Archive for the ‘Churchill’ Tag

Above: NAZI GERMANY & ITS ALLIED/ OCCUPIED TERRITORIES IN 1945

The Aftermath of the Ardennes Offensive:

The German army’s losses in 1944 were immense, adding up to the equivalent of more than a hundred divisions. Nevertheless, during this period Hitler managed to scrape up a reserve of twenty-five divisions which he committed in December to a re-run of his 1940 triumph in France, an offensive in the Ardennes, the so-called Battle of the Bulge. For a few days, as the panzers raced towards the Meuse, the world wondered if Hitler had managed to bring it off. But the Allies had superior numbers and the tide of battle soon turned against the Germans, who were repulsed within three weeks, laying Germany open for the final assault from the West. For this, the Allies had eighty-five divisions, twenty-three of which were armoured, against a defending force of twenty-six divisions. Rundstedt declared after the war:

I strongly object to the fact that this stupid operation in the Ardennes is sometimes called the “Rundstedt Offensive”. This is a complete misnomer. I had nothing to do with it. It came to me as an order complete to the last detail. Hitler had even written “Not to be Altered”.

In the Allied camp, Montgomery told a press conference at his Zonhoven headquarters on 7 January that he saluted the brave fighting men of America:

… I never want to fight alongside better soldiers. … I have tried to feel I am almost an American soldier myself so that I might take no unsuitable action to offend them in any way.

However, his sin of omission in not referring to any of his fellow generals did offend them and further inflamed tensions among the Anglo-American High Command. Patton and Montgomery loathed each other anyway, the former calling the latter that cocky little limey fart, while ‘Monty’ thought the American general a foul-mouthed lover of war. As the US overhauled Britain in almost every aspect of the war effort, Montgomery found himself unable to face being eclipsed and became progressively more anti-American as the stars of the States continued to rise. So when censorship restrictions were lifted on 7 January, Montgomery gave his extensive press briefing to a select group of war correspondents. His ineptitude shocked even his own private staff, and some believed he was being deliberately offensive, especially when he boasted:

General Eisenhower placed me in command of the whole northern front. … I employed the whole available power of the British group of armies. You have this picture of British troops fighting on both sides of American forces who had suffered a hard blow. This is a fine Allied picture.

Although he spoke of the average GIs as being ‘jolly brave’ in what he called ‘an interesting little battle’, he claimed he had entered the engagement ‘with a bang’, and left the impression that he had effectively rescued the American generals from defeat. Bradley then described Montgomery to Eisenhower as being all out, right-down-to-the-toes-mad, telling ‘Ike’ that he could not serve with him, preferring to be sent home to the US. Patton immediately made the same declaration. Then Bradley started holding court to the press himself and, together with Patton, leaked damaging information about Montgomery to American journalists. Montgomery certainly ought to have paid full tribute to Patton’s achievement in staving off the southern flank of the Ardennes offensive, but the US general was not an attractive man to have as a colleague. He was a white supremacist and an anti-Semite, and his belief in the Bolshevik-Zionist conspiracy remained unaffected by the liberation of the concentration camps which was soon to follow. Whatever the reasons for Montgomery’s dislike of Patton, as Andrew Roberts has pointed out:

The British and American generals in the west from 1943 to 1945 did indeed have a special relationship: it was especially dreadful.

Despite their quarrelling, by 16 January, the Allies had resumed their advance as the British, Americans and French gradually forced their way towards the Rhine. The German order to retreat was finally given on 22nd, and by 28th there was no longer a bulge in the Allied line, but instead, a large one developing in that of the Germans.

The Oder-Vistula Offensive & Hitler’s ‘Bunker’ Mentality:

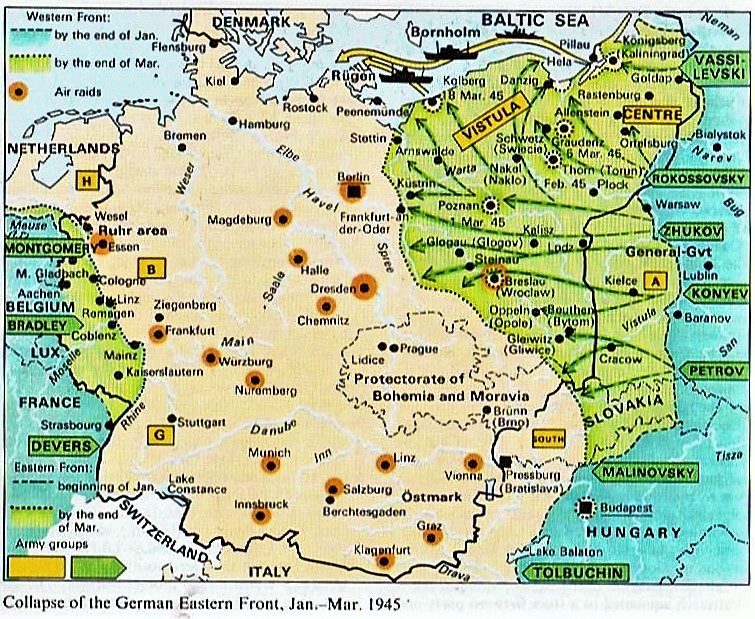

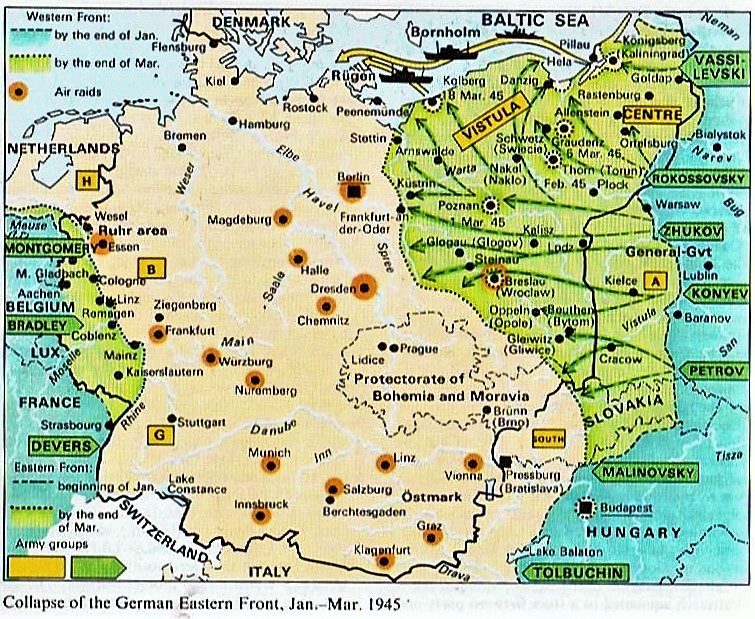

Meanwhile, the Red Army had burst across the Vistula and then began clearing Pomerania and Silesia. The 12th January had seen the beginning of a major Soviet offensive along the entire front from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Carpathian mountains in the south, against what was left of the new German Central front, made up of the seventy divisions of Army Group Centre and Army Group A. The Red Army first attacked from the Baranov bridgehead, demolishing the German Front of the Centre sector. Planned by Stalin and the ‘Stavka’, but expertly implemented by Zhukov, this giant offensive primarily comprised, from the south to the north, as shown on the map above: Konyev’s 1st Ukrainian, Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian, Rokossovsky’s 2nd Belorussian, Chernyakovsky’s 3rd Belorussian, Bagryan’s 1st Baltic and Yeremenko’s 2nd Baltic Fronts, so no fewer than two hundred divisions in all.

Faced with this onslaught, wildly outnumbered and outgunned, the Germans conducted an impressive fighting retreat of almost three hundred miles, losing Warsaw on 17 January and leaving isolated garrisons at Thorn, Poznan and Breslau that had no real hope of relief. The Polish territories which remained under occupation were lost, as was Upper Silesia with its undamaged industrial area and Lower Silesia east of the Oder. Almost one million German citizens were sheltering in or around the city of Breslau in Lower Silesia, which was not a fortress in the conventional sense despite attempts following August 1944 to build a defensive ring at a ten-mile radius from the city centre. On 20 and 21 January, Women and children were told through loudspeakers to leave the city on foot and proceed in the direction of Opperau and Kanth. This effectively expelled them into three-foot snowdrifts and temperatures of -20 Celsius. The babies were usually the first to die, the historian of Breslau’s subsequent seventy-seven-day siege recorded. Ammunition and supplies were parachuted in by the Luftwaffe, but these often fell into the Oder or behind the Russian lines. The city did not surrender until 6 May and its siege cost the lives of 28,600 of its 130,000 soldiers and civilians.

During the first two months of 1945, Hitler was living in a world of self-delusion, while continuing to direct operations from his bomb-proof bunker deep beneath the Chancellory in Berlin. His orders were always the same: stand fast, hold on, shoot any waverers and sell your own lives as dearly as possible. It’s impossible to tell, even from the verbatim reports of Hitler’s briefings of the Reich’s most senior figures, when exactly he realised that he was bound to lose the war, and with it his own life. It possibly came at the end of the ‘Battle of the Bulge’ at the close of 1944, or in the first week of 1945, for on 10 January he had the following conversation with Göring over the problems with the production of secret weaponry:

HITLER: It is said that if Hannibal, instead of the seven or thirteen elephants he had left as he crossed the Alps … had had fifty or 250, it would have been more than enough to conquer Italy.

GÖRING: But we did finally bring out the jets; we brought them out. And they most come in masses, so we keep the advantage.

HITLER: The V-1 can’t decide the war, unfortunately.

GÖRING: … Just as an initially unpromising project can finally succeed, the bomber will come too, if it is also –

HITLER: But that’s still just a fantasy!

GÖRING: No!

HITLER: Göring, the gun is there, the other is still a fantasy!

Although there were often up to twenty-five people in the room during these Führer-conferences, Hitler usually had only two or three interlocutors. It was after one such conference in February that Albert Speer tried to explain to Admiral Dönitz how the war was certainly lost, with the maps there showing a catastrophic picture of innumerable breakthroughs and encirclements, but Dönitz merely replied with an unwonted curtness that he was only there to represent the Navy and that the rest was none of his business. The Führer must know what he is doing, he added. Speer believed that if Dönitz, Göring, Keitel, Jodl, Guderian and himself had presented the Führer with an ultimatum, and demanded to know his plans for ending the war, then Hitler would have had to have declared himself. Yet that was never going to happen, because they suspected, not without justification as it turned out, that by then there was soon only to be a rope at the end of it. When Speer approached Göring at Karinhall soon after he had spoken to Dönitz, the Reichsmarschall readily admitted that the Reich was doomed, but said that he had:

… much closer ties with Hitler; many years of common experiences and struggles had bound them together – and he could no longer break loose.

By the end of January, the military situation both in the west and the east was already quite beyond Hitler’s control: the Rhine front collapsed as soon as the Allies challenged it, and leaving the last German army in west locked up in the Ruhr, the British and Americans swept forward to the Elbe. Hitler’s dispositions continued to make Germany’s strategic situation worse. Guderian recalled after the war that the Führer had refused his advice to bring the bulk of the ‘Wehrmacht’ stationed in Poland back from the front line to more defensible positions twelve miles further back, out of range of Russian artillery. Disastrously, Hitler’s orders meant that the new defensive line, only two miles behind the front, were badly hit by the Soviet guns, wrecking any hopes for a classic German counter-attack. A historian of the campaign has remarked that this was an absolute contradiction of German military doctrine. Hitler’s insistence on personally authorising everything done by his Staff was explained to Guderian with hubristic words:

There’s no need for you to try and teach me. I’ve been commanding the Wehrmacht in the field for five years and during that time I’ve had more practical experience than any gentlemen of the General Staff could ever hope to have. I’ve studied Clausewitz and Moltke and read all the Schlieffen papers. I’m more in the picture than you are!

A few days into the great Soviet offensive in the east, Guderian challenged Hitler aggressively over his refusal to evacuate the German army in Kurland, which had been completely cut off against the Baltic. When Hitler refused the evacuation across the Baltic, as he always did when asked to authorise a retreat, according to Speer, Guderian lost his temper and addressed his Führer with an openness unprecedented in this circle. He stood facing Hitler across the table in the Führer’s massive office in the Reich Chancellery, with flashing eyes and the hairs of his moustache literally standing on end saying, in a challenging voice: “It’s simply our duty to save these people, and we still have time to remove them!”Hitler stood up to answer back: “You are going to fight on there. We cannot give up those areas!” Guderian continued, “But it’s useless to sacrifice men in this senseless way. It’s high time! We must evacuate these soldiers at once!” According to Speer, although he got his way, …

… Hitler appeared visibly intimidated by this assault … The novelty was almost palpable. New worlds had opened out.

As the momentum of the Red Army’s Oder-Vistula offensive led to the fall of Warsaw later that month, three senior members of Guderian’s planning staff were arrested by the Gestapo and questioned about their apparent questioning of orders from the OKW. Only after Guderian spent hours intervening on their behalf were two of them released, though the third was sent to a concentration camp. The basis of the problem not only lay in the vengeful Führer but in the system of unquestioning obedience to orders which had been created around him, which was in fundamental conflict with the General Staff’s system of mutual trust and exchange of ideas. Of course, the failed putsch had greatly contributed to Hitler’s genuine distrust of the General Staff, as well as to his long-felt ‘class hatred’ of the army’s aristocratic command. On 27 January, during a two-and-a-half-hour Führer conference, starting at 4.20 p.m., Hitler explained his thinking concerning the Balkans, and in particular, the oilfields of the Lake Balaton region in Hungary. With Göring, Keitel, Jodl, Guderian and five other generals in attendance, together with fourteen other officials, he ranged over every front of the war, with the major parts of the agenda including the weather conditions, Army Group South in Hungary, Army Group Centre in Silesia, Army Group Centre in Silesia, Army Group Vistula in Pomerania, Army Group Kurland, the Eastern Front in general, the west and the war at sea. Guderian told Hitler that our main problem is the fuel issue at the moment, to which Hitler replied, who replied: That’s why I’m concerned, Guderian. Pointing to the Balaton region, he added:

… if something happens down there, it’s over. That’s the most dangerous point. We can improvise everywhere else, but not there. I can’t improvise with the fuel.

The Sixth Panzer Army, reconstituted after its exertions in the Ardennes offensive was ordered to Hungary, from where it could not be extracted. ‘Defending’ Hungary, or rather its oilfields, accounted for seven out of the eighteen Oder-Neisseanzer divisions still available to Hitler on the Eastern Front, a massive but necessary commitment. In January, Hitler had only 4,800 tanks and 1,500 combat aircraft in the east, to fight Stalin’s fourteen thousand tanks and fifteen thousand aircraft. Soon after the conference, Zhukov reached the Oder river on 31 January and Konyev reached the Oder-Neisse Line a fortnight later, on the lower reaches of the River Oder, a mere forty-four miles from the suburbs of Berlin. It had been an epic advance but had temporarily exhausted the USSR, halting its offensive due to the long lines of supply and communications. On 26 February, the Soviets also broke through from Bromberg to the Baltic. As a consequence, East Prussia was cut off from the Reich. Then they didn’t move from their positions until mid-April.

Below: The Liberation of Europe, East & West, January 1944 – March 1945

About twenty million of the war dead were Russians by this stage, together with another seven million from the rest of the USSR, rather more of them civilians than Red Army soldiers. The vast majority of them had died far from any battlefield. Starvation, slave-labour conditions, terror and counter-terror had all played their part, with Stalin probably responsible for nearly as many of the deaths of his own people as Hitler was. However, the Nazis were guilty of the maltreatment of prisoners-of-war, with only one million of the six million Russian soldiers captured surviving the war, as well as millions of Russian Jews. Yet despite their exhaustion, the proximity of Stalin’s troops to the German capital gave their Marshal and leader a greatly increased voice at the Yalta Conference in the Crimea, called to discuss the ‘endgame’ in Europe, and to try to persuade the Soviets to undertake a major involvement in the war against Japan.

The ‘Big Three’ at the Yalta Conference, 4-11 February:

Franklin Roosevelt and Josef Stalin met only twice, at the Tehran Conference in November 1943 and the Yalta Conference in February 1945, although they maintained a very regular correspondence. Roosevelt’s last letter to the Soviet leader was sent on 11 April, the day before he died. By the time of Yalta, it was Roosevelt who was making all the running, attempting to keep the alliance together. With the Red Army firmly in occupation of Poland, and Soviet troops threatening Berlin itself when the conference opened, there was effectively nothing that either FDR or Churchill could have done to safeguard political freedom in eastern Europe, and both knew it. Roosevelt tried everything, including straightforward flattery, to try to bring Stalin round to a reasonable stance on any number of important post-war issues, such as the creation of a meaningful United Nations, but he overestimated what his undoubted aristocratic charm could achieve with the genocidal son of a drunken Georgian cobbler. A far more realistic approach to dealing with Stalin had been adopted by Churchill in Moscow in October 1944, when he took along what he called a naughty document which listed the proportional interest in five central and south-east European countries. Crucially, both Hungary and Yugoslavia would be under ’50-50′ division of influence between the Soviets and the British. Stalin signed the document with a big blue tick, telling Churchill to keep it, and generally stuck to the agreements, the exception being Hungary.

In preparation for the conference, Stalin tried to drum up as much support as he could for his puppet government in Poland. It was a subject, for example, that had dominated the visit of General de Gaulle to Moscow in December 1944. It was against the diplomatic background of this meeting with De Gaulle and in the knowledge that the war was progressing towards its end, that Stalin boarded a train from Moscow for the Crimea in February 1945. He had just learnt that Marshal Zhukov’s Belorussian Front had crossed into Germany and were now encamped on the eastern bank of the Oder. In the West, he knew that the Allies had successfully repulsed Hitler’s counter-attack in the Ardennes, and in the Far East that General Douglas MacArthur was poised to recapture Manila in the Philippines, the British had forced the Japanese back in Burma, and the US bombers were pounding the home islands of Japan. Victory now seemed certain, though it was still uncertain as to how soon and at what cost that victory would come.

