Archive for the ‘Caribbean’ Tag

Cold Shoulder or Warm Handshake?

On 29 March 2019, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland will leave the European Union after forty-six years of membership, since it joined the European Economic Community on 1 January 1973 on the same day and hour as the Republic of Ireland. Yet in 1999, it looked as if the long-standing debate over Britain’s membership had been resolved. The Maastricht Treaty establishing the European Union had been signed by all the member states of the preceding European Community in February 1992 and was succeeded by a further treaty, signed in Amsterdam in 1999. What, then, has happened in the space of twenty years to so fundamentally change the ‘settled’ view of the British Parliament and people, bearing in mind that both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU, while England and Wales both voted to leave? At the time of writing, the manner of our going has not yet been determined, but the invocation of ‘article fifty’ by the Westminster Parliament and the UK government means that the date has been set. So either we will have to leave without a deal, turning a cold shoulder to our erstwhile friends and allies on the continent, or we will finally ratify the deal agreed between the EU Commission, on behalf of the twenty-seven remaining member states, and leave with a warm handshake and most of our trading and cultural relations intact.

As yet, the possibility of a second referendum – or third, if we take into account the 1975 referendum, called by Harold Wilson (above) which was also a binary leave/ remain decision – seems remote. In any event, it is quite likely that the result would be the same and would kill off any opportunity of the UK returning to EU membership for at least another generation. As Ian Fleming’s James Bond tells us, ‘you only live twice’. That certainly seems to be the mood in Brussels too. I was too young to vote in 1975 by just five days, and another membership referendum would be unlikely to occur in my lifetime. So much has been said about following ‘the will of the people’, or at least 52% of them, that it would be a foolish government, in an age of rampant populism, that chose to revoke article fifty, even if Westminster voted for this. At the same time, and in that same populist age, we know from recent experience that in politics and international relations, nothing is inevitable…

![referendum-ballot-box[1]](https://chandlerozconsultants.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/referendum-ballot-box11.jpg?w=328&h=185)

One of the major factors in the 2016 Referendum Campaign was the country’s public spending priorities, compared with those of the European Union. The ‘Leave’ campaign sent a double-decker bus around England stating that by ending the UK’s payments into the EU, more than 350 million pounds per week could be redirected to the National Health Service (NHS).

A British Icon Revived – The NHS under New Labour:

To understand the power of this statement, it is important to recognise that the NHS is unique in Europe in that it is wholly funded from direct taxation, and not via National Insurance, as in many other European countries. As a service created in 1948 to be ‘free at the point of delivery’, it is seen as a ‘British icon’ and funding has been a central issue in national election campaigns since 2001, when Tony Blair was confronted by an irate voter, Sharon Storer, outside a hospital. In its first election manifesto of 1997, ‘New Labour’ promised to safeguard the basic principles of the NHS, which we founded. The ‘we’ here was the post-war Labour government, whose socialist Health Minister, Aneurin Bevan, had established the service in the teeth of considerable opposition from within both parliament and the medical profession. ‘New Labour’ protested that under the Tories there had been fifty thousand fewer nurses but a rise of no fewer than twenty thousand managers – red tape which Labour would pull away and burn. Though critical of the internal markets the Tories had introduced, Blair promised to keep a split between those who commissioned health services and those who provided them.

Under Frank Dobson, Labour’s new Health Secretary, there was little reform of the NHS but there was, year by year, just enough extra money to stave off the winter crises. But then a series of tragic individual cases hit the headlines, and one of them came from a Labour peer and well-known medical scientist and fertility expert, Professor Robert Winston, who was greatly admired by Tony Blair. He launched a furious denunciation of the government over the treatment of his elderly mother. Far from upholding the NHS’s iconic status, Winston said that Britain’s health service was the worst in Europe and was getting worse under the New Labour government, which was being deceitful about the true picture. Labour’s polling on the issue showed that Winston was, in general terms, correct in his assessment in the view of the country as a whole. In January 2000, therefore, Blair announced directly to it that he would bring Britain’s health spending up to the European average within five years. That was a huge promise because it meant spending a third as much again in real terms, and his ‘prudent’ Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, was unhappy that Blair had not spoken enough on television about the need for health service reform to accompany the money, and had also ‘stolen’ his budget announcements. On Budget day itself, Brown announced that until 2004 health spending would rise at above six per cent beyond inflation every year, …

… by far the largest sustained increase in NHS funding in any period in its fifty-year history … half as much again for health care for every family in this country.

The tilt away from Brown’s sharp spending controls during the first three years of the New Labour government had begun by the first spring of the new millennium, and there was more to come. With a general election looming in 2001, Brown also announced a review of the NHS and its future by a former banker. As soon as the election was over, broad hints about necessary tax rises were dropped. When the Wanless Report was finally published, it confirmed much that the winter crisis of 1999-2000 had exposed. The NHS was not, whatever Britons fondly believed, better than health systems in other developed countries, and it needed a lot more money. ‘Wanless’ also rejected a radical change in funding, such as a switch to insurance-based or semi-private health care. Brown immediately used this as objective proof that taxes had to rise in order to save the NHS. In his next budget of 2002, Brown broke with a political convention that which had reigned since the mid-eighties, that direct taxes would not be raised again. He raised a special one per cent national insurance levy, equivalent to a penny on income tax, to fund the huge reinvestment in Britain’s health.

Public spending shot up with this commitment and, in some ways, it paid off, since by 2006 there were around 300,000 extra NHS staff compared to 1997. That included more than ten thousand extra senior hospital doctors (about a quarter more) and 85,000 more nurses. But there were also nearly forty thousand managers, twice as many as Blair and Brown had ridiculed the Tory government for hiring. An ambitious computer project for the whole NHS became an expensive catastrophe. Meanwhile, the health service budget rose from thirty-seven billion to more than ninety-two billion a year. But the investment produced results, with waiting lists, a source of great public anger from the mid-nineties, falling by 200,000. By 2005, Blair was able to talk of the best waiting list figures since 1988. Hardly anyone was left waiting for an inpatient appointment for more than six months. Death rates from cancer for people under the age of seventy-five fell by 15.7 per cent between 1996 and 2006 and death rates from heart disease fell by just under thirty-six per cent. Meanwhile, the public finance initiative meant that new hospitals were being built around the country. But, unfortunately for New Labour, that was not the whole story of the Health Service under their stewardship. As Andrew Marr has attested,

…’Czars’, quangos, agencies, commissions, access teams and planners hunched over the NHS as Whitehall, having promised to devolve power, now imposed a new round of mind-dazing control.

By the autumn of 2004 hospitals were subject to more than a hundred inspections. War broke out between Brown and the Treasury and the ‘Blairite’ Health Secretary, Alan Milburn, about the basic principles of running the hospitals. Milburn wanted more competition between them, but Brown didn’t see how this was possible when most people had only one major local hospital. Polling suggested that he was making a popular point. Most people simply wanted better hospitals, not more choice. A truce was eventually declared with the establishment of a small number of independent, ‘foundation’ hospitals. By the 2005 general election, Michael Howard’s Conservatives were attacking Labour for wasting money and allowing people’s lives to be put at risk in dirty, badly run hospitals. Just like Labour once had, they were promising to cut bureaucracy and the number of organisations within the NHS. By the summer of 2006, despite the huge injection of funds, the Service was facing a cash crisis. Although the shortfall was not huge as a percentage of the total budget, trusts in some of the most vulnerable parts of the country were on the edge of bankruptcy, from Hartlepool to Cornwall and across to London. Throughout Britain, seven thousand jobs had gone and the Royal College of Nursing, the professional association to which most nurses belonged, was predicting thirteen thousand more would go soon. Many newly and expensively qualified doctors and even specialist consultants could not find work. It seemed that wage costs, expensive new drugs, poor management and the money poured into endless bureaucratic reforms had resulted in a still inadequate service. Bupa, the leading private operator, had been covering some 2.3 million people in 1999. Six years later, the figure was more than eight million. This partly reflected greater affluence, but it was also hardly a resounding vote of confidence in Labour’s management of the NHS.

