The Failed Coup that ended Communist Rule

In August, holiday-time, Gorbachev went to his villa at Foros on the Black Sea. In June the old-guard Communists had tried, unsuccessfully, to unseat him by constitutional means in the Congress of People’s Deputies. Now they attempted to remove him by force. In Moscow, early in the morning of 19 August, as Gorbachev’s holiday was drawing to a close, radio and tv began broadcasting a statement by the State Committee for the State of Emergency. It claimed that the President was ill and unable to perform his duties; Vice-President Yanayev had assumed the powers of the Presidency, and a state of emergency had been declared. It was a coup, but to the ordinary citizens of Moscow and Leningrad, this was, as yet, unclear. Information about Gorbachev’s whereabouts and state of health was hard to come by. The television schedule kept changing, with the ballet Swan Lake replacing the usual diet of news bulletins.

The true story was that the previous day, Sunday 18th August, a delegation from Moscow had arrived at the seaside villa to see Gorbachev. Before they were admitted, he tried to telephone out, but the phone lines had already been cut. At sea, naval craft manoeuvred menacingly near the shore. The conspirators pushed their way in: Oleg Baklanov, Gorbachev’s deputy at the Defence Council; Party Secretary Oleg Shenin; Deputy Defence Minister General Valentin Varennikov; Gorbachev’s Chief of Staff, Valery Boldin. They tried to force the President to approve the declaration of a state of emergency, to resign and to hand over his authority to Yanayev. Gorbachev refused, for to do otherwise would have legitimised the plot. They put him under house arrest, cut off from communication with the outside world, and left.

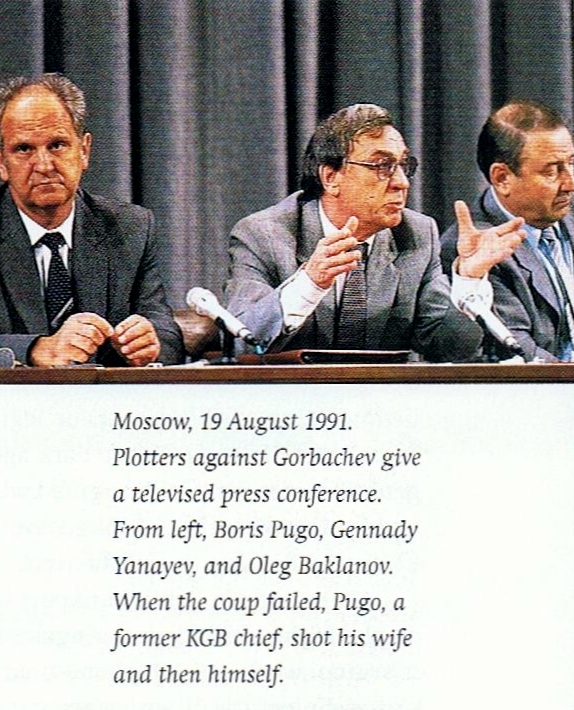

The plotters included several other members of the government: Prime Minister Pavlov; KGB Chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov; Interior Minister Pugo; Minister of Defence Minister Dmitry Yazov. Most of them had been urging Gorbachev for months to impose emergency rule. Now they imposed it themselves, and hoped he would go along with it. He had underestimated their strength; they had underestimated their his determination to resist. His refusal to give in was brave, but the real struggle was to be in Moscow.

In every Moscow ministry and in the republics, every civil servant had to make up his or her mind what to do. Most temporised and waited to see how things would turn out. Enough of them, together with those in the military and the KGB refused to obey orders from the Emergency Committee to ensure that the coup would not succeed. Gorbachev’s insistence on moving towards democracy was paying off. Resistance was led from the White House, the seat of the Russian Parliament, by Boris Yeltsin. Usually at odds with Gorbachev, stood firm. He denounced the coup and those behind it, rallying support for legitimate government and a liberal future rather than a return to the dark ages of totalitarian tyranny. He called for a general strike, so that those who had the courage to support him went to the White House, ringed by troops and tanks, to declare their support. Eduard Shevardnadze was one of the first to arrive.

President Bush was also on holiday in Kennebunkport in Maine, where he had gone to bed on the Sunday night of Gorbachev’s ‘arrest’. When the telephone rang with the news from Moscow, he faced a classic diplomatic dilemma as to what he would say in his statement early the next day. It was agreed that he would talk to the press early the next morning, and he met them at eight, praising Gorbachev as a “historic figure”, hedging on Yanayev and stopping short of outright denunciation when he called the seizure of power “extra-constitutional.” He insisted that the US reaction would aim not to “over-excite the American people or the world… we will conduct our diplomacy in a prudent fashion, not driven by excess.” It was not much more than wait and see.

At Foros, the Gorbachevs were listening to events in Moscow on the BBC World Service, using a transistor radio which their captors had failed to confiscate. Raisa recorded her indignation in her diary at the reporting on state television. Kazakhstan’s President, Nursultan Nazarbayev, was reported to have appealed to the people of his republic “to remain calm and cool and maintain public order. She noted that there was “not a word about the ousting of the President of the USSR.” Her husband sent a message to Yanayev: Cancel what you’ve done and convene the Congress of People’s Deputies or the USSR’s Supreme Soviet.

On the night of 20 August, the first blood was spilt. Three young men were killed by armoured personnel carriers moving towards the White House in support of the coup. Had the Emergency Committee been more resolute, many more lives would certainly have been lost. They were hesitant, however, unsure of themselves and their supporters, perhaps even of their cause. The coup had already failed, but in the rest of eastern Europe and beyond, this had not become clear. In Hungary, many families were away from home at their weekend houses, enjoying St Stephen’s Day, the national holiday and listening occasionally to their transistors, dreading the prospect that the recently withdrawn Soviet troops would soon be rolling back into their country, as they had done in 1956. I remember being on holiday with my father-in-law, who was firm in his view that this was more than a possibility if the coup succeeded.

It was announced the following day that a delegation would be permitted to leave Moscow for the Crimea to see for themselves that Gorbachev was gravely ill. At Foros this caused alarm. The couple was already boiling all the food they were given in case of poisoning. Would the plotters now try to make to make their statements come true and somehow bring about Gorbachev’s death? Meanwhile, back in Moscow, crowds surrounded the Russian Parliament building, where Boris Yeltsin led the resistance against the unconstitutional coup (pictured above). The delegation, which actually wanted to negotiate, reached Foros at 5 p.m. and asked to see Gorbachev. It included Kryuchkov, Yazov, Baklanov, and Anatoli Lukyanov, chairman of the Supreme Soviet. Gorbachev refused to see them until proper communications were restored. At 5:45 p.m., the telephones were reconnected. Gorbachev rang Yeltsin who said:

Mikhail Sergeyevich, my dear man, are you alive? We have been holding firm here for forty-eight hours.

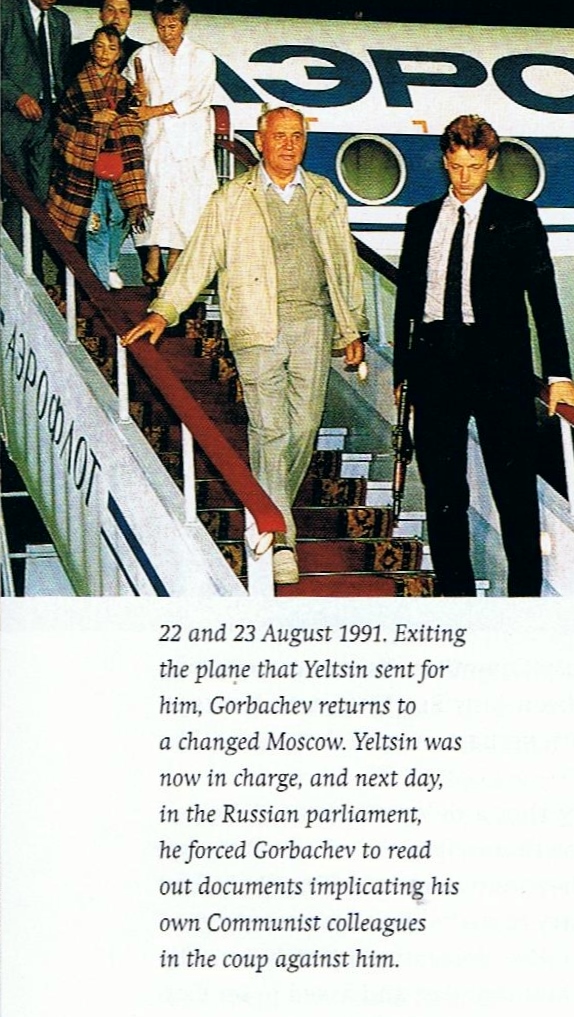

Shortly afterwards, a Russian delegation arrived, led by Alexander Rutskoi, Yeltsin’s Vice-President, to bring Gorbachev and his family back to Moscow. Without packing, they prepared to leave. Later, Kryuchkov wrote to Gorbachev, expressing remorse; Yazov, with his excellent military record, confessed that he had made an ass of himself; Lukyanov had no good answer to Gorbachev’s question: “Why did you not exercise your own constitutional powers?” In Moscow, Yanayev took to the bottle; Pugo shot his wife and then himself when the loyalists came to arrest him; Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev, Gorbachev’s military advisor, also committed suicide. He left a note stating, “everything I have worked for is being destroyed.” Bessmertnykh, who had been careful not to commit himself either way, had to resign. When Gorbachev returned to Moscow on 22 August, he made a spontaneous statement:

I have come back from Foros to another country, and I myself am a different man now.

However, the restored President soon gave the impression that he thought things could carry on as before, even reaffirming his belief in the Communist Party and its renewal. This was not what many in Moscow needed to hear as, on 23 August, Gorbachev was first jeered in the Russian Parliament and then humiliated when Yeltsin, without warning, put into his hand a set of minutes he had not seen before and forced him to read them out loud on live television. The document implicated his own Communist colleagues in the coup against him. Yeltsin was now in charge in Moscow and both Russian viewers and US diplomats watching these pictures knew that Gorbachev was finished, destroyed by a failed coup.

By this time, Gorbachev had also lost power away from Moscow, in the republics. On the 20 and 21 August, Estonia and Latvia declared independence, joining Lithuania, which had declared its freedom from the USSR in 1990, which it now reaffirmed. The republics of Ukraine, Belarus, Moldavia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kirghizia, Tadzhikistan, and Armenia, all followed suit soon after. On 24 August, Gorbachev resigned as leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, disbanding the Central Committee. On 29 August, the Soviet Communist Party effectively dissolved itself. After seven decades, Soviet Communism, as an ideology and a political organism, was on its death-bed. Meanwhile, the Russian tricolour was paraded in mourning for those few who died during the failed coup.

Source:

Jeremy Isaacs & Taylor Downing (1998), Cold War. London: Transworld Publishers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.