The conference at Yalta has come to symbolise the sense that somehow ‘dirty deals’ were done as the war came to an end, dirty deals that brought dishonour on the otherwise noble enterprise of fighting the Nazis. But it wasn’t quite the case. In the first place, of course, it was the Tehran Conference in November 1943 that the fundamental issues about the course of the rest of the war and the challenges of the post-war world and the challenges of the post-war world were initially discussed and resolved in principle. Little of new substance was raised at Yalta. Nonetheless, Yalta is important, not least because it marks the final high point of Churchill and Roosevelt’s optimistic dealings with Stalin. On 3 February, the planes of the two western leaders flew in tandem from Malta to Saki, on the flat plains of the Crimea, north of the mountain range that protects the coastal resort of Yalta. They, and their huge group of advisers and assistants, around seven hundred people in all, then made the torturous drive down through the high mountain passes to the sea.

The main venue for the conference was the tsarist Livadia Palace, where FDR stayed and where the plenary sessions took place. The British delegation stayed at the Vorontsov Villa Palace overlooking the Black Sea at Alupka, twelve miles from the Livadia Palace. The Chiefs of Staff meetings were held at Stalin’s headquarters, the Yusupov Villa at Koreiz, six miles from the Livadia Palace. Churchill, who had cherished the hope that the United Kingdom would be chosen as the site of the conference, was not enthusiastic about the Crimea. He later described the place as ‘the Riviera of Hades’ and said that…

… if we had spent ten years on research, we could not have found a worse place in the world.

But, as in so much else, the will of Stalin had prevailed, and none of the Western Allies seemed aware of of the bleak irony that his chosen setting was the very location where eight months previously Stalin his own peculiar way of dealing with dissent, real or imagined, in deporting the entire Tatar nation. Yet it was here in the Crimea that the leaders were about to discuss the futures of many nationalities and millions of people. One of these leaders, President Roosevelt, had, according to Churchill’s doctor, Lord Moran, gone to bits physically. He doubted whether the President was fit for the job he had to do at Yalta. Hugh Lunghi, who went to the military mission in Moscow, remembers seeing the two leaders arrive by plane, and he too was surprised by the President’s appearance:

Churchill got out of his aircraft and came over to Roosevelt’s. And Roosevelt was being decanted, as it were – it’s the only word I can use – because of course he was disabled. And Churchill looked at him very solicitously. They’d met in Malta of course, so Churchill, I suppose, had no surprise, as I had – and anyone else had who hadn’t seen Roosevelt previously – to see this gaunt, very thin figure with his black cape over his shoulder, and tied at his neck with a knot, and his trilby hat turned up at the front. His face was waxen to a sort of yellow … and very drawn, very thin, and a lot of the time he was sort of … sitting there with his mouth open sort of staring ahead. So that was quite a shock.

Roosevelt was a dying man at Yalta, but whether his undoubted weakness affected his judgement is less easy to establish, with contemporary testimony supporting both sides of the argument. What is certain, though, is that Roosevelt’s eventual accomplishments at Yalta were coherent and consistent with his previous policies as expressed at Tehran and elsewhere. His principal aims remained those of ensuring that the Soviet Union came into the war against Japan, promptly, once the war in Europe was over and gaining Soviet agreement about the United Nations. The intricacies of the borders of eastern Europe mattered much less to him. Addressing Congress in March 1945, Roosevelt reported that Yalta represented:

… the end of the system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balance of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries, and have always failed.

This was an idealistic, perhaps naive, way to have interpreted the Yalta conference, but it is quite possible that Roosevelt believed what he was saying when he said it, regardless of disability and illness. Whilst Roosevelt’s physical decline was obvious for all present to see, just as obvious was Stalin’s robust strength and power. As the translator at the Conference, Hugh Lunghi saw him:

Stalin was full of beans … He was smiling, he was genial to everyone, and I mean everybody, even to junior ranks like myself. He joked at the banquets more than he he had before.

In his military uniform, Stalin cut an imposing figure, and, in the head of the British Foreign Office, Sir Alexander Cadogan’s words, he was quiet and restrained, with a very good sense of humour and a rather quick temper. But, more than that, the Allied leaders felt that Stalin at Yalta was someone they could relate to on a personal level and could trust more than they had been able to do previously. Certainly, Churchill and Roosevelt remained anxious to believe in Stalin the man. They clung to the hope that Stalin’s previous statements of friendship meant that he was planning on long-term co-operation with the West. By the time of Yalta, Churchill could point to the fact that the Soviets had agreed to allow the British a free hand in Greece. In any case, the future peace of the world still depended on sustaining a productive relationship with Stalin. The two Western leaders remained predisposed to gather what evidence they could in support of their jointly agreed ‘thesis’ that Stalin was a man they could ‘handle’. At the first meeting of all three leaders, in the Livadia Palace, the former holiday home of the imperial family, Roosevelt remarked:

… we understand each other much better now than we had in the past and that month by month that understanding was growing.

It was Poland which was to be the test case for this assertion, and no subject was discussed more at Yalta. Despite the protests of the Polish government in exile, both Roosevelt and Churchill had already agreed that Stalin could keep eastern Poland. What mattered to both leaders was that the new Poland, within its new borders, should be ‘independent and free’. They knew only too well, of course, that only days after Hitler’s ‘brutal attack’ from the West, the Soviet Union had made their own ‘brutal attack’ from the East. It was the results of this ‘land grab’ that Churchill now agreed, formally, to accept. But he also explained that Britain had gone to war over Poland so that it could be “free and sovereign” and that this was a matter of “honour” for Britain. Stalin pointed out that twice in the last thirty years, the USSR had been attacked through the “Polish corridor”, and he remarked:

The Prime Minister has said that for Great Britain the question of Poland is a question of honour. For Russia it is not only a question of honour but also of security … it is necessary that Poland be free, independent and powerful. … there are agents of the London government connected with the so-called underground. They are called resistance forces. We have heard nothing good from them but much evil.

Stalin, therefore, kept to his position that the ‘Lublin Poles’, who were now in the Polish capital as ‘the Polish government’ had as great a democratic base in Poland as de Gaulle has in France and that elements of the ‘Home Army’ were ‘bandits’ and that the ex-Lublin Poles should be recognised as the legitimate, if temporary, government of Poland. Unlike at Tehran, where he had remained silent in the face of Stalin’s accusations about the Polish resistance, Churchill now made a gentle protest:

I must put on record that the British and Soviet governments have different sources of information in Poland and get different facts. Perhaps we are mistaken but I do not feel that the Lublin government represents even one third of the Polish people. This is my honest opininion and I may be wrong. Still, I have felt that the underground might have collisions with the Lublin government. I have feared bloodshed, arrests, deportation and I fear the effect on the whole Polish question. Anyone who attacks the Red Army should be punished but I cannot feel the Lublin government has any right to represent the Polish nation.

As Churchill and Roosevelt saw it, the challenge was to do what they could to ensure that the government of the newly reconstituted country was as representative as possible. So Roosevelt sent Stalin a letter after the session that he was concerned that people at home look with a critical eye on what they consider a disagreement between us at this vital stage of the war. He also stated categorically that we cannot register the Lublin government as now composed. Roosevelt also proposed that representatives of the ‘Lublin Poles’ and the ‘London Poles’ be immediately called to Yalta s that ‘the Big Three’ could assist them in jointly agreeing on a provisional government in Poland. At the end of the letter, Roosevelt wrote that:

… any interim government which could be formed as a result of our conference with the Poles here would be pledged to the holding of free elections in Poland at the earliest possible date. I know this is completely consistent with your desire to see a new free and democratic Poland emerge from the welter of this war.

This put Stalin in something of an awkward spot because it was not in his interests to have the composition of any interim government of Poland worked out jointly with the other Allied leaders. He would have to compromise his role, as he saw it, as the sole driver of events if matters were left until after the meeting disbanded. So he first practised the classic politicians’ ploy of delay. The day after receiving Roosevelt’s letter, 7 February, he claimed that he had only received the communication ‘an hour and a half ago’. He then said that he had been unable to reach the Lublin Poles because they were away in Kraków. However, he said, Molotov had worked out some ideas based on Roosevelt’s proposals, but these ideas had not yet been typed out. He also suggested that, in the meantime, they turn their attention to the voting procedure for the new United Nations organisation. This was a subject dear to Roosevelt’s heart, but one which had proved highly problematic at previous meetings. The Soviets had been proposing that each of the sixteen republics should have their own vote in the General Assembly, while the USA would have only one. They had argued that since the British Commonwealth effectively controlled a large number of votes, the Soviet Union deserved the same treatment. In a clear concession, Molotov said that they would be satisfied with the admission of … at least two of the Soviet Republics as original members. Roosevelt declared himself ‘very happy’ to hear these proposals and felt that this was a great step forward which would be welcomed by all the peoples of the World. Churchill also welcomed the proposal.

Then Molotov presented the Soviet response on Poland, which agreed that it would be desirable to add to the Provisional Polish Government some democratic leaders from the Polish émigré circles. He added, however, that they had been unable to reach the Lublin Poles, so that time would not permit their summoning to Yalta. This was obviously a crude ruse not to have a deal brokered between the two Polish ‘governments’ at Yalta in the presence of the Western leaders. Yet Churchill responded to Molotov’s proposal only with a comment on the exact borders of the new Poland, since the Soviet Foreign Minister had finally revealed the details of the boundaries of the new Poland, as envisaged by the Soviets, with the western border along the rivers Oder and Neisse south of Stettin. This would take a huge portion of Germany into the new Poland, and Churchill remarked that it would be a pity to stuff the Polish goose so full of German food that it got indigestion. This showed that the British were concerned that so much territory would be taken from the Germans that in the post-war world they would be permanently hostile to the new Poland, thus repeating the mistakes made at Versailles in 1919 and forcing the Poles closer to the Soviets.

At this conference, Churchill couched this concern as anxiety about the reaction of a considerable body of British public opinion to the Soviet plan to move large numbers of Germans. Stalin responded by suggesting that most Germans in these regions had already run away from the Red Army. By these means, Stalin successfully dodged Roosevelt’s request to get a deal agreed between the Lublin and London Poles. After dealing with the issue of Soviet participation in the Pacific War, the leaders returned once more to the question of Poland. Churchill saw this as the crucial point in this great conference and, in a lengthy speech, laid out the immensity of the problem faced by the Western Allies:

We have an army of 150,000 Poles who are fighting bravely. That army would not be reconciled to Lublin. It would regard our action in transferring recognition as a betrayal.

Above: Stalin & Churchill at Yalta

Churchill acknowledged that, if elections were held with a fully secret ballot and free candidacies, this would remove British doubts. But until that happened, and with the current composition of the Lublin government, the British couldn’t transfer its allegiance from the London-based Polish government-in-exile. Stalin, in what was a speech laced with irony, retorted:

The Poles for many years have not liked Russia because Russia took part in three partitions of Poland. But the advance of the Soviet Army and the liberation of Poland from Hitler has completely changed that. The old resentment has completely disappeared … my impression is that the Polish people consider this a great historic holiday.

The idea that the members of the Home Army, for example, were currently being treated to a ‘historic holiday’ can only have been meant as ‘black’ humour. But Churchill made no attempt to correct Stalin’s calumny. In the end, the Western Allies largely gave in to Stalin’s insistence and agreed that the Soviet-Polish border and, in compensation to Poland, that the Polish-German border should also shift westward. Stalin did, however, say that he agreed with the view that the Polish government must be democratically elected, adding that it is much better to have a government based on free elections. But the final compromise the three leaders came to on Poland was so biased in favour of the Soviets that it made this outcome extremely unlikely. Although Stalin formally agreed to free and fair elections in Poland, the only check the Western Allies secured on this was that ‘the ambassadors of the three powers in Warsaw’ would be charged with the oversight of the carrying out of the pledge in regard to free and unfettered elections. On the composition of the interim government, the Soviets also got their own way. The Western Allies only ‘requested’ that the Lublin government be reorganised to include ‘democratic’ leaders from abroad and within Poland. But the Soviets would be the conveners of meetings in Moscow to coordinate this. It’s difficult to believe that Roosevelt and Churchill could have believed that this ‘compromise’ would work in producing a free and democratic Poland, their stated aim. Hugh Lunghi later reflected on the generally shared astonishment:

Those of us who worked and lived in Moscow were astounded that a stronger declaration shouldn’t have been made, because we knew that there was not a chance in hell that Stalin would allow free elections in those countries when he didn’t allow them in the Soviet Union.

This judgement was shared at the time by Lord Moran, who believed that the Americans at Yalta were ‘profoundly ignorant’ of ‘the Polish problem’ and couldn’t fathom why Roosevelt thought he could ‘live at peace’ with the Soviets. Moran felt that it had been all too obvious in Moscow the previous October that Stalin meant to make Poland ‘a Cossack outpost of Russia’. He saw no evidence at Yalta that Stalin had ‘altered his intention’ since then. But on his first observation, he was wrong in respect to Roosevelt, at least. The President no longer cared as much about Poland as he had done when needing the votes of Polish Americans to secure his third term. He now gave greater priority to other key issues, while paying lip-service to the view that the elections in Poland had to be free and open. He told Stalin, …

… I want this election to be the first one beyond question … It should be like Caesar’s wife. I didn’t know her but they say she was pure.

Privately, the President acknowledged that the deal reached on Poland was far from perfect. When Admiral Leahy told him that it was so elastic that the Russians can stretch it all the way from Yalta to Washington without ever technically breaking it, Roosevelt replied: I know, Bill, but it is the best I can do for Poland at this time. The ‘deal’ was the best he could do because of the low priority he gave to the issue at that particular time. What was most important for Roosevelt overall was that a workable accommodation was reached with Stalin on the key issues which would form the basis for the general post-war future of the world. He did not share the growing consensus among the Americans living in Russia that Stalin was as bad as Hitler. Just before Yalta, he had remarked to a senior British diplomat that there were many varieties of Communism, and not all of them were necessarily harmful. As Moran put it, I don’t think he has ever grasped that Russia is a Police State. For the equally hard-headed Leahy, the consequences of Yalta were clear the day the conference ended, 11 February. The decisions taken there would result in Russia becoming …

… the dominant power in Europe, which in itself carries a certainty of future international disagreements and the prospects of another war.

But by the end of the conference, the leaders of the Western Allies and many of their key advisers were clearly putting their faith ever more firmly in the individual character of Stalin. Cadogan wrote in his journal on 11th that he had …

… never known the Russians so easy and accommodating … In particular, Joe has been extremely good. He is a great man, and shows up very impressively against the background of the other two ageing statesmen.

Churchill remarked that what had impressed him most was that Stalin listened carefully to counter-arguments and was then prepared to change his mind. And there was other evidence of a practical nature that could be used to demonstrate Stalin’s desire to reach an accommodation with the West – his obvious intention not to interfere in British action in Greece, for example. But above all, it was the impact of his personality and behaviour during the conference that was crucial in the optimism that prevailed straight after Yalta. This was evident in the signing of the ‘somewhat fuzzy’ Declaration on Liberated Europe, which pledged support for reconstruction and affirmed the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live. There was, at least in public, a sense that the ideological gap between the West and the Soviet Union was closing, with renewed mutual respect. Drained by long argument, the West, for now at least, took Stalin at his word. At the last banquet of the conference, Stalin toasted Churchill as the bravest governmental figure in the world. He went on:

Due in large measure to to Mr Churchill’s courage and staunchness, England, when she stood alone, had divided the might of Hitlerite Germany at a time when the rest of Europe was falling flat on its face before Hitler. … he knew of few examples in history where the courage of one man had been so important to the future history of the world. He drank a toast to Mr Churchill, his fighting friend and a brave man.

Verdicts on Yalta & Reactions in Britain and the USA:

In his ‘ground-breaking’ TV series on ‘the Cold War’, Jeremy Isaacs considered that:

The Yalta Conference represented the high-water mark of Allied wartime collaboration … But Yalta was also the beginning of the post-war world; the divisions between East and West became apparent. …

Stalin was apprehensive that the new United Nations might be controlled by the United States and Britain, and that the Soviet Union would be outnumbered there. It was agreed that two or three Soviet republics would be admitted as members and that each of the great powers should have a veto over resolutions of the Security Council.

However, the Western powers might have bargained differently and more effectively at Yalta. The Americans never used their considerable economic power to try to pressurise the Soviets to be more accommodating. The Soviets wanted a $6 billion line of credit to buy American equipment after the war, as well as an agreement on the amount of reparation they could take from Germany to pay for the conflict. They saw this partly as compensation for the vast destruction caused by the Nazis, partly as a means of punishing the German people for following them and partly as a symbol of victor’s rights. Britain and the United States were opposed to reparations; they had caused havoc after the First World War and could now hinder Germany from recovering following the Second. Eventually, after Yalta, they did agree to them, and Roosevelt compromised on a figure of $20 billion, to be paid in goods and equipment over a reasonable period of time. Neither of these issues was properly discussed at Yalta, however, not least because most people involved thought that there would be a formal peace conference at the end of the war to resolve all the key issues once and for all. But such a conference would never take place. According to Jeremy Isaacs, …

Yalta revealed cracks in the Grand Alliance. Only the common objective of defeating Hitler had kept it together; that and the personal trust, such as it was, among the three leaders.

After Yalta, the relationship between Roosevelt and Stalin would be the key to co-operation. With victory in sight, on 12 April, having defused another dispute with Stalin, the president drafted a cable to Churchill: I would minimise the general Soviet problem. Later the same day, and a little over two months after Yalta, Roosevelt collapsed, and a few hours later he was dead.

For the most part, the three statesmen were pleased with what had been accomplished at the Yalta Conference. As well as the agreements on Poland, albeit without the consent of the Polish people themselves or the Polish government-in-exile, the demarcation zones for occupied Germany had been fixed, with the French being granted an area of occupation alongside the British, Americans and Soviets. Yet, notwithstanding the discussions of the subject at the conferences held at both Tehran and Yalta, there was no unified conception of the occupying forces regarding the future treatment of Germany before its surrender. What was ‘tidied up’ on the conference fringe were the military plans for the final onslaught on Nazi Germany. It was also agreed that German industry was to be shorn of its military potential, and a reparations committee was set up. Also, major war criminals were to be tried, but there was no discussion of the programme of ‘denazification’ which was to follow. Neither did Stalin disguise his intention to extend Poland’s frontier with Germany up to the Oder-Neisse line, despite the warnings given by Churchill at the conference about the effects this would have on public opinion in the West.

However, the initial reactions in Britain were concerned with Poland’s eastern borders. Immediately after the conference, twenty-two Conservative MPs put down an amendment in the House of Commons remembering that Britain had taken up arms in defence of Poland and regretting the transfer of the territory of an ally, Poland, to ‘another power’, the Soviet Union; noting also the failure of the to ensure that these countries liberated by the Soviet Union from German oppression would have the full rights to choose their own form of government free from pressure by another power, namely the Soviet Union. Harold Nicolson, National Labour MP and former Foreign Office expert, voted against the amendment: I who had felt that Poland was a lost cause, feel gratified that we had at least saved something. Praising the settlement as the most important political agreement we have gained in this war, he considered the alternatives. To stand aside, to do nothing, would be ‘unworthy of a great country’. Yet to oppose the Russians by force would be insane. The only viable alternative was ‘to save something by negotiation’. The Curzon Line, delineated after ‘a solid, scientific examination of the question’ at the Paris Peace Conference was, he claimed, ‘entirely in favour of the Poles’. Should Poland advance beyond that line, ‘she would be doing something very foolish indeed’. Churchill and Eden came in for the highest praise:

When I read the Yalta communiqué, I thought “How could they have brought that off? This is really splendid!”

Turning the dissident Conservatives’ amendment on its head, Harold Nicolson revealed Yalta’s most lasting achievement. Russia, dazzled by its military successes, revengeful and rapacious, might well have aimed to restore its ‘old Tsarist frontiers’. It had not done so and instead had agreed to modify them permanently. Harold Nicolson spoke with conviction in the Commons, but then to salute Stalin’s perceived altruism in the Polish matter rendered his reasoning contrived and decidedly off-key. The truth, as Churchill would tell him on his return from Yalta, was much more prosaic. Stalin had dealt himself an unbeatable hand, or, as two Soviet historians in exile put it: The presence of 6.5 million Soviet soldiers buttressed Soviet claims. But then, Churchill’s own rhetoric was not all it seemed to be. Although in public he could talk about the moral imperative behind the war, in private he revealed that he was a good deal less pure in his motives. On 13 February, on his way home from Yalta, he argued with Field Marshal Alexander, who was ‘pleading’ with him that the British should provide more help with post-war reconstruction in Italy. Alexander said that this was more or less what we are fighting this war for – to secure liberty and a decent existence for the peoples of Europe. Churchill replied, Not a bit of it! We are fighting to secure the proper respect for the British people!

Nicolson’s warm support of the Yalta agreement rested on the rather woolly ‘Declaration on Liberated Europe’ promising national self-determination, of which he said:

No written words could better express the obligation to see that the independence, freedom and integrity of Poland of the future are preserved.

He also thought that Stalin could be trusted to carry out his obligations since he had demonstrated that he is about the most reliable man in Europe. These sentiments, to a generation born into the Cold War, and especially those brought up in the ‘satellite’ states of eastern-central Europe, must sound alarmingly naive, but at that time he was in good company. On returning from Yalta, Churchill reported to his Cabinet. He felt convinced that Stalin ‘meant well in the world and to Poland’ and he had confidence in the Soviet leader to keep his word. Hugh Dalton, who attended the Cabinet meeting, reported Churchill as saying:

Poor Neville Chamberlain believed he could trust Hitler. He was wrong. But I don’t think I’m wrong about Stalin.

Opposition to Yalta was muted, confined mainly to discredited ‘Munichites’ who now sprang to the defence of Poland. In the Commons on 27 February Churchill continued to put the best gloss he could on the conference, and said he believed that:

Marshal Stalin and the Soviet leaders wish to live in honourable friendship and equality with the Western democracies. I feel also that their word is their bond.

When the Commons voted 396 to 25 in favour of Churchill’s policy, the PM was ‘overjoyed’, praising Nicolson’s speech as having swung many votes. Churchill’s faith in Stalin, shared by Nicolson, proved right in one important respect. The ‘percentages agreement’ he had made with Stalin in Moscow by presenting him with his ‘naughty document’, which had been signed off at Yalta, was, at first, ‘strictly and faithfully’ adhered to by Stalin, particularly in respect of Greece.

Roosevelt’s administration went further. In Washington, the President was preceded home by James Byrnes, then head of the war mobilization board and later Truman’s Secretary of State, who announced not only that agreement had been reached with at Yalta about the United Nations, but that as a result of the conference, ‘spheres of influence’ had been eliminated in Europe, and the three great powers are going to preserve order (in Poland) until the provisional government is established and elections held. This second announcement was, of course, very far from the truth which was that degrees or percentages of influence had been confirmed at Yalta. Roosevelt had wanted the American public to focus on what he believed was the big achievement of Yalta – the agreement over the foundation and organisation of the United Nations. The President, well aware that he was a sick man, wanted the UN to be central to his legacy. He would show the world that he had taken the democratic, internationalist ideals of Woodrow Wilson which had failed in the League of Nations of the inter-war years, and made them work in the shape of the UN.

The ‘gloss’ applied to the Yalta agreement by both Roosevelt and Byrnes was bound to antagonise Stalin. The Soviet leader was the least ‘Wilsonian’ figure imaginable. He was not an ‘ideas’ man but believed in hard, practical reality. What mattered to him was where the Soviet Union’s borders were and the extent to which neighbouring countries were amenable to Soviet influence. The response of Pravda to Byrnes’ spin was an article on 17 February that emphasised that the word ‘democracy’ meant different things to different people and that each country should now exercise ‘choice’ over which version it preferred. This, of course, was a long way from Roosevelt’s vision, let alone that of Wilson. In fact, the Soviets were speaking the language of ‘spheres of influence’, the very concept which Byrnes had just said was now defunct. Stalin had consistently favoured this concept for the major powers in Europe and this was why he was so receptive towards Churchill’s percentages game in October 1944.

But it would be a mistake to assume that Stalin, all along, intended that all the eastern European states occupied by the Red Army in 1944-45 should automatically transition into Soviet republics. What he wanted all along were ‘friendly’ countries along the USSR’s border with Europe within an agreed Soviet ‘sphere of influence’. Of course, he defined ‘friendly’ in a way that precluded what the Western Allies would have called ‘democracy’. He wanted those states to guarantee that they would be close allies of the USSR so that they would not be ‘free’ in the way Churchill and Roosevelt envisaged. But they need not, in the immediate post-war years, become Communist states. However, it was Churchill, rather than the other two of the ‘Big Three’ statesmen, who had the most difficulty in ‘selling’ Yalta. That problem took physical form in the shape of General Anders, who confronted Churchill face to face on 20 February. The Polish commander had been outraged by the Yalta agreement, which he saw as making a ‘mockery of the Atlantic Charter’. Churchill said that he assumed that Anders was not satisfied with the Yalta agreement. This must have been heard as a deliberate understatement, as Anders replied that it was not enough to say that he was dissatisfied. He said: I consider a great calamity has occurred. He then went on to make it clear to Churchill that his distress at the Yalta agreement was not merely idealistic, but had a deeply practical dimension as well. He protested:

Our soldiers fought for Poland. Fought for the freedom of their country. What can we, their commanders, tell them now? Soviet Russia, until 1941 in close alliance with Germany, now takes half our territory, and in the rest of it she wants to establish her power.

Churchill became annoyed at this, blaming Anders for the situation because the Poles could have settled the eastern border question earlier. He then added a remarkably hurtful remark, given the sacrifice made by the Poles in the British armed forces:

We have enough troops today. We do not need your help. You can take your divisions. We shall do without them.

It is possible to see in this brief exchange not only Churchill’s continuing frustration with the Poles but also the extent to which he felt politically vulnerable because of Yalta. His reputation now rested partly on the way Stalin chose to operate in Poland and the other eastern European countries. To preserve intact his own wartime record, he had to hope Stalin would keep to his ‘promises’. Unfortunately for the British Prime Minister, this hope would shortly be destroyed by Soviet action in the territory they now occupied. Anders (pictured on the right after the Battle of Monte Casino) talked to Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff. In his diary entry for 22 February, the latter recorded what Anders told him, explaining why the Polish leader takes this matter so terribly hard:

After having been a prisoner, and seeing how Russians could treat Poles, he considered that he was in a better position to judge what Russians were like than the President or PM. … When in a Russian prison he was in the depth of gloom but he did then always have hope. Now he could see no hope anywhere. Personally his wife and children were in Poland and he could never see them again, that was bad enough. But what was infinitely worse was the fact that all the men under his orders relied on him to find a solution to this insoluble problem! … and he, Anders, saw no solution and this kept him awake at night.

It soon became clear that Anders’ judgement of Soviet intentions was an accurate one, as Stalin’s concept of ‘free and fair elections’ was made apparent within a month. But even before that, in February, while the ‘Big Three’ were determining their future of without them and Churchill was traducing their role of in the war, the arrests of Poles by the Soviets continued, with trainloads of those considered ‘recalcitrants’ sent east, including more than 240 truckloads of people from Bialystok alone.

The Combined Bombing Offensive & the Case of Dresden:

Meanwhile, from the beginning of February, German west-to-east troop movements were being disrupted at the Russians’ urgent request for the Western Allies to bomb the nodal points of Germany’s transportations system, including Berlin, Chemnitz, Leipzig and Dresden. But it was to be the raid on Dresden in the middle of the month that was to cause the most furious controversy of the whole Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO), a controversy which has continued to today. During the Yalta Conference of 4 to 11 February, Alan Brooke chaired the Chiefs of Staff meetings at the Yusupov Villa the day after the opening session when the Russian Deputy Chief of Staff Alexei Antonov and the Soviet air marshal Sergei Khudyakov pressed the subject of bombing German lines of communication and entrainment, specifically via Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden. In the view of one of those present, Hugh Lunghi, who translated for the British Chiefs of Staff during these meetings with the Soviets, it was this urgent request to stop Hitler transferring divisions from the west to reinforce his troops in Silesia, blocking the Russian advance on Berlin that led directly to the bombing of Dresden only two days after the conference ended.

The massive attack on Dresden took place just after ten o’clock on the night of Tuesday, 13 February 1945 by 259 Lancaster bombers from RAF Swinderby in Lincolnshire, as well as from other nearby airfields, flying most of the way in total cloud, and then by 529 more Lancasters a few hours later in combination with 529 Liberators and Flying Fortresses of the USAAF the next morning. It has long been assumed that a disproportionately large number of people died in a vengeance attack for the November 1940 ‘blanket bombing’ of Coventry and that the attack had little to do with any strategic or military purpose. Yet though the attack on the beautiful, largely medieval city centre, ‘the Florence of the Elbe’, was undeniably devastating, there were, just as in Coventry, many industries centred in this architectural jewel of southern Germany.

The 2,680 tons of bombs dropped laid waste to over thirteen square miles of the city, and many of those killed were women, children, the elderly and some of the several hundred thