inappropriate as the ‘handmaids of religion’ though he himself was an accomplished musician.

His next logical step was to deny the ‘real presence’ of Christ in the Eucharistic, reducing the sacrament to a symbolic commemoration of the crucifixion, just as the Passover meal had been a memorial to the escape of the Hebrews from Egypt. Jesus’ words, this is my body… this is the new testament in my blood… could just as easily be translated as this signifies… Luther sensed at once the affinity between these views and those of Carlstadt whom he had effectively banished from Wittenberg for his support of iconoclasm. Luther also recognised a similarity with the views of Müntzer in Zwingli, in particular his willingness to turn to politics and even to countenance the use of the sword in the name of the faith. Zwingli was a Swiss patriot, and in translating the twenty-third psalm he rendered the second verse as… He maketh me to lie down in an Alpine meadow. But there he could find no still waters, but only fast-flowing streams. The evangelical issue threatened to disrupt his beloved confederation, for the Catholics turned to the traditional enemy, the House of Habsburg. Ferdinand of Austria was instrumental in the calling of the assembly of Baden to discuss Zwingli’s theory of the sacrament.

This was the Swiss reformer’s Diet of Worms and he became convinced that the gospel could only be saved in Switzerland and the Confederation if the Catholic League with Austria were countered by an evangelical league with the German Lutherans, ready if need be to use the sword. The very notion of a military alliance for the defence of the gospel reminded Luther of Thomas Müntzer. Not only that, but the ‘home’ sphere of Luther’s activity was constantly being encroached upon. The Catholics, both clerical and lay, were determined to launch their counter-reformation. The Swiss, the south German Protestant cities and the Anabaptists had all developed divergent forms of the reformed faith. Even Wittenberg had experienced its radical moments and might not be free from fresh infiltrations from the sectaries. But Luther was more determined than ever to carve out enough space in between for his territorial church, working with the ‘godly princes’. He made a clear-cut division between the concerns and responsibilities of the church and state.

The radicals, sometimes called ‘enthusiasts’, wanted to carry out a complete spiritual transformation of the church, and expected Christians to live by the standards and teachings of Scripture. Their reform programme was, however, more far-reaching than most people were prepared to accept, especially in the rural areas where the activism of Müntzer and the peasants had led to such indescribable misery following the massacres, mass executions, destruction of farms, agricultural implements and livestock. However, Anabaptism was not a homogeneous movement and was never centrally organised. There existed some forty independent sects of Anabaptists, each grouped around a leader who claimed to be a divinely inspired prophet or apostle, following in the apostolic succession. These sects, often clandestine, constantly threatened with extermination, scattered throughout the German-speaking lands, developed along the separate lines which the various leaders set. Nevertheless, certain tendencies were common to the movement as a whole.

In some parts of the Anabaptist movement which spread far and wide during the years following the Peasants’ War, Müntzer’s memory was venerated, even though he had never called himself an Anabaptist. Other parts of rejected his legacy. Again, this was because they did not, at first, emerge as a single, coherent organisation, but as a loose grouping of movements. All of these rejected infant baptism and practised the baptism of adults upon confession of faith. They themselves never accepted the label ‘Anabaptist’ (meaning ‘rebaptizer’), a term of reproach coined by their opponents, since they objected to the implication that the ceremonial sprinkling which they had received as infants had in fact been a valid baptism. They denied that their baptism of believing adults was arrogant and superfluous. They also soon discovered that the term gave the authorities a legal pretext for persecuting and executing them, based on Roman laws harking back to the fifth century.

For the ‘Anabaptists’ themselves, however, baptism was not the fundamental issue involved in their sectarianism. More basic was their growing conviction about the role the civil government should play in the reformation of the church. Late in 1523 intense debate broke out in Zürich. At that time it became clear that the city council was unwilling to bring about the religious changes that the theologians believed were called for by Scripture. Zwingli believed that the reformers should wait and attempt to persuade the authorities by preaching. The ‘Anabaptists’ believed that the community of Christians, the corpus Christianum, should follow the leading of the Holy Spirit and initiate Scripture-based reforms regardless of the views of the council. Despite continuing efforts to discuss the matters in dispute between the reformists and the radicals – the mass, baptism and tithes – the gap between the two parties widened. Finally, on 21 January 1525, came a complete rupture. On that day the city council forbade the radicals to assemble or disseminate their views. That evening, in the neighbouring village of Zollikon, praying that God would grant them to do his divine will and that he would show them mercy, the radicals met, baptized each other, and so became the first free church of modern times.

Their point of departure from the ‘mainstream’ reformers was another aspect of Erasmus’ programme and a point which was also important to Zwingli himself. This was the restoration of primitive Christianity, which they took to mean the adoption of the Sermon on the Mount as a literal code for all Christians, who should renounce oaths, the use of the sword whether in war or civil government, private possessions, bodily adornment, revelling and drunkenness. Pacifism, religious communitarianism, simplicity and temperance marked their communities. The church should consist only of the twice-born, committed to the covenant of discipline. Here again was the concept of ‘the Elect’, discernible by the two tests of spiritual experience and moral achievement. The Church should not rest on the baptism administered in infancy, but on regeneration, symbolised by baptism during or after ‘the years of discretion’. Every member should be a priest, a minister, and a missionary prepared to embark on evangelistic tours. Such a Church, though seeking to convert the world and not to exclude anyone from hearing the gospel message, could never embrace the unconverted community, however. Since the State comprised all the inhabitants, the Church would need to separate itself from its control and free itself from all magisterial constraint.

Zwingli was aghast to see the medieval unity of Church and State shattered and in panic invoked the arm of the state. In 1525 the Anabaptists in Zürich were subjected to the death penalty. Luther was not yet ready for such savage expedients, but he too was appalled by what to him appeared to be a reversion to the monastic attempt to win salvation by a higher righteousness. The leaving of families for missionary expeditions was in his eyes a sheer desertion of domestic responsibilities, and the repudiation of the sword prompted him to a new vindication of the divine calling alike of the magistrate and the soldier. But he was very much conflicted over the whole matter of the executions. In 1527, he wrote:

It is not right, and I am deeply troubled that the poor people are so pitifully put to death, burned, and cruelly slain. Let everyone believe what he likes. If he is wrong, he will have punishment enough in hell fire. Unless there is sedition, one should oppose them with Scripture and God’s Word. With fire you won’t get anywhere.

This did not mean, however, that Luther considered one faith as good as another. Most emphatically he believed that the wrong faith would entail hell-fire; although the true faith could not be created by coercion, it could be relieved of impediments. The magistrate should certainly not suffer the faith to be blasphemed. Unlike the ‘mainstream’ reformers, the Anabaptists were not committed to the notion that ‘Christendom’ was Christian. From the beginning, they saw themselves as missionaries to people of lukewarm piety, only partly obedient to the gospel. The Anabaptists systematically divided Europe into sectors for evangelistic outreach and sent missionaries out into them in twos and threes. Many people were bewildered by their message; others pulled back when the cost of Anabaptist discipleship became clear. But others heard them gladly.

In general, the Anabaptists attached relatively little importance either to theological speculations or formal religious observances. In place of such practices as daily church-going, they set a meticulous, literal observance of the precepts that they thought they found in the New Testament. In place of theology, they cultivated the Bible, which they were apt to interpret in the light of the direct inspirations which they believed they received from God. Their values were primarily ethical; for them, religion was above all a matter of active brotherly love. Their communities were modelled on what they supposed to have been the practice of the early Church and were intended to realise the ethical ideal propounded by Christ.

The diverse backgrounds of their leaders and the absence of any ecclesiastical authority to control them were enough to ensure diversity of belief and practice. They did, however, attempt to agree upon a common basis. In 1527 at Schleitheim, on today’s Swiss-German border near Schaffhausen, the Anabaptists called the first ‘synod’ of the Protestant Reformation. The leading figure at this meeting was the former Benedictine prior, Michael Sattler, who, four months later, was burned at the stake in nearby Rottenberg-am-Neckar. The ‘Brotherly Union’ adopted at Schleitheim was to be a highly significant document. During the next decade, most Anabaptists in all parts of Europe came to agree with the beliefs which it laid down.

It was in their social Attitudes that the Anabaptist were most distinct. These sectarians tended to be uneasy about private property and to accept community of goods as an ideal. If in most of the groups little attempt was made to introduce common ownership, Anabaptists certainly did take seriously the obligations of charitable dealing and generous mutual aid. On the other hand Anabaptist communities, facing continual persecution, often showed a marked exclusiveness. Within each group, there was great solidarity, but the attitude towards society at large tended to be one of rejection.

In particular, Anabaptists regarded the state with suspicion, as an institution which, though no doubt necessary for the unrighteous, was unnecessary for true Christians. Though they were willing to comply with many of the state’s demands, they refused to let it invade the realm of faith and conscience; in general, they preferred to minimise their dealings with it. Most Anabaptists refused to hold an official position in the state, or to invoke the authority of the state against a fellow Anabaptist, or to take up arms on behalf of the state. The attitude towards private persons who were not Anabaptists was equally aloof; Anabaptists commonly avoided all social intercourse outside their own community. Many regarded themselves as the only Elect and their communities as being alone under the immediate guidance of God; small islands of righteousness in an ocean of iniquity. But the history of the movement was punctuated by schisms over this obsession with exclusive election, which some were more obsessed with than others.

The movement spread from Switzerland into Germany. Mysticism, late-medieval asceticism and the disillusionment which followed the Peasants’ War of 1525 had prepared the way for them. Most Anabaptists were peaceful folk who in practice were quite willing, except in matters of conscience and belief, to respect the authority of the state. Certainly, the majority had no thought of social revolution. But the rank-and-file were recruited almost entirely from the ranks of peasants and artisans; after the Peasants’ War, the authorities were nervous of these classes. Even the most peaceful Anabaptists were therefore ferociously persecuted and many thousands of them were killed.

By 1527, the German Reformers and their princely allies had determined to use all necessary means to root out Anabaptism. They were joined in this determination by the Catholic authorities. To Protestants and Catholics alike, the Anabaptists seemed not only to be dangerous heretics; they also seemed to threaten the religious and social stability of Christian Europe. Their growth constituted a very real problem to the territorial church since, despite the decree of death visited upon them at the Diet of Speyer in 1529 with the concurrence of the Evangelicals, the fearlessness and saintliness of the martyrs had enlisted converts to the point of threatening to depopulate the established churches. Philip of Hesse observed more improvement of life among the sectaries than among the Lutherans, and a Lutheran pastor who wrote against the Anabaptists testified that they went in among the poor, appeared very lowly, prayed much, read from the Gospel, talked especially about the outward life and good works, about helping the neighbour, giving and lending, holding goods in common, exercising authority over none, and living with all as brothers and sisters. Such were the people executed by Elector John in Saxony. In the carnage of the next quarter-century, thousands of Anabaptists were put to death; thousands more saved their skins by recanting.

But the blood of the martyrs proved again to be the seed of the church. This persecution, in the end, created the very danger it was intended to forestall. It was not only that the Anabaptists were confirmed in their hostility to the state and the established order, but that they also interpreted their sufferings in apocalyptic terms, as the last great onslaught of Satan and Antichrist against the Saints, as those ‘messianic woes’ which were to usher in the Millennium. Many Anabaptists became obsessed with imaginings of a day of reckoning when they themselves would arise to overthrow the mighty and, under a Christ who had returned at last, establish a Millennium on earth. The situation within Anabaptism now resembled that which had existed within the heretical movements of previous centuries, like the Waldesians. The bulk of the Anabaptists continued in their tradition of peaceful and austere dissent. But alongside it there was growing up in Anabaptism of another kind, in which the equally ancient tradition of militant millenarianism was finding a new expression.