Public Spending, Declining Regions & Economic Development:

As public spending had begun to flow during the second Blair administration, vast amounts of money had gone in pay rises, new bureaucracies and on bills for outside consultants. Ministries had been unused to spending again, after the initial period of ‘prudence’, and did not always do it well. Brown and his Treasury team resorted to double and triple counting of early spending increases in order to give the impression they were doing more for hospitals, schools and transport than they actually could. As Marr has pointed out, …

… In trying to achieve better policing, more effective planning, healthier school food, prettier town centres and a hundred other hopes, the centre of government ordered and cajoled, hassled and harangued, always high-minded, always speaking for ‘the people’.

The railways, after yet another disaster, were shaken up again. In very controversial circumstances Railtrack, the once-profitable monopoly company operating the lines, was driven to bankruptcy and a new system of Whitehall control was imposed. At one point, Tony Blair boasted of having five hundred targets for the public sector. Parish councils, small businesses and charities found that they were loaded with directives. Schools and hospitals had many more. Marr has commented, …

The interference was always well-meant but it clogged up the arteries of free decision-taking and frustrated responsible public life.

Throughout the New Labour years, with steady growth and low inflation, most of the country grew richer. Growth since 1997, at 2.8 per cent per year, was above the post-war average, GDP per head was above that of France and Germany and the country had the second lowest jobless figures in the EU. The number of people in work increased by 2.4 million. Incomes grew, in real terms, by about a fifth. Pensions were in trouble, but house price inflation soured, so the owners found their properties more than doubling in value and came to think of themselves as prosperous. By 2006 analysts were assessing the disposable wealth of the British at forty thousand pounds per household. However, the wealth was not spread geographically, averaging sixty-eight thousand in the south-east of England, but a little over thirty thousand in Wales and north-east England (see map above). But even in the historically poorer parts of the UK house prices had risen fast, so much so that government plans to bulldoze worthless northern terraces had to be abandoned when they started to regain value. Cheap mortgages, easy borrowing and high property prices meant that millions of people felt far better off, despite the overall rise in the tax burden. Cheap air travel gave the British opportunities for easy travel both to traditional resorts and also to every part of the European continent. British expatriates were able to buy properties across the French countryside and in southern Spain. Some even began to commute weekly to jobs in London or Manchester from Mediterranean villas, and regional airports boomed as a result.

The internet, also known as the ‘World-Wide Web’, which was ‘invented’ by the British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee at the end of 1989 (pictured right in 2014), was advancing from the colleges and institutions into everyday life by the mid- ‘noughties’. It first began to attract popular interest in the mid-nineties: Britain’s first internet café and magazine, reviewing a few hundred early websites, were both launched in 1994. The following year saw the beginning of internet shopping as a major pastime, with both ‘eBay’ and ‘Amazon’ arriving, though to begin with they only attracted tiny numbers of people.

The internet, also known as the ‘World-Wide Web’, which was ‘invented’ by the British computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee at the end of 1989 (pictured right in 2014), was advancing from the colleges and institutions into everyday life by the mid- ‘noughties’. It first began to attract popular interest in the mid-nineties: Britain’s first internet café and magazine, reviewing a few hundred early websites, were both launched in 1994. The following year saw the beginning of internet shopping as a major pastime, with both ‘eBay’ and ‘Amazon’ arriving, though to begin with they only attracted tiny numbers of people.

But the introduction of new forms of mail-order and ‘click and collect’ shopping quickly attracted significant adherents from different ‘demographics’. The growth of the internet led to a feeling of optimism, despite warnings that the whole digital world would collapse because of the inability of computers to cope with the last two digits in the year ‘2000’, which were taken seriously at the time. In fact, the ‘dot-com’ bubble was burst by its own excessive expansion, as with any bubble, and following a pause and a lot of ruined dreams, the ‘new economy’ roared on again. By 2000, according to the Office of National Statistics (ONS), around forty per cent of Britons had accessed the internet at some time. Three years later, nearly half of British homes were ‘online’. By 2004, the spread of ‘broadband’ connections had brought a new mass market in ‘downloading’ music and video. By 2006, three-quarters of British children had internet access at home.

Simultaneously, the rich of America, Europe and Russia began buying up parts of London, and then other ‘attractive’ parts of the country, including Edinburgh, the Scottish Highlands, Yorkshire and Cornwall. ‘Executive housing’ with pebbled driveways, brick facing and dormer windows, was growing across farmland and by rivers with no thought of flood-plain constraints. Parts of the country far from London, such as the English south-west and Yorkshire, enjoyed a ripple of wealth that pushed their house prices to unheard-of levels. From Leith to Gateshead, Belfast to Cardiff Bay, once-derelict shorefront areas were transformed. The nineteenth-century buildings in the Albert Dock in Liverpool (above) now house a maritime museum, an art gallery, shopping centre and television studio. It has also become a tourist attraction. For all the problems and disappointments, and the longer-term problems with their financing, new schools and public buildings sprang up – new museums, galleries, vast shopping complexes (see below), corporate headquarters in a biomorphic architecture of glass and steel, more imaginative and better-looking than their predecessors from the dreary age of concrete.

Supermarket chains exercised huge market power, offering cheap meat and dairy products into almost everyone’s budgets. Factory-made ready-meals were transported and imported by the new global air freight market and refrigerated trucks and lorries moving freely across a Europe shorn of internal barriers. Out-of-season fruit and vegetables, fish from the Pacific, exotic foods of all kinds and freshly cut flowers appeared in superstores everywhere. Hardly anyone was out of reach of a ‘Tesco’, a ‘Morrison’s’, a ‘Sainsbury’s’ or an ‘Asda’. By the mid-noughties, the four supermarket giants owned more than 1,500 superstores throughout the UK. They spread the consumption of goods that in the eighties and nineties had seemed like luxuries. Students had to take out loans in order to go to university but were far more likely to do so than previous generations, as well as to travel more widely on a ‘gap’ year, not just to study or work abroad.

Those ‘Left Behind’ – Poverty, Pensions & Public Order:

Materially, for the majority of people, this was, to use Marr’s term, a ‘golden age’, which perhaps helps to explain both why earlier real anger about earlier pension decisions and stealth taxes did not translate into anti-Labour voting in successive general elections. The irony is that in pleasing ‘Middle Englanders’, the Blair-Brown government lost contact with traditional Labour voters, especially in the North of Britain, who did not benefit from these ‘golden years’ to the same extent. Gordon Brown, from the first, made much of New Labour’s anti-poverty agenda, and especially child poverty. Since the launch of the Child Poverty Action Group, this latter problem had become particularly emotive. Labour policies took a million children out of relative poverty between 1997 and 2004, though the numbers rose again later. Brown’s emphasis was on the working poor and the virtue of work. So his major innovations were the national minimum wage, the ‘New Deal’ for the young unemployed, and the working families’ tax credit, as well as tax credits aimed at children. There was also a minimum income guarantee and a later pension credit, for poorer pensioners.

The minimum wage was first set at three pounds sixty an hour, rising year by year. In 2006 it was 5.35 an hour. Because the figures were low, it did not destroy the two million jobs as the Tories claimed it would. Neither did it produce higher inflation; employment continued to grow while inflation remained low. It even seemed to have cut red tape. By the mid-noughties, the minimum wage covered two million people, the majority of them women. Because it was updated ahead of rises in inflation rates, the wages of the poor also rose faster. It was so successful that even the Tories were forced to embrace it ahead of the 2005 election. The New Deal was funded by a windfall tax on privatised utility companies, and by 2000 Blair said it had helped a quarter of a million young people back into work, and it was being claimed as a major factor in lower rates of unemployment as late as 2005. But the National Audit Office, looking back on its effect in the first parliament, reckoned the number of under twenty-five-year-olds helped into real jobs was as low as 25,000, at a cost per person of eight thousand pounds. A second initiative was targeted at the babies and toddlers of the most deprived families. ‘Sure Start’ was meant to bring mothers together in family centres across Britain – 3,500 were planned for 2010, ten years after the scheme had been launched – and to help them to become more effective parents. However, some of the most deprived families failed to show up. As Andrew Marr wrote, back in 2007:

Poverty is hard to define, easy to smell. In a country like Britain, it is mostly relative. Though there are a few thousand people living rough or who genuinely do not have enough to keep them decently alive, and many more pensioners frightened of how they will pay for heating, the greater number of poor are those left behind the general material improvement in life. This is measured by income compared to the average and by this yardstick in 1997 there were three to four million children living in households of relative poverty, triple the number in 1979. This does not mean they were physically worse off than the children of the late seventies, since the country generally became much richer. But human happiness relates to how we see ourselves relative to those around us, so it was certainly real.

The Tories, now under new management in the shape of a media-marketing executive and old Etonian, David Cameron, also declared that they believed in this concept of relative poverty. After all, it was on their watch, during the Thatcher and Major governments, that it had tripled, which is why it was only towards the end of the New Labour governments that they could accept the definition of the left-of-centre Guardian columnist, Polly Toynbee. A world of ‘black economy’ work also remained below the minimum wage, in private care homes, where migrant servants were exploited, and in other nooks and crannies. Some 336,000 jobs remained on ‘poverty pay’ rates. Yet ‘redistribution of wealth’, a socialist phrase which had become unfashionable under New Labour lest it should scare away middle Englanders, was stronger in Brown’s Britain than in other major industrialised nations. Despite the growth of the super-rich, many of whom were immigrants anyway, overall equality increased in these years. One factor in this was the return to the means-testing of benefits, particularly for pensioners and through the working families’ tax credit, subsequently divided into a child tax credit and a working tax credit. This was a U-turn by Gordon Brown, who had opposed means-testing when in Opposition. As Chancellor, he concluded that if he was to direct scarce resources at those in real poverty, he had little choice.

Apart from the demoralising effect it had on pensioners, the other drawback to means-testing was that a huge bureaucracy was needed to track people’s earnings and to try to establish exactly what they should be getting in benefits. Billions were overpaid and as people did better and earned more from more stable employment, they then found themselves facing huge demands to hand back the money they had already spent. Thousands of extra civil servants were needed to deal with the subsequent complaints and the scheme became extremely expensive to administer. There were also controversial drives to oblige more disabled people back to work, and the ‘socially excluded’ were confronted by a range of initiatives designed to make them more middle class. Compared with Mrs Thatcher’s Victorian Values and Mr Major’s Back to Basics campaigns, Labour was supposed to be non-judgemental about individual behaviour. But a form of moralism did begin to reassert itself. Parenting classes were sometimes mandated through the courts and for the minority who made life hell for their neighbours on housing estates, Labour introduced the Anti-Social Behaviour Order (‘Asbo’). These were first given out in 1998, granted by magistrates to either the police or the local council. It became a criminal offence to break the curfew or other sanction, which could be highly specific. Asbos could be given out for swearing at others in the street, harassing passers-by, vandalism, making too much noise, graffiti, organising ‘raves’, flyposting, taking drugs, sniffing glue, joyriding, prostitution, hitting people and drinking in public.

Although they served a useful purpose in many cases, there were fears that for the really rough elements in society and their tough children they became a badge of honour. Since breaking an Asbo could result in an automatic prison sentence, people were sent to jail for crimes that had not warranted this before. But as they were refined in use and strengthened, they became more effective and routine. By 2007, seven and a half thousand had been given out in England and Wales alone and Scotland had introduced its own version in 2004. Some civil liberties campaigners saw this development as part of a wider authoritarian and surveillance agenda which also led to the widespread use of CCTV (Closed Circuit Television) cameras by the police and private security guards, especially in town centres (see above). Also in 2007, it was estimated that the British were being observed and recorded by 4.2 million such cameras. That amounted to one camera for every fourteen people, a higher ratio than for any other country in the world, with the possible exception of China. In addition, the number of mobile phones was already equivalent to the number of people in Britain. With global satellite positioning chips (GPS) these could show exactly where their users were and the use of such systems in cars and even out on the moors meant that Britons were losing their age-old prowess for map-reading.

The ‘Seven Seven’ Bombings – The Home-grown ‘Jihadis’:

Despite these increasing means of mass surveillance, Britain’s cities have remained vulnerable to terrorist attacks, more recently by so-called ‘Islamic terrorists’ rather than by the Provisional IRA, who abandoned their bombing campaign in 1998. On 7 July 2005, at rush-hour, four young Muslim men from West Yorkshire and Buckinghamshire, murdered fifty-two people and injured 770 others by blowing themselves up on London Underground trains and on a London bus. The report into this worst such attack in Britain later concluded that they were not part of an al Qaeda cell, though two of them had visited camps in Pakistan, and that the rucksack bombs had been constructed at the cost of a few hundred pounds. Despite the government’s insistence that the war in Iraq had not made Britain more of a target for terrorism, the Home Office investigation asserted that the four had been motivated, in part at least, by ‘British foreign policy’.

They had picked up the information they needed for the attack from the internet. It was a particularly grotesque attack, because of the terrifying and bloody conditions in the underground tunnels and it vividly reminded the country that it was as much a target as the United States or Spain. Indeed, the long-standing and intimate relationship between Great Britain and Pakistan, with constant and heavy air traffic between them, provoked fears that the British would prove uniquely vulnerable. Tony Blair heard of the attack at the most poignant time, just following London’s great success in winning the bid to host the 2012 Olympic Games (see above). The ‘Seven Seven’ bombings are unlikely to have been stopped by CCTV surveillance, of which there was plenty at the tube stations, nor by ID cards (which had recently been under discussion), since the killers were British subjects, nor by financial surveillance, since little money was involved and the materials were paid for in cash. Even better intelligence might have helped, but the Security Services, both ‘MI5’ and ‘MI6’ as they are known, were already in receipt of huge increases in their budgets, as they were in the process of tracking down other murderous cells. In 2005, police arrested suspects in Birmingham, High Wycombe and Walthamstow, in east London, believing there was a plot to blow up as many as ten passenger aircraft over the Atlantic.

After many years of allowing dissident clerics and activists from the Middle East asylum in London, Britain had more than its share of inflammatory and dangerous extremists, who admired al Qaeda and preached violent jihad. Once 11 September 2001 had changed the climate, new laws were introduced to allow the detention without trial of foreigners suspected of being involved in supporting or fomenting terrorism. They could not be deported because human rights legislation forbade sending back anyone to countries where they might face torture. Seventeen were picked up and held at Belmarsh high-security prison. But in December 2004, the House of Lords ruled that these detentions were discriminatory and disproportionate, and therefore illegal. Five weeks later, the Home Secretary Charles Clarke hit back with ‘control orders’ to limit the movement of men he could not prosecute or deport. These orders would also be used against home-grown terror suspects. A month later, in February 2005, sixty Labour MPs rebelled against these powers too, and the government only narrowly survived the vote. In April 2006 a judge ruled that the control orders were an affront to justice because they gave the Home Secretary, a politician, too much power. Two months later, the same judge ruled that curfew orders of eighteen hours per day on six Iraqis were a deprivation of liberty and also illegal. The new Home Secretary, John Reid, lost his appeal and had to loosen the orders.

Britain found itself in a struggle between its old laws and liberties and a new, borderless world in which the hallowed principles of ‘habeas corpus’, free speech, a presumption of innocence, asylum, the right of British subjects to travel freely in their own country without identifying papers, and the sanctity of homes in which the law-abiding lived were all coming under increasing jeopardy. The new political powers seemed to government ministers the least that they needed to deal with a threat that might last for another thirty years in order, paradoxically, to secure Britain’s liberties for the long-term beyond that. They were sure that most British people agreed, and that the judiciary, media, civil rights campaigners and elected politicians who protested were an ultra-liberal minority. Tony Blair, John Reid and Jack Straw were emphatic about this, and it was left to liberal Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats to mount the barricades in defence of civil liberties. Andrew Marr conceded at the time that the New Labour ministers were ‘probably right’. With the benefit of hindsight, others will probably agree. As Gordon Brown eyed the premiership, his rhetoric was similarly tough, but as Blair was forced to turn to the ‘war on terror’ and Iraq, he failed to concentrate enough on domestic policy. By 2005, neither of them could be bothered to disguise their mutual enmity, as pictured above. A gap seemed to open up between Blair’s enthusiasm for market ideas in the reform of health and schools, and Brown’s determination to deliver better lives for the working poor. Brown was also keen on bringing private capital into public services, but there was a difference in emphasis which both men played up. Blair claimed that the New Labour government was best when we are at our boldest. But Brown retorted that it was best when we are Labour.

Tony Blair’s legacy continued to be paraded on the streets of Britain,

here blaming him and George Bush for the rise of ‘Islamic State’ in Iraq.

Asylum Seekers, EU ‘Guest’ Workers & Immigrants:

One result of the long Iraqi conflict, which President Bush finally declared to be over on 1 May 2003, was the arrival of many Iraqi asylum-seekers in Britain; Kurds, as well as Shiites and Sunnis. This attracted little comment at the time because there had been both Iraqi and Iranian refugees in Britain since the 1970s, especially as students and the fresh influx were only a small part of a much larger migration into the country which changed it fundamentally during the Blair years. This was a multi-lingual migration, including many Poles, some Hungarians and other Eastern Europeans whose countries had joined the EU and its single market in 2004. When the EU expanded Britain decided that, unlike France or Germany, it would not try to delay opening the country to migrant workers. The accession treaties gave nationals from these countries the right to freedom of movement and settlement, and with average earnings three times higher in the UK, this was a benefit which the Eastern Europeans were keen to take advantage of. Some member states, however, exercised their right to ‘derogation’ from the treaties, whereby they would only permit migrant workers to be employed if employers were unable to find a local candidate. In terms of European Union legislation, a derogation or that a member state has opted not to enforce a specific provision in a treaty due to internal circumstances (typically a state of emergency), and to delay full implementation of the treaty for five years. The UK decided not to exercise this option.

There were also sizeable inflows of western Europeans, though these were mostly students, who (somewhat controversially) were also counted in the immigration statistics, and young professionals with multi-national companies. At the same time, there was continued immigration from Africa, the Middle East and Afghanistan, as well as from Russia, Australia, South Africa and North America. In 2005, according to the Office for National Statistics, ‘immigrants’ were arriving to live in Britain at the rate of 1,500 a day. Since Tony Blair had been in power, more than 1.3 million had arrived. By the mid-2000s, English was no longer the first language of half the primary school children in London, and the capital had more than 350 different first languages. Five years later, the same could be said of many towns in Kent and other Eastern counties of England.

The poorer of the new migrant groups were almost entirely unrepresented in politics, but radically changed the sights, sounds and scents of urban Britain, and even some of its market towns. The veiled women of the Muslim world or its more traditionalist Arab, Afghan and Pakistani quarters became common sights on the streets, from Kent to Scotland and across to South Wales. Polish tradesmen, fruit-pickers and factory workers were soon followed by shops owned by Poles or stocking Polish and East European delicacies and selling Polish newspapers and magazines. Even road signs appeared in Polish, though in Kent these were mainly put in place along trucking routes used by Polish drivers, where for many years signs had been in French and German, a recognition of the employment changes in the long-distance haulage industry. Even as far north as Cheshire (see below), these were put in place to help monolingual truckers using trunk roads, rather than local Polish residents, most of whom had enough English to understand such signs either upon arrival or shortly afterwards. Although specialist classes in English had to be laid on in schools and community centres, there was little evidence that the impact of multi-lingual migrants had a long-term impact on local children and wider communities. In fact, schools were soon reporting a positive impact in terms of their attitudes toward learning and in improving general educational standards.

Problems were posed, however, by the operations of people smugglers and criminal gangs. Chinese villagers were involved in a particular tragedy when nineteen of them were caught while cockle-picking in Morecambe Bay by the notorious tides and drowned. Many more were working for ‘gang-masters’ as virtual, in some cases actual ‘slaves’. Russian voices became common on the London Underground, and among prostitutes on the streets. The British Isles found themselves to be ‘islands in the stream’ of international migration, the chosen ‘sceptred isle’ destinations of millions of newcomers. Unlike Germany, Britain was no longer a dominant manufacturing country but had rather become, by the late twentieth century, a popular place to develop digital and financial products and services. Together with the United States and against the Soviet Union, it was determined to preserve a system of representative democracy and the free market. Within the EU, Britain maintained its earlier determination to resist the Franco-German federalist model, with its ‘social chapter’ involving ever tighter controls over international corporations and ever closer political union. Britain had always gone out into the world. Now, increasingly, the world came to Britain, whether poor immigrants, rich corporations or Chinese manufacturers.

Multilingual & Multicultural Britain:

Immigration had always been a constant factor in British life, now it was also a fact of life which Europe and the whole world had to come to terms with. Earlier post-war migrations to Britain had provoked a racialist backlash, riots, the rise of extreme right-wing organisations and a series of new laws aimed at controlling it. New laws had been passed to control both immigration from the Commonwealth and the backlash to it. The later migrations were controversial in different ways. The ‘Windrush’ arrivals from the Caribbean and those from the Indian subcontinent were people who looked different but who spoke the same language and in many ways had had a similar education to that of the ‘native’ British. Many of the later migrants from Eastern Europe looked similar to the white British but shared little by way of a common linguistic and cultural background. However, it’s not entirely true to suggest, as Andrew Marr seems to, that they did not have a shared history. Certainly, through no fault of their own, the Eastern Europeans had been cut off from their western counterparts by their absorption into the Soviet Russian Empire after the Second World War, but in the first half of the century, Poland had helped the British Empire to subdue its greatest rival, Germany, as had most of the peoples of the former Yugoslavia. Even during the Soviet ‘occupation’ of these countries, many of their citizens had found refuge in Britain.

Moreover, by the early 1990s, Britain had already become both a multilingual nation. In 1991, Safder Alladina and Viv Edwards published a book for the Longman Linguistics Library which detailed the Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish, Ukrainian and Yiddish speech communities of previous generations. Growing up in Birmingham, I certainly heard many Polish, Yiddish, Yugoslav and Greek accents among my neighbours and parents of school friends, at least as often as I heard Welsh, Irish, Caribbean, Indian and Pakistani accents. The Longman book begins with a foreword by Debi Prasanna Pattanayak in which she stated that the Language Census of 1987 had shown that there were 172 different languages spoken by children in the schools of the Inner London Education Authority. In an interesting precursor of the controversy to come, she related how the reaction in many quarters was stunned disbelief, and how one British educationalist had told her that England had become a third world country. She commented:

After believing in the supremacy of English as the universal language, it was difficult to acknowledge that the UK was now one of the greatest immigrant nations of the modern world. It was also hard to see that the current plurality is based on a continuity of heritage. … Britain is on the crossroads. It can take an isolationist stance in relation to its internal cultural environment. It can create a resilient society by trusting its citizens to be British not only in political but in cultural terms. The first road will mean severing dialogue with the many heritages which have made the country fertile. The second road would be working together with cultural harmony for the betterment of the country. Sharing and participation would ensure not only political but cultural democracy. The choice is between mediocrity and creativity.

Language and dialect in the British Isles, showing the linguistic diversity in many English cities by 1991 as a result of Commonwealth immigration as well as the survival and revival of many of the older Celtic languages and dialects of English.

Such ‘liberal’, ‘multi-cultural’ views may be unfashionable now, more than a quarter of a century later, but it is perhaps worth stopping to look back on that cultural crossroads, and on whether we are now back at that same crossroads, or have arrived at another one. By the 1990s, the multilingual setting in which new Englishes evolved had become far more diverse than it had been in the 1940s, due to immigration from the Indian subcontinent, the Caribbean, the Far East, and West and East Africa. The largest of the ‘community languages’ was Punjabi, with over half a million speakers, but there were also substantial communities of Gujurati speakers (perhaps a third of a million) and a hundred thousand Bengali speakers. In some areas, such as East London, public signs and notices recognise this (see below). Bengali-speaking children formed the most recent and largest linguistic minority within the ILEA and because the majority of them had been born in Bangladesh, they were inevitably in the greatest need of language support within the schools. A new level of linguistic and cultural diversity was introduced through Commonwealth immigration.

Birmingham’s booming postwar economy attracted West Indian settlers from Jamaica, Barbados and St Kitts in the 1950s. By 1971, the South Asian and West Indian populations were equal in size and concentrated in the inner city wards of North and Central Birmingham (see the map above). After the hostility towards New Commonwealth immigrants in some sections of the local White populations in the 1960s and ’70s, they had become more established in cities like Birmingham, where places of worship, ethnic groceries, butchers and, perhaps most significantly, ‘balti’ restaurants, began to proliferate in the 1980s and ’90s. The settlers materially changed the cultural and social life of the city, most of the ‘white’ population believing that these changes were for the better. By 1991, Pakistanis had overtaken West Indians and Indians to become the largest single ethnic minority in Birmingham. The concentration of West Indian and South Asian British people in the inner city areas changed little by the end of the century, though there was an evident flight to the suburbs by Indians. As well as being poorly-paid, the factory work available to South Asian immigrants like the man in a Bradford textile factory below, was unskilled. By the early nineties, the decline of the textile industry over the previous two decades had let to high long-term unemployment in the immigrant communities in the Northern towns, leading to serious social problems.

Nor is it entirely true to suggest that, as referred to above, Caribbean arrivals in Britain faced few linguistic obstacles integrating themselves into British life from the late 1940s to the late 1980s. By the end of these forty years, the British West Indian community had developed its own “patois”, which had a special place as a token of identity. One Jamaican schoolgirl living in London in the late eighties explained the social pressures that frowned on Jamaican English in Jamaica, but which made it almost obligatory in London. She wasn’t allowed to speak Jamaican Creole in front of her parents in Jamaica. When she arrived in Britain and went to school, she naturally tried to fit in by speaking the same patois, but some of her British Caribbean classmates told her that, as a “foreigner”, she should not try to be like them, and should speak only English. But she persevered with the patois and lost her British accent after a year and was accepted by her classmates. But for many Caribbean visitors to Britain, the patois of Brixton and Notting Hill was a stylized form that was not truly Jamaican, not least because British West Indians had come from all parts of the Caribbean. When another British West Indian girl, born in Britain, was taken to visit Jamaica, she found herself being teased about her London patois and told to speak English.

The predicament that still faced the ‘Black British’ in the late eighties and into the nineties was that, for all the rhetoric, they were still not fully accepted by the established ‘White community’. Racism was still an everyday reality for large numbers of British people. There was plenty of evidence of the ways in which Black people were systematically denied access to employment in all sections of the job market. The fact that a racist calamity like the murder in London of the black teenager Stephen Lawrence could happen in 1993 was a testimony to how little had changed in British society’s inability to face up to racism since the 1950s. As a result, the British-Caribbean population could still not feel itself to be neither fully British. This was the poignant outcome of what the British Black writer Caryl Phillips has called “The Final Passage”, the title of his novel which is narrated in Standard English with the direct speech by the characters rendered in Creole. Phillips migrated to Britain as a baby with his parents in the 1950s, and sums up his linguistic and cultural experience as follows:

“The paradox of my situation is that where most immigrants have to learn a new language, Caribbean immigrants have to learn a new form of the same language. It induces linguistic shizophrenia – you have an identity that mirrors the larger cultural confusion.”

One of his older characters in The Final Passage characterises “England” as a “college for the West Indian”, and, as Philipps himself put it, that is “symptomatic of the colonial situation; the language is divided as well”. As the “Windrush Scandal”, involving the deportation of British West Indians from the UK has recently shown, this post-colonial “cultural confusion” still ‘colours’ political and institutional attitudes twenty-five years after the death of Stephen Lawrence, leading to discriminatory judgements by officials. This example shows how difficult it is to arrive at some kind of chronological classification of migrations to Britain into the period of economic expansion of the 1950s and 1960s; the asylum-seekers of the 1970s and 1980s; and the EU expansion and integration in the 1990s and the first decades of the 2000s. This approach assumed stereotypical patterns of settlement for the different groups, whereas the reality was much more diverse. Most South Asians, for example, arrived in Britain in the post-war period but they were joining a migration ‘chain’ which had been established at the beginning of the twentieth century. Similarly, most Eastern European migrants arrived in Britain in several quite distinct waves of population movement. This led the authors of the Longman Linguistics book to organise it into geolinguistic areas, as shown in the figure below:

The Poles and Ukrainians of the immediate post-war period, the Hungarians in the 1950s, the Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s and the Tamils in the 1980s, sought asylum in Britain as refugees. In contrast, settlers from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the Caribbean, had, in the main come from areas of high unemployment and/or low wages, for economic reasons. It was not possible, even then, to make a simple split between political and economic migrants since, even within the same group, motivations differed through time. The Eastern Europeans who had arrived in Britain since the Second World War had come for a variety of reasons; in many cases, they were joining earlier settlers trying either to escape poverty in the home country or to better their lot. A further important factor in the discussion about the various minority communities in Britain was the pattern of settlement. Some groups were concentrated into a relatively small geographical area which made it possible to develop and maintain strong social networks; others were more dispersed and so found it more difficult to maintain a sense of community. Most Spaniards, Turks and Greeks were found in London, whereas Ukrainians and Poles were scattered throughout the country. In the case of the Poles, the communities outside London were sufficiently large to be able to sustain an active community life; in the case of Ukrainians, however, the small numbers and the dispersed nature of the community made the task of forging a separate linguistic and cultural identity a great deal more difficult.

Groups who had little contact with the home country also faced very real difficulties in retaining their distinct identities. Until 1992, Lithuanians, Latvians, Ukrainians and Estonians were unable to travel freely to their country of origin; neither could they receive visits from family members left behind; until the mid-noughties, there was no possibility of new immigration which would have the effect of revitalizing these communities in Britain. Nonetheless, they showed great resilience in maintaining their ethnic minority, not only through community involvement in the UK but by building links with similar groups in Europe and even in North America. The inevitable consequence of settlement in Britain was a shift from the mother tongue to English. The extent of this shift varied according to individual factors such as the degree of identification with the mother tongue culture; it also depended on group factors such as the size of the community, its degree of self-organisation and the length of time it had been established in Britain. For more recently arrived communities such as the Bangladeshis, the acquisition of English was clearly a more urgent priority than the maintenance of the mother tongue, whereas, for the settled Eastern Europeans, the shift to English was so complete that mother tongue teaching was often a more urgent community priority. There were reports of British-born Ukrainians and Yiddish-speaking Jews who were brought up in predominantly English-speaking homes who were striving to produce an environment in which their children could acquire their ‘heritage’ language.

Blair’s Open Door Policy & EU Freedom of Movement:

During the 1980s and ’90s, under the ‘rubric’ of multiculturalism, a steady stream of immigration into Britain continued, especially from the Indian subcontinent. But an unspoken consensus existed whereby immigration, while always gradually increasing, was controlled. What happened after the Labour Party’s landslide victory in 1997 was a breaking of that consensus, according to Douglas Murray, the author of the recent (2017) book, The Strange Death of Europe. He argues that once in power, Tony Blair’s government oversaw an opening of the borders on a scale unparalleled even in the post-war decades. His government abolished the ‘primary purpose rule’, which had been used as a filter out bogus marriage applications. The borders were opened to anyone deemed essential to the British economy, a definition so broad that it included restaurant workers as ‘skilled labourers’. And as well as opening the door to the rest of the world, they opened the door to the new EU member states after 2004. It was the effects of all of this, and more, that created the picture of the country which was eventually revealed in the 2011 Census, published at the end of 2012.

The numbers of non-EU nationals moving to settle in Britain were expected only to increase from 100,000 a year in 1997 to 170,000 in 2004. In fact, the government’s predictions for the number of new arrivals over the five years 1999-2004 were out by almost a million people. It also failed to anticipate that the UK might also be an attractive destination for people with significantly lower average income levels or without a minimum wage. For these reasons, the number of Eastern European migrants living in Britain rose from 170,000 in 2004 to 1.24 million in 2013. Whether the surge in migration went unnoticed or was officially approved, successive governments did not attempt to restrict it until after the 2015 election, by which time it was too late.

(to be continued)

Posted January 15, 2019 by AngloMagyarMedia in Affluence, Africa, Arabs, Assimilation, asylum seekers, Belfast, Birmingham, Black Market, Britain, British history, Britons, Bulgaria, Calais, Caribbean, Celtic, Celts, Child Welfare, Cold War, Colonisation, Commonwealth, Communism, Compromise, Conservative Party, decolonisation, democracy, Demography, Discourse Analysis, Domesticity, Economics, Education, Empire, English Language, Europe, European Economic Community, European Union, Factories, History, Home Counties, Humanism, Humanitarianism, Hungary, Immigration, Imperialism, India, Integration, Iraq, Ireland, Journalism, Labour Party, liberal democracy, liberalism, Linguistics, manufacturing, Margaret Thatcher, Midlands, Migration, Militancy, multiculturalism, multilingualism, Music, Mythology, Narrative, National Health Service (NHS), New Labour, Old English, Population, Poverty, privatization, Racism, Refugees, Respectability, Scotland, Socialist, south Wales, terror, terrorism, Thatcherism, Unemployment, United Kingdom, United Nations, Victorian, Wales, Welsh language, xenophobia, Yugoslavia

Tagged with 'Middle Englanders', al Qaeda, Alan Milburn, Albert Dock, Amazon, Amsterdam, Andrew Marr, Aneurin Bevan, Anti-Social Behaviour Order ('Asbo'), Bangladesh, Bengali, Blair-Brown government, Bradford, Brixton, broadband, Bupa, Business, Caribbean, Caryl Philipps, CCTV, Charles Clarke, Cheshire, Child Poverty Action Group, Chinese, civil liberties, Creole, culture, current-events, derogation, diversity, Douglas Murray, downloading, eBay, Education, England, Ethnic minorities, EU, European Community, federalism, France, Freedom of Movement, GDP, Germany, Gordon Brown, Gujurati, habeas corpus, History, Iraq, Ireland, Islam, Jack Straw, Jamaica, Jihad, John Reid, Kurds, Liverpool, Maastricht Treaty, Michael Howard, minimum wage, Morecambe Bay, New Deal, Notting Hill, Office of National Statistics (ONS), Olympic Games 2012, Open Door Policy, Pakistan, patois, Poland, politics, Polly Toynbee, Punjabi, Queen Elizabeth II, Railtrack, redistribution of wealth, referendum, Robert Winston, Royal College of Nursing, security services, society, South Asian, Spice Girls, Sure Start, surveillance, The Final Passage, the Guardian, third world, Tim Berners-Lee, Tony Blair, Treasury, UN, Victorian values, Wanless Report, West Indian, Westminster, Whitehall, Windrush, working families' tax credit

Keith Joseph, Margaret Thatcher’s main supporter in her election as Conservative leader and in her early governments, once said that, in the past, Britain’s trouble had been that she had never had a proper capitalist ruling class. In 1979, the first Thatcher government sought consciously to put this right. The task it set itself was daunting – the liberation of British enterprise from a hundred years of reactionary accretions, in order to return the machine to the point along the path where it had stood when it was diverted away. It was helped by the fact that, with the empire gone, very little remained to sustain the older, obstructive, pre-capitalist values any longer, or to cushion Britain against the retribution her industrial shortcomings deserved. This movement promised to mark the real and final end of empire, the Thatcher government’s determination to restore the status quo ante imperium, which meant, in effect, before the 1880s, when imperialism had started to take such a hold on Britain. Thatcher looked back to the Victorian values of Benjamin Disraeli’s day, if not to those of William Gladstone. She itemized these values in January 1983 as honesty, thrift, reliability, hard work and a sense of responsibility. This list strikingly omitted most of the imperial values, like service, loyalty and fair play, though she did, later on, add ‘patriotism’ to them. Nevertheless, the new patriotism of the early 1980s was very different from that of the 1880s, even when it was expressed in a way which seemed to have a ring of Victorian imperialism about it.

Part of the backdrop to the Falklands War was the residual fear of global nuclear war. With hindsight, the Soviet Union of Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko may seem to be a rusted giant, clanking helplessly towards a collapse, but this is not how it seemed prior to 1984. The various phases of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START) were underway, but to well-informed and intelligent analysts the Soviet empire still seemed mighty, belligerent and unpredictable. New SS20 missiles were being deployed by the Soviets, targeted at cities and military bases across western Europe. In response, NATO was planning a new generation of American Pershing and Cruise missiles to be sited in Europe, including in Britain. In the late winter of 1979 Soviet troops had begun arriving in Afghanistan, Mikhail Gorbachev was an obscure member of the Politburo working on agricultural planning, and glasnost was a word no one in the West had heard of. Poland’s free trade union movement, Solidarity, was being crushed by a military dictator. Following the invasion of Afghanistan, President Carter had issued an ultimatum: the Soviets must withdraw or the United States would boycott the Moscow Olympic Games due to be held in the summer of 1980. Margaret Thatcher supported the call for a boycott, but the British Olympic Association showed its independence from government and defiantly sent a team, supported by voluntary contributions from students, among others. Two British middle-distance runners, Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett each won gold medals.

Western politics echoed with arguments over weapons systems, disarmament strategies and the need to stand up to the Soviet threat. Moscow had early and rightly identified Margaret Thatcher as one of its most implacable enemies. She had already been British Prime Minister for eighteen months when Ronald Reagan’s administration took over in Washington. He may have been many things Thatcher was not, but like her, he saw the world in black and white terms, especially in his first term to 1984. She was from a Methodist background, he was from a Presbyterian one, so they both shared a view of the world as a great stage on which good and evil, God and Satan, were pitched against each other in endless conflict. Reagan found a ‘soul mate’ in Thatcher. Already dubbed the ‘Iron Lady’ by the Russians, Thatcher was resolute in her determination to deregulate government and allow the benefits of capitalism to flourish at home and abroad. Although the UK was committed to Europe, Thatcher was also a strong believer in Britain’s “enduring alliance” with the United States. Reagan and Thatcher saw eye-to-eye on many key issues. Their shared detestation of socialism in general and Soviet communism, in particular, underpinned their remarkably close personal relationship which was eventually to help steer the world away from Armageddon.

Of course, in a sense, the Falklands War of 1982 could be seen as an imperial war, fought as it was over a fag-end of Britain’s old empire: but that was an accident. There was no imperial rationale for the war. Britain did not fight the Argentines for profit, for potential South Atlantic oil reserves (as some suggested), or for the security of her sea lanes, or indeed for the material or spiritual good of anyone. She fought them for a principle, to resist aggression and to restore her government’s sovereignty over the islands in the interests of the islanders themselves. The war also served to restore to Britain some of the national pride which many commentators had long suggested was one of the other casualties of the empire’s demise. That was what made an otherwise highly burdensome operation worthwhile if that sense of pride could be translated into what Sir Nicolas Henderson had described three years earlier as a sense of national will. Similarly, Margaret Thatcher believed that if British Leyland could be injected with some of the same ‘Falklands spirit’ then there was no reason why British industry could not reverse its decline. The popular jingoism the affair aroused and encouraged showed that a post-imperial Britain would not necessarily be a post-militaristic one. But it was not an imperial jingoism per se, more one which expressed a national pride and patriotism. It did not indicate in the least that ‘imperialism’ proper was about to be resurrected, even if that were practicable; or that anyone intended that it should be.

However proud Britons were to have defended the Falklands, no one was particularly proud any longer of having them to defend. Most of Britain’s remaining colonial responsibilities were regarded now as burdens it would much rather be without and would have been if it could have got away with scuttling them without loss of honour or face. In her new straitened circumstances, they stretched its defence resources severely, and to the detriment of its main defence commitment, to NATO. They also no longer reflected Britain’s position in the world. When Hong Kong and the Falklands had originally been acquired, they had been integral parts of a larger pattern of commercial penetration and naval ascendancy. They had been key pieces in a jigsaw, making sense in relation to the pieces around them. Now those pieces had gone and most of the surviving ones made little sense in isolation, or they made a different kind of sense from before. If the Falklands was an example of the former, Hong Kong was a good example of the latter, acting as it now did as a kind of ‘cat-flap’ into communist China. The Falklands was the best example of an overseas commitment which, partly because it never had very much value to Britain, now had none at all.

Diplomatically, the Falklands ‘Crisis’ as it was originally known, was an accident waiting to happen, no less embarrassing for that. At the time, the defence of western Europe and meeting any Soviet threat was the main concern, until that began to abate from 1984 onwards. The British Army was also increasingly involved in counter-insurgency operations in Northern Ireland. Small military detachments helped to guard remaining outposts of the empire such as Belize. But Argentine claims to the Falklands were not taken seriously, and naval vessels were withdrawn from the South Atlantic in 1981. In April 1982, though, Argentina launched a surprise attack on South Georgia and the Falklands and occupied the islands.

Even if oil had been found off its shores, or South Georgia could have been used as a base from which to exploit Antarctica, Britain was no longer the sort of power which could afford to sustain these kinds of operations at a distance of eight thousand miles. The almost ludicrous measures that had to be put into place in order to supply the Falklands after May 1982 illustrate this: with Ascension Island serving as a mid-way base, and Hercules transport aircraft having to be refuelled twice in the air between there and Port Stanley, in very difficult manoeuvres. All this cost millions, and because Britain could not depend on the South American mainland for more convenient facilities.

Even if oil had been found off its shores, or South Georgia could have been used as a base from which to exploit Antarctica, Britain was no longer the sort of power which could afford to sustain these kinds of operations at a distance of eight thousand miles. The almost ludicrous measures that had to be put into place in order to supply the Falklands after May 1982 illustrate this: with Ascension Island serving as a mid-way base, and Hercules transport aircraft having to be refuelled twice in the air between there and Port Stanley, in very difficult manoeuvres. All this cost millions, and because Britain could not depend on the South American mainland for more convenient facilities.

But it was not only a question of power. Britain’s material interests had contracted too: especially her commercial ones. For four centuries, Britain’s external trade had used to have a number of distinctive features, two of which were that it far exceeded any other country’s foreign trade and that most of it was carried on outside Europe. However, between 1960 and 1980, Britain’s pattern of trade had shifted enormously, towards Europe and away from the ‘wider world’. In 1960, less than thirty-two per cent of Britain’s exports went to western Europe and thirty-one per cent of imports came from there; by 1980, this figure had rocketed to fifty-seven per cent of exports and fifty-six per cent of imports. In other words, the proportion of Britain’s trade with Europe grew by twenty-five per cent, compared to its trade with the rest of the world. Of course, this ‘shift’ was partly the result of a political ‘shift’ in Britain to follow a more Eurocentric commercial pattern, culminating in the 1975 Referendum on EEC membership.

By 1980 Britain was no longer a worldwide trading nation to anything like the extent it had been before. Moreover, in 1983, a symbolic turning-point was reached when, for the first time in more than two centuries, Britain began importing more manufactured goods than it exported. It followed that it was inappropriate for it still to have substantial political responsibilities outside its own particular corner of the globe. British imperialism, therefore, was totally and irrevocably finished, except as a myth on the right and the left. I remember Channel Four in the UK screening a programme called ‘the Butcher’s Apron’ in 1983 which argued, from a left-wing perspective, that it was still very much alive, and that the Falklands War was clear evidence of this. Likewise, there were, and still are, many nationalists in Scotland and Wales who used the term as a metaphor for the ‘domination’ of England and ‘the British state’ over their countries. Of course, in historical terms, they could only do this because the British Empire was a thing of the past, and the sending of Welsh guardsmen to recover islands in the South Atlantic was an unintended and embarrassing postscript, never to be repeated.

The imperial spirit had dissipated too, despite Mrs Thatcher’s brief attempt to revive it in Falklands jingoism and whatever might be said by supercilious foreign commentators who could not credit the British for having put their imperialist past behind them so soon after Suez and all that and certainly by 1970, when they had abandoned overseas defence commitments ‘east of Suez’. But Britain had indeed left its past behind it, even to the extent of sometimes rather rudely ‘putting its behind in its past’ to emphasise the point. Scattered around the globe were a few little boulders, ‘survivals’ from the imperial past, which were no longer valued by Britain or valuable to her. There were also some unresolved problems, such as Rhodesia, which became Zimbabwe, as an independent territory in 1980. Britain had clearly dissociated itself from its white racist leaders even at the cost of bringing an ‘unreconstructed Marxist’ to power. After that, smaller island colonies in the Caribbean and the Pacific continued to be granted their independence, so that by 1983 the Empire had effectively ceased to exist.

In 1984 Bernard Porter wrote, in the second edition of his book on British imperialism, that it was…

… unlikely that any subsequent edition of this book, if the call for it has not dried up completely, will need to go beyond 1980, because British imperialism itself is unlikely to have a life beyond then. That chapter of history is now at an end.

It was not a very long chapter, as these things go; but it is difficult to see how it could have been. The magnificent show that the British empire made at its apogee should not blind us to its considerable weaknesses all through. Those who believe that qualities like ‘will’ and ‘leadership’ can mould events might not accept this, of course; but there was nothing that anyone could have done in the twentieth century to stave off the empire’s decline. It was just too riddled with contradictions.

The Imperialists themselves were the first to predict the decline; that Britain could not help but be overhauled and overshadowed by the growing Russian and American giants. Britain did not have the will to resist this development and the empire was not, in any case, a fit tool for resistance. While Britain had it, in fact, the Empire was rarely a source of strength to the ‘mother country’, despite the attempts of imperialists to make it so.

A part of the narrative of the Falklands Crisis not revealed at the time was the deep involvement, and embarrassment, of the United States. Mrs Thatcher and President Reagan had already begun to develop their personal special relationship. But the Argentine junta was important to the US for its anti-Communist stance and as a trading partner. Prior to 1982, the United States had supported the Argentine generals, despite their cruel record on human rights, partly because of the support they gave the ‘Contras’ in Nicaragua. Therefore, they began a desperate search for a compromise while Britain began an equally frantic search for allies at the United Nations. In the end, Britain depended on the Americans not just for the Sidewinder missiles underneath its Harrier jets, without which Thatcher herself said the Falklands could not have been retaken, but for intelligence help and – most of the time – diplomatic support too. These were the last years of the Cold War. Britain mattered more in Washington than any South American country. Still, many attempts were made the US intermediary, the Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, to find a compromise. They would continue throughout the fighting. Far more of Thatcher’s time was spent reading, analysing and batting off possible deals than contemplating the military plans. Among those advising a settlement was the new Foreign Secretary, Francis Pym, appointed after Lord Carrington’s resignation. Pym and the Prime Minister were at loggerheads over this and she would punish him in due course. She had furious conversations with Reagan by phone as he tried to persuade her that some outcome short of British sovereignty, probably involving the US, was acceptable.

Thatcher broke down the diplomatic deal-making into undiplomatic irreducibles. Would the Falkland Islanders be allowed full self-determination? Would the Argentine aggression be rewarded? Under pulverizing pressure she refused to budge. She wrote to Ronald Reagan, who had described the Falklands as that little ice-cold bunch of land down there, that if Britain gave way to the various Argentine snares, the fundamental principles for which the free world stands would be shattered. Reagan kept trying, Pym pressed and the Russians harangued, all to no avail. Despite all the logistical problems, a naval task force set sail, and with US intelligence support, the islands were regained after some fierce fighting.

Back in London in the spring of 1984, Margaret Thatcher’s advisers looked into the new, younger members of the Soviet Politburo who had emerged under Konstantin Chernenko, the last of the ‘old guard’. He was old and frail, like his predecessor, Yuri Andropov. The advisors to the Prime Minister wondered with whom she, and they, would be dealing with next, and issued a number of invitations to visit Britain. By chance, the first to accept was Mikhail Gorbachev, who visited Thatcher in London. He arrived with his wife, Raisa, itself remarkable, as Soviet leaders rarely travelled with their wives. By comparison to the old men who had led the Soviet Union for twenty years, the Gorbachevs were young, lively and glamorous. The visit was a great success. After Thatcher and Gorbachev met, the Prime Minister was asked by reporters what she thought of her guest. She replied with a statement that, again with the benefit of hindsight, was to usher in the final stage of the Cold War:

Sources:

David Killingray (2001), The Penguin Atlas of British & Irish History. London: Penguin Books.

Bernard Porter (1984), A Short History of British Imperialism, 1850-1983. Harlow: Longman.

Andrew Marr (2008), A History of Modern Britain. Basingstoke: Macmillan Pan.

Demographics and Reconfigurations:

The 1960s were dramatic years in Britain: demographic trends, especially the increase in the proportion of teenagers in the population, coincided with economic affluence and ideological experimentation to reconfigure social mores to a revolutionary extent. In 1964, under Harold Wilson, the Labour Party came into power, promising economic and social modernisation. In an attempt to tackle the problem of poverty, public expenditure on social services was expanded considerably, resulting in a small degree of redistribution of income. Economically, the main problems of the decade arose from the devaluation of the currency in 1967 and the increase in industrial action. This was the result of deeper issues in the economy, such as the decline of the manufacturing industry to less than one-third of the workforce. In contrast, employment in the service sector rose to over half of all workers. Young people were most affected by the changes of the 1960s. Education gained new prominence in government circles and student numbers soared. By 1966, seven new universities had opened (Sussex, East Anglia, Warwick, Essex, York, Lancaster and Kent). More importantly, students throughout the country were becoming increasingly radicalized as a response to a growing hostility towards what they perceived as the political and social complacency of the older generation. They staged protests on a range of issues, from dictatorial university decision-making to apartheid in South Africa, and the continuance of the Vietnam War.

Above: A Quaker ‘advertisement’ in the Times, February 1968.

Vietnam, Grosvenor Square and All That…

The latter conflict not only angered the young of Britain but also placed immense strain on relations between the US and British governments. Although the protests against the Vietnam War were less violent than those in the United States, partly because of more moderate policing in Britain, there were major demonstrations all over the country; the one which took place in London’s Grosvenor Square, home to the US Embassy, in 1968, involved a hundred thousand protesters. Like the world of pop, ‘protest’ was essentially an American import. When counter-cultural poets put on an evening of readings at the Albert Hall in 1965, alongside a British contingent which included Adrian Mitchell and Christopher Logue, the ‘show’ was dominated by the Greenwich Village guru, Allen Ginsberg. It was perhaps not surprising that the American influence was strongest in the anti-war movement. When the Vietnam Solidarity Committee organised three demonstrations outside the US embassy in London’s Grosvenor Square, the second of them particularly violent, they were copying the cause and the tactics used to much greater effect in the United States. The student sit-ins and occupations at Hornsey and Guildford Art Colleges and Warwick University were pale imitations of the serious unrest on US and French campuses. Hundreds of British students went over to Paris to join what they hoped would be a revolution in 1968, until de Gaulle, with the backing of an election victory, crushed it. This was on a scale like nothing seen in Britain, with nearly six hundred students arrested in fights with the police on a single day and ten million workers on strike across France.

Wilson & the ‘White Heat’ of Technological Revolution:

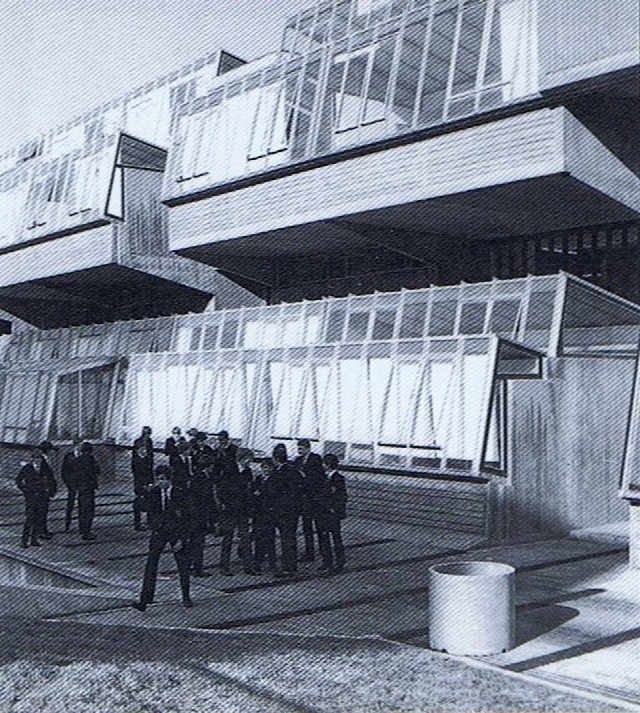

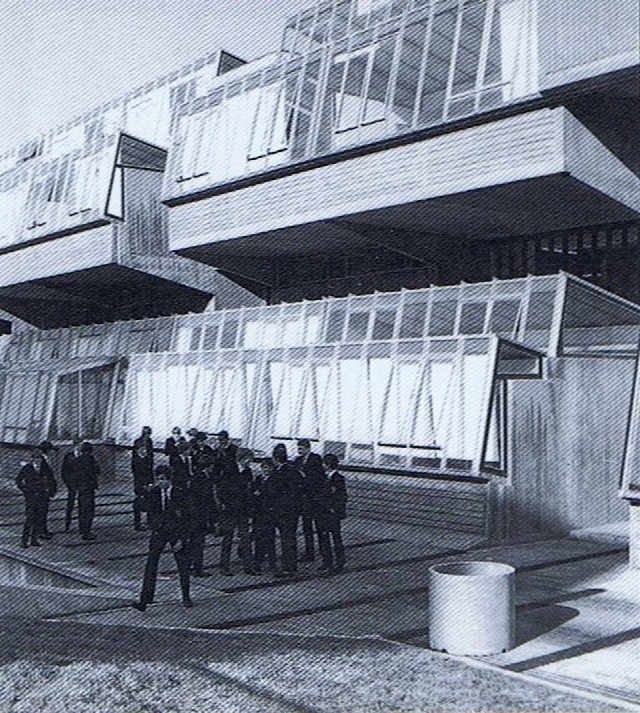

Andrew Marr has commented that the term ‘Modern Britain’ does not simply refer to the look and shape of the country – the motorways and mass car economy, the concrete, sometimes ‘brutalist’ architecture, the rock music and the high street chains. It also refers to the widespread belief in planning and management. It was a time of practical men, educated in grammar schools, sure of their intelligence. They rolled up their sleeves and took no-nonsense. They were determined to scrap the old and the fusty, whether that meant the huge Victorian railway network, the Edwardian, old Etonian establishment in Whitehall, terraced housing, censorship, prohibitions on homosexual behaviour and abortion. The country seemed to be suddenly full of bright men and women from lower-middle-class or upper-working-class families who were rising fast through business, universities and the professions who were inspired by Harold Wilson’s talk of a scientific and technological revolution that would transform Britain. In his speech to Labour’s 1963 conference, the most famous he ever made, Wilson pointed out that such a revolution would require wholesale social change:

The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods … those charged with the control of our affairs must be ready to think and speak in the language of our scientific age. … the formidable Soviet challenge in the education of scientists and technologists in Soviet industry (necessitates that) … we must use all the resources of democratic planning, all the latent and underdeveloped energies and skills of our people to ensure Britain’s standing in the world.

In some ways, however, this new Wilsonian Britain was already out of date by the mid-sixties. In any case, his vision, though sounding ‘modern’ was essentially that of an old-fashioned civil servant. By 1965, Britain was already becoming a more feminised, sexualized, rebellious and consumer-based society. The political classes were cut off from much of this cultural undercurrent by their age and consequent social conservatism. They looked and sounded what they were, people from a more formal time, typified by the shadow cabinet minister, Enoch Powell MP.

Education – The Binary Divide & Comprehensivisation: