‘Out of Darkness Cometh Light’: Wolves celebrate 125 Years at Molineux.

Mercian Origins

A century and a quarter ago, on Monday 2nd September 1889 at 5.30 p.m. a crowd of around 3,900 spectators gathered at ‘Molineux’ (pronounced ‘MOL-i-new’), the new home ground of Wolverhampton Wanderers to watch a friendly game against their Midland rivals Aston Villa. The previous year, ‘Wolves’ had joined the Football League for the 1888/89 season, playing their first ever league fixture on their sloping pitch at Dudley Road on 8 September 1889, a 1-1 draw, also with the Villa.

The club had come into being in 1877 when St Luke’s school in Blakenhall formed a football team, which became Wolverhampton Wanderers a couple of years later when it merged with Blakenhall Wanderers cricket club. They soon became known popularly as ‘The Wolves’, since the town’s name comes from the Mercian royal Saxon name of Wulfrun or Wulfhere, derived from the totemic Wolf symbol, the townspeople are known as Wulfrinians, and the town’s nickname is ‘Wolftown’ (the suffixes ‘ham’ and ‘ton’ referred to a fortified farmstead, or manor in Saxon times).

The Molineux Family

In simple terms, Molineux takes its name from the family that owned and lived on the site in the eighteenth century. The ancestors of the Molineux family brought their name to England in the wave of migration after the Norman Conquest of 1066 and, like many Norman-French noble names, is a reference to the family’s place of residence prior to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, Moulineaux-Sur-Seine, near Rouen, in Normandy, which is the site of Castle Molineux. The Norman-English family settled on the manors they were given and developed into two branches, one in Lancashire, around Merseyside especially, and the other throughout Nottinghamshire. A third branch settled around Calais and settled in Staffordshire as merchants and makers of woollen cloth in the time of Isabella of France’s reign over England, during the first half of the fourteenth century, first as wife of Edward II and then as Regent to her son, Edward III, whose taxes on the wool trade brought Flemish weavers and wool-workers to settle and begin the domestic industry and trade in woollens in England. Wolverhampton then became an important wool town and, as the trade progressed, famous throughout Europe.

The dawning of the industrial era created a great deal of wealth for those who had the vision, craft and acumen to capitalise on the the technological innovation that followed the Quaker ironmaster, Abraham Darby’s successful introduction of coke smelting in 1709. In these early stages of the revolution in iron production in Shropshire and Staffordshire, which led to the area becoming known as ‘the Black Country’, John Molineux (b. 1675) was an ironmonger, supplying manufacturers with their raw materials, then selling their finished goods. He became an extremely successful and wealthy businessman. He began by selling Black Country hardware such as brass and iron in Dublin, then returned to Wolverhampton and set himself up as an ironmaster in Horseley Fields, where he had two houses with workshops at the back. John and his wife Mary had five sons and three daughters. Their fifth and youngest son, Benjamin, became an ironmonger like his father, and ran his uncle Daniel’s warehouse in Dublin, where he stored and sold all kinds of goods such as locks, hinges, tools, and saddler’s goods. He also sold Birmingham-made steel toys. At the time, the trade between Britain and the West Indies had increased greatly, and so Benjamin exported many of his goods to that region. He also imported Jamaica rum, and in 1775 opened a Jamaica rum warehouse in Wolverhampton, where he also became a banker. He invested in the local canals, and made many astute loans, becoming one of the most successful businessmen in the area. Another of their children, Thomas, also became wealthy and built himself a large house in Dudley Street, Wolverhampton. The house, which was built in 1751, had imposing entrance gates, and an ornamental garden that extended to Pipers Row. Thomas married Margaret Gisborne on the 5th August, 1732, at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. They had nine sons and three daughters, most of whom died in infancy.

The family residence in Tup Street, Wolverhampton, which became known as ‘Mr Molineuxe’s Close’, came into the possession of the family in 1744 after the death of the original owner, John Rotton, who owed Benjamin Molineux £700. The beneficiaries of his will (his wife, and his business partner Richard Wilkes), agreed to sell the property, and around eight acres of surrounding land, to the Molineux family to pay off the debt. Little is known about the original property, which was probably built around 1720.

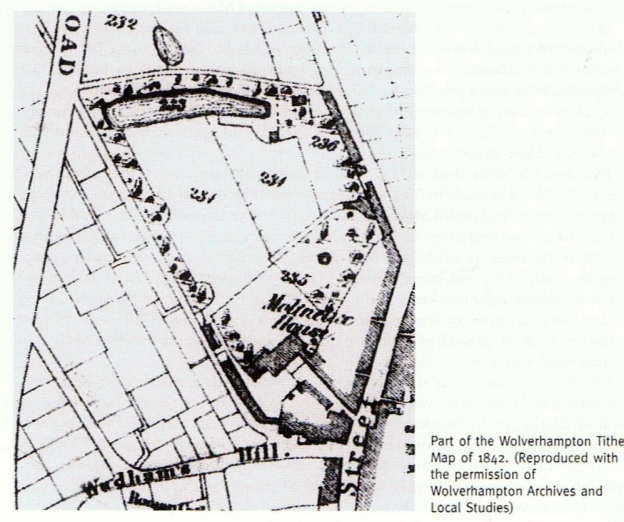

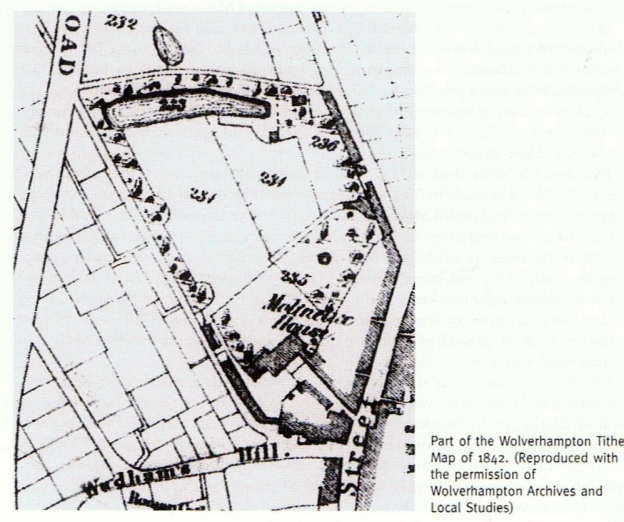

The family residence in Tup Street, Wolverhampton, which became known as ‘Mr Molineuxe’s Close’, came into the possession of the family in 1744 after the death of the original owner, John Rotton, who owed Benjamin Molineux £700. The beneficiaries of his will (his wife, and his business partner Richard Wilkes), agreed to sell the property, and around eight acres of surrounding land, to the Molineux family to pay off the debt. Little is known about the original property, which was probably built around 1720.  The Molineux family extended the house, and added a fine rear extension, which looked even better than the main façade. What is certain that by 1750 work had finished on the house, and the rear formal garden, because they appear on Isaac Taylor’s map (see opposite), which was drawn during that year. By the time the ‘Tithe Map’ was published, in 1842, it had become known as ‘Molineux House’. It stood proudly on a hill overlooking extensive gardens, with delightful views of the Clee Hills and the Wrekin, together with panoramic views of Chillington and the woods. one of the largest houses in the town.

The Molineux family extended the house, and added a fine rear extension, which looked even better than the main façade. What is certain that by 1750 work had finished on the house, and the rear formal garden, because they appear on Isaac Taylor’s map (see opposite), which was drawn during that year. By the time the ‘Tithe Map’ was published, in 1842, it had become known as ‘Molineux House’. It stood proudly on a hill overlooking extensive gardens, with delightful views of the Clee Hills and the Wrekin, together with panoramic views of Chillington and the woods. one of the largest houses in the town.

Benjamin Molineux died in 1772, by which time the family had already become accepted into the ranks of the local gentry. They continued to reside in Molineux House until 1856, the last family occupant being Charles Edward Molineux. On 6 April 1859, the house was advertised for sale by private treaty, being described as ‘a handsome and spacious mansion, with extensive out-offices, buildings, coach-houses, stabling, and beautiful grounds, plus gardens, pool, elegant conservatory and greenhouses, four and a half acres within the walls. A further three-and-a-half extending from the grounds of Molineux House and fronting the Waterloo Road could be purchased separately.

So it was that the estate was bought in 1860 by Mr O E McGregor, obviously another man with a vision. He retained the name ‘Molineux Grounds’, spending seven thousand pounds on returning the house to its former glory, and converting the rest of the estate into a pleasure park, which he then opened to the public for a small admission fee. The ‘Grounds’, the first park of its kind in Wolverhampton, boasted a number of different attractions, including a skating rink, a boating lake with fountain, croquet lawns, flower-beds, walkways and lawns, plus amenities for football and cricket, and soon became established as a popular place of recreation, with many fetes and galas being held there, including the 1869 South Staffordshire Industrial and Fine Arts Exhibition.

So it was that the estate was bought in 1860 by Mr O E McGregor, obviously another man with a vision. He retained the name ‘Molineux Grounds’, spending seven thousand pounds on returning the house to its former glory, and converting the rest of the estate into a pleasure park, which he then opened to the public for a small admission fee. The ‘Grounds’, the first park of its kind in Wolverhampton, boasted a number of different attractions, including a skating rink, a boating lake with fountain, croquet lawns, flower-beds, walkways and lawns, plus amenities for football and cricket, and soon became established as a popular place of recreation, with many fetes and galas being held there, including the 1869 South Staffordshire Industrial and Fine Arts Exhibition.

The Wolves arrive at the Molineux Grounds, 1889

By 1872, the grounds had been further developed to include a number of other attractions, and the arena facilities were used to stage a number of sporting events including cycle racing, football and cricket matches. When, subsequently, Northampton Brewery acquired the entire site, they converted Molineux House into a hotel and, in 1889 rented the grounds to Wolverhampton Wanderers for a very low annual rent of fifty pounds.

By 1872, the grounds had been further developed to include a number of other attractions, and the arena facilities were used to stage a number of sporting events including cycle racing, football and cricket matches. When, subsequently, Northampton Brewery acquired the entire site, they converted Molineux House into a hotel and, in 1889 rented the grounds to Wolverhampton Wanderers for a very low annual rent of fifty pounds.

They calculated that they could make many times that from the thirsty thousands who would attend each match. By 1901, the building was purchased by W. Butler & Co., the Wolverhampton brewers. It still maintained it architectural attraction when I went to watch games with my father in the 1960s and 70s (see photo left), but closed in 1979 and the fine old building was allowed, tragically, to fall into dereliction.

The Wolves had first played a game on ‘The Molineux Grounds’, as they were then known, in 1886, losing 2-1 to their neighbours, Walsall Town in the final of the Walsall Cup. In 1888, the club reached its first FA Cup final, losing 1-0 to Preston North End. The new grounds matched the growing aspirations of the committee members who decided to accept the offer to move to the Molineux Leisure Grounds, and so the ‘legendary’ Molineux story began.

The Wolves had first played a game on ‘The Molineux Grounds’, as they were then known, in 1886, losing 2-1 to their neighbours, Walsall Town in the final of the Walsall Cup. In 1888, the club reached its first FA Cup final, losing 1-0 to Preston North End. The new grounds matched the growing aspirations of the committee members who decided to accept the offer to move to the Molineux Leisure Grounds, and so the ‘legendary’ Molineux story began.

Prior to playing on the Dudley Road pitch, from 1881, Wolves had played on three other sites, starting at Windmill Field, Goldthorn Hill, from 1877 to 1879, then John Harper’s Field, Lower Villiers Street, from 1879 to 1881, and occasionally at the cricket ground of Blakenhall Wanderers, one of the founding clubs. The quality of all these pitches left a great deal to be desired, so now the team had a far better surface on which to match themselves against the best opposition in the new Football League.

However, before Wolves could move into their new home, the land between the house and the track had to be cleared of trees, fencing had to be removed and the bandstand had to be pulled down. The lake was drained and filled in and the iron bridge that spanned its narrowest point was dismantled. The brewery paid for the construction of players’ changing rooms, refurbished the existing three hundred-seat grandstand and built a shelter alongside this to house a further four thousand spectators on a raised embankment, with a further narrow cinder bank on the north side of the pitch. Thus, MOLINEUX was built and opened.

From the grandstand and the new embankments, the spectators watched ‘The Wolves’ beat ‘The Villa’ 1-0, with centre-forward Wykes scoring the winning goal with a low shot. Of course, there were no floodlights then, hence the 5.30 kick-off, allowing just enough time for the local supporters and players to walk or cycle there from work. Apparently, upon entering the ground, many could hardly recognise the place. The freshly-laid 115 x 75 yard pitch looked as level as a billiard-table. Chairman of the Wanderers Committee, Councillor Hollingsworth, kicked off for Wolves. After the game, seventy people, players, friends and officials, were entertained to dinner at the Molineux Hotel. Five days later, on a beautiful Saturday afternoon, at 4.20 p.m. (the game having been delayed by the late arrival of the visitors), Wolves kicked off their first League fixture at the ground.

From the grandstand and the new embankments, the spectators watched ‘The Wolves’ beat ‘The Villa’ 1-0, with centre-forward Wykes scoring the winning goal with a low shot. Of course, there were no floodlights then, hence the 5.30 kick-off, allowing just enough time for the local supporters and players to walk or cycle there from work. Apparently, upon entering the ground, many could hardly recognise the place. The freshly-laid 115 x 75 yard pitch looked as level as a billiard-table. Chairman of the Wanderers Committee, Councillor Hollingsworth, kicked off for Wolves. After the game, seventy people, players, friends and officials, were entertained to dinner at the Molineux Hotel. Five days later, on a beautiful Saturday afternoon, at 4.20 p.m. (the game having been delayed by the late arrival of the visitors), Wolves kicked off their first League fixture at the ground.

Their opponents that day were Notts County, whom they beat 2-0. Once again, the turn-out was below capacity, at only four thousand. This shows that ‘Association Football’ had not yet captured the imagination of the people of Wolverhampton, especially with the cricket season not yet over. Throughout the first part of that season, the ‘gates’ only rarely reached five thousand, but the Boxing Day match against Blackburn Rovers attracted nineteen thousand, vindicating the faith of both the Committee and Butler’s brewery. Interestingly, yesterday’s clash (30 August 2014) with Blackburn in the Football League Championship attracted just over 21,000 to the new all-seater Molineux, whose capacity is 32,000. Wolves went on to reach the semi-final of the FA Cup in their first season at Molineux, and eventually won the FA Cup in 1893, reaching the final again in 1896.

During these pioneering years, the Molineux Hotel hosted a number of meetings for the Football League, and in March 1891 the ground played host to England’s international with Ireland, which the home nation won 6-1. It was also chosen to host the 1892 FA Cup semi-final, and three more semi-finals and a further international match followed, but its basic facilities for spectators soon fell behind those of its neighbours, including West Bromwich Albion. It changed little until a curved roof was built over half of the north end, in 1911, made from corrugated iron, earning it the nickname ‘the Cowshed’, which was where I stood as a boy, the name still in use then, despite the demolition of the original structure in the 1920s.

Molineux in the Twentieth Century

In 1923, the club bought the Molineux freehold from the brewery and Wolverhampton Wanderers Limited came into being. However, they had to wait another thirty years to win the old First Division Championship (now replaced by the ‘Premiership’). Following their title-winning season in 1953-54, Wolves played hosts to a number of European club sides under the new floodlights at Molineux. The most famous of these was the game against Budapest Honved, the crack team of the Hungarian Army, eight of whom, including captain Ferenc Puskás, had been in the team which had beaten England 6-3 at Wembley (the first time England had lost to a continental side on home soil), and 7-1 in Budapest in the previous season.

In 1923, the club bought the Molineux freehold from the brewery and Wolverhampton Wanderers Limited came into being. However, they had to wait another thirty years to win the old First Division Championship (now replaced by the ‘Premiership’). Following their title-winning season in 1953-54, Wolves played hosts to a number of European club sides under the new floodlights at Molineux. The most famous of these was the game against Budapest Honved, the crack team of the Hungarian Army, eight of whom, including captain Ferenc Puskás, had been in the team which had beaten England 6-3 at Wembley (the first time England had lost to a continental side on home soil), and 7-1 in Budapest in the previous season.

T he Hungarian national team should have won the World Cup that summer in Switzerland, but were beaten in the final by a West German side which came from 2-0 down at half-time to win 3-2. The England team did not meet the Hungarians in the finals, so this club match at Molineux was billed as the chance for revenge for Billy Wright (Wolves and England captain) and his boys. Again, Honved went 2-0 up in the first quarter of an hour, but Wolves came back to win 3-2 in a match which was televised live (my cousin watched it in his national service barracks). The Hungarian uprising of 1956 put paid to this magnificent Magyar team, who were touring at the time, but two years later, almost to the day, a benefit match was played, again floodlit, with MTK (Red Banner) Budapest. The team included Hidegkuti at centre-forward, and three other internationals, and raised 2,300 pounds for the Hungarian Relief Fund. The 1-1 scoreline was largely irrelevant, and the match did not live up to the heritage of the Hungarians, no matter how hard they tried, though Hidegkuti and Palotas combined brilliantly at times. What may better be remembered was the speech of the Wolves Chairman, James Baker, at the pre-match banquet, when he referred to the Wolves’ motto ‘out of darkness cometh light’, and hoped that very soon that would be the way in their native land.

he Hungarian national team should have won the World Cup that summer in Switzerland, but were beaten in the final by a West German side which came from 2-0 down at half-time to win 3-2. The England team did not meet the Hungarians in the finals, so this club match at Molineux was billed as the chance for revenge for Billy Wright (Wolves and England captain) and his boys. Again, Honved went 2-0 up in the first quarter of an hour, but Wolves came back to win 3-2 in a match which was televised live (my cousin watched it in his national service barracks). The Hungarian uprising of 1956 put paid to this magnificent Magyar team, who were touring at the time, but two years later, almost to the day, a benefit match was played, again floodlit, with MTK (Red Banner) Budapest. The team included Hidegkuti at centre-forward, and three other internationals, and raised 2,300 pounds for the Hungarian Relief Fund. The 1-1 scoreline was largely irrelevant, and the match did not live up to the heritage of the Hungarians, no matter how hard they tried, though Hidegkuti and Palotas combined brilliantly at times. What may better be remembered was the speech of the Wolves Chairman, James Baker, at the pre-match banquet, when he referred to the Wolves’ motto ‘out of darkness cometh light’, and hoped that very soon that would be the way in their native land.

‘Fast-forward’ nearly forty years, to December 1993, and the Hungarians were again in town, having emerged from more than three decades of ‘darkness’ into the light in 1989. To mark the opening of the stand completing the ‘new Molineux’ on 7 December 1993, a capacity crowd of 28,245 watched the visitors, Kispest Honved, hold Wolves to a 2-2 draw. For the first time in nine years, Molineux was once more a four-sided stadium. Interestingly, just prior to kick-off there was a short delay due to problems with the floodlighting. Once again, the message went out (with a touch of Black Country humour this time!): ‘Nothing to worry about, for as all Wolves fans know – Out of Darkness Cometh Light!’ In this 1993/94 season, on the fiftieth anniversary of their first floodlit games at Molineux, it was fitting that Wolverhampton Wanderers were back again in the top flight of English football.

‘Fast-forward’ nearly forty years, to December 1993, and the Hungarians were again in town, having emerged from more than three decades of ‘darkness’ into the light in 1989. To mark the opening of the stand completing the ‘new Molineux’ on 7 December 1993, a capacity crowd of 28,245 watched the visitors, Kispest Honved, hold Wolves to a 2-2 draw. For the first time in nine years, Molineux was once more a four-sided stadium. Interestingly, just prior to kick-off there was a short delay due to problems with the floodlighting. Once again, the message went out (with a touch of Black Country humour this time!): ‘Nothing to worry about, for as all Wolves fans know – Out of Darkness Cometh Light!’ In this 1993/94 season, on the fiftieth anniversary of their first floodlit games at Molineux, it was fitting that Wolverhampton Wanderers were back again in the top flight of English football.

Twenty seasons later, and Wolves are already in third place in the Championship, promising an early return to the Premiership, after dropping two divisions and gaining promotion last season. Let’s hope that after celebrating 125 years at Molinuex, Wolves can again return to the top flight, where a club with such a great history as theirs, truly belongs. But then, success in the modern game is no longer based on heritage and tradition, if it ever was.

Twenty seasons later, and Wolves are already in third place in the Championship, promising an early return to the Premiership, after dropping two divisions and gaining promotion last season. Let’s hope that after celebrating 125 years at Molinuex, Wolves can again return to the top flight, where a club with such a great history as theirs, truly belongs. But then, success in the modern game is no longer based on heritage and tradition, if it ever was.

Printed Source:

John Shipley (2003), Wolves Against the World: European Nights, 1953-1980. Stroud: Tempus Publishing.

The family residence in Tup Street, Wolverhampton, which became known as ‘Mr Molineuxe’s Close’, came into the possession of the family in 1744 after the death of the original owner, John Rotton, who owed Benjamin Molineux £700. The beneficiaries of his will (his wife, and his business partner Richard Wilkes), agreed to sell the property, and around eight acres of surrounding land, to the Molineux family to pay off the debt. Little is known about the original property, which was probably built around 1720.

The family residence in Tup Street, Wolverhampton, which became known as ‘Mr Molineuxe’s Close’, came into the possession of the family in 1744 after the death of the original owner, John Rotton, who owed Benjamin Molineux £700. The beneficiaries of his will (his wife, and his business partner Richard Wilkes), agreed to sell the property, and around eight acres of surrounding land, to the Molineux family to pay off the debt. Little is known about the original property, which was probably built around 1720.  The Molineux family extended the house, and added a fine rear extension, which looked even better than the main façade. What is certain that by 1750 work had finished on the house, and the rear formal garden, because they appear on Isaac Taylor’s map (see opposite), which was drawn during that year. By the time the ‘Tithe Map’ was published, in 1842, it had become known as ‘Molineux House’. It stood proudly on a hill overlooking extensive gardens, with delightful views of the Clee Hills and the Wrekin, together with panoramic views of Chillington and the woods. one of the largest houses in the town.

The Molineux family extended the house, and added a fine rear extension, which looked even better than the main façade. What is certain that by 1750 work had finished on the house, and the rear formal garden, because they appear on Isaac Taylor’s map (see opposite), which was drawn during that year. By the time the ‘Tithe Map’ was published, in 1842, it had become known as ‘Molineux House’. It stood proudly on a hill overlooking extensive gardens, with delightful views of the Clee Hills and the Wrekin, together with panoramic views of Chillington and the woods. one of the largest houses in the town. So it was that the estate was bought in 1860 by Mr O E McGregor, obviously another man with a vision. He retained the name ‘Molineux Grounds’, spending seven thousand pounds on returning the house to its former glory, and converting the rest of the estate into a pleasure park, which he then opened to the public for a small admission fee. The ‘Grounds’, the first park of its kind in Wolverhampton, boasted a number of different attractions, including a skating rink, a boating lake with fountain, croquet lawns, flower-beds, walkways and lawns, plus amenities for football and cricket, and soon became established as a popular place of recreation, with many fetes and galas being held there, including the 1869 South Staffordshire Industrial and Fine Arts Exhibition.

So it was that the estate was bought in 1860 by Mr O E McGregor, obviously another man with a vision. He retained the name ‘Molineux Grounds’, spending seven thousand pounds on returning the house to its former glory, and converting the rest of the estate into a pleasure park, which he then opened to the public for a small admission fee. The ‘Grounds’, the first park of its kind in Wolverhampton, boasted a number of different attractions, including a skating rink, a boating lake with fountain, croquet lawns, flower-beds, walkways and lawns, plus amenities for football and cricket, and soon became established as a popular place of recreation, with many fetes and galas being held there, including the 1869 South Staffordshire Industrial and Fine Arts Exhibition. By 1872, the grounds had been further developed to include a number of other attractions, and the arena facilities were used to stage a number of sporting events including cycle racing, football and cricket matches. When, subsequently, Northampton Brewery acquired the entire site, they converted Molineux House into a hotel and, in 1889 rented the grounds to Wolverhampton Wanderers for a very low annual rent of fifty pounds.

By 1872, the grounds had been further developed to include a number of other attractions, and the arena facilities were used to stage a number of sporting events including cycle racing, football and cricket matches. When, subsequently, Northampton Brewery acquired the entire site, they converted Molineux House into a hotel and, in 1889 rented the grounds to Wolverhampton Wanderers for a very low annual rent of fifty pounds. The Wolves had first played a game on ‘The Molineux Grounds’, as they were then known, in 1886, losing 2-1 to their neighbours, Walsall Town in the final of the Walsall Cup. In 1888, the club reached its first FA Cup final, losing 1-0 to Preston North End. The new grounds matched the growing aspirations of the committee members who decided to accept the offer to move to the Molineux Leisure Grounds, and so the ‘legendary’ Molineux story began.

The Wolves had first played a game on ‘The Molineux Grounds’, as they were then known, in 1886, losing 2-1 to their neighbours, Walsall Town in the final of the Walsall Cup. In 1888, the club reached its first FA Cup final, losing 1-0 to Preston North End. The new grounds matched the growing aspirations of the committee members who decided to accept the offer to move to the Molineux Leisure Grounds, and so the ‘legendary’ Molineux story began. From the grandstand and the new embankments, the spectators watched ‘The Wolves’ beat ‘The Villa’ 1-0, with centre-forward Wykes scoring the winning goal with a low shot. Of course, there were no floodlights then, hence the 5.30 kick-off, allowing just enough time for the local supporters and players to walk or cycle there from work. Apparently, upon entering the ground, many could hardly recognise the place. The freshly-laid 115 x 75 yard pitch looked as level as a billiard-table. Chairman of the Wanderers Committee, Councillor Hollingsworth, kicked off for Wolves. After the game, seventy people, players, friends and officials, were entertained to dinner at the Molineux Hotel. Five days later, on a beautiful Saturday afternoon, at 4.20 p.m. (the game having been delayed by the late arrival of the visitors), Wolves kicked off their first League fixture at the ground.

From the grandstand and the new embankments, the spectators watched ‘The Wolves’ beat ‘The Villa’ 1-0, with centre-forward Wykes scoring the winning goal with a low shot. Of course, there were no floodlights then, hence the 5.30 kick-off, allowing just enough time for the local supporters and players to walk or cycle there from work. Apparently, upon entering the ground, many could hardly recognise the place. The freshly-laid 115 x 75 yard pitch looked as level as a billiard-table. Chairman of the Wanderers Committee, Councillor Hollingsworth, kicked off for Wolves. After the game, seventy people, players, friends and officials, were entertained to dinner at the Molineux Hotel. Five days later, on a beautiful Saturday afternoon, at 4.20 p.m. (the game having been delayed by the late arrival of the visitors), Wolves kicked off their first League fixture at the ground. In 1923, the club bought the Molineux freehold from the brewery and Wolverhampton Wanderers Limited came into being. However, they had to wait another thirty years to win the old First Division Championship (now replaced by the ‘Premiership’). Following their title-winning season in 1953-54, Wolves played hosts to a number of European club sides under the new floodlights at Molineux. The most famous of these was the game against Budapest Honved, the crack team of the Hungarian Army, eight of whom, including captain Ferenc Puskás, had been in the team which had beaten England 6-3 at Wembley (the first time England had lost to a continental side on home soil), and 7-1 in Budapest in the previous season.

In 1923, the club bought the Molineux freehold from the brewery and Wolverhampton Wanderers Limited came into being. However, they had to wait another thirty years to win the old First Division Championship (now replaced by the ‘Premiership’). Following their title-winning season in 1953-54, Wolves played hosts to a number of European club sides under the new floodlights at Molineux. The most famous of these was the game against Budapest Honved, the crack team of the Hungarian Army, eight of whom, including captain Ferenc Puskás, had been in the team which had beaten England 6-3 at Wembley (the first time England had lost to a continental side on home soil), and 7-1 in Budapest in the previous season. he Hungarian national team should have won the World Cup that summer in Switzerland, but were beaten in the final by a West German side which came from 2-0 down at half-time to win 3-2. The England team did not meet the Hungarians in the finals, so this club match at Molineux was billed as the chance for revenge for Billy Wright (Wolves and England captain) and his boys. Again, Honved went 2-0 up in the first quarter of an hour, but Wolves came back to win 3-2 in a match which was televised live (my cousin watched it in his national service barracks). The Hungarian uprising of 1956 put paid to this magnificent Magyar team, who were touring at the time, but two years later, almost to the day, a benefit match was played, again floodlit, with MTK (Red Banner) Budapest. The team included Hidegkuti at centre-forward, and three other internationals, and raised 2,300 pounds for the Hungarian Relief Fund. The 1-1 scoreline was largely irrelevant, and the match did not live up to the heritage of the Hungarians, no matter how hard they tried, though Hidegkuti and Palotas combined brilliantly at times. What may better be remembered was the speech of the Wolves Chairman, James Baker, at the pre-match banquet, when he referred to the Wolves’ motto ‘out of darkness cometh light’, and hoped that very soon that would be the way in their native land.

he Hungarian national team should have won the World Cup that summer in Switzerland, but were beaten in the final by a West German side which came from 2-0 down at half-time to win 3-2. The England team did not meet the Hungarians in the finals, so this club match at Molineux was billed as the chance for revenge for Billy Wright (Wolves and England captain) and his boys. Again, Honved went 2-0 up in the first quarter of an hour, but Wolves came back to win 3-2 in a match which was televised live (my cousin watched it in his national service barracks). The Hungarian uprising of 1956 put paid to this magnificent Magyar team, who were touring at the time, but two years later, almost to the day, a benefit match was played, again floodlit, with MTK (Red Banner) Budapest. The team included Hidegkuti at centre-forward, and three other internationals, and raised 2,300 pounds for the Hungarian Relief Fund. The 1-1 scoreline was largely irrelevant, and the match did not live up to the heritage of the Hungarians, no matter how hard they tried, though Hidegkuti and Palotas combined brilliantly at times. What may better be remembered was the speech of the Wolves Chairman, James Baker, at the pre-match banquet, when he referred to the Wolves’ motto ‘out of darkness cometh light’, and hoped that very soon that would be the way in their native land. ‘Fast-forward’ nearly forty years, to December 1993, and the Hungarians were again in town, having emerged from more than three decades of ‘darkness’ into the light in 1989. To mark the opening of the stand completing the ‘new Molineux’ on 7 December 1993, a capacity crowd of 28,245 watched the visitors, Kispest Honved, hold Wolves to a 2-2 draw. For the first time in nine years, Molineux was once more a four-sided stadium. Interestingly, just prior to kick-off there was a short delay due to problems with the floodlighting. Once again, the message went out (with a touch of Black Country humour this time!): ‘Nothing to worry about, for as all Wolves fans know – Out of Darkness Cometh Light!’ In this 1993/94 season, on the fiftieth anniversary of their first floodlit games at Molineux, it was fitting that Wolverhampton Wanderers were back again in the top flight of English football.

‘Fast-forward’ nearly forty years, to December 1993, and the Hungarians were again in town, having emerged from more than three decades of ‘darkness’ into the light in 1989. To mark the opening of the stand completing the ‘new Molineux’ on 7 December 1993, a capacity crowd of 28,245 watched the visitors, Kispest Honved, hold Wolves to a 2-2 draw. For the first time in nine years, Molineux was once more a four-sided stadium. Interestingly, just prior to kick-off there was a short delay due to problems with the floodlighting. Once again, the message went out (with a touch of Black Country humour this time!): ‘Nothing to worry about, for as all Wolves fans know – Out of Darkness Cometh Light!’ In this 1993/94 season, on the fiftieth anniversary of their first floodlit games at Molineux, it was fitting that Wolverhampton Wanderers were back again in the top flight of English football. Twenty seasons later, and Wolves are already in third place in the Championship, promising an early return to the Premiership, after dropping two divisions and gaining promotion last season. Let’s hope that after celebrating 125 years at Molinuex, Wolves can again return to the top flight, where a club with such a great history as theirs, truly belongs. But then, success in the modern game is no longer based on heritage and tradition, if it ever was.

Twenty seasons later, and Wolves are already in third place in the Championship, promising an early return to the Premiership, after dropping two divisions and gaining promotion last season. Let’s hope that after celebrating 125 years at Molinuex, Wolves can again return to the top flight, where a club with such a great history as theirs, truly belongs. But then, success in the modern game is no longer based on heritage and tradition, if it ever was.

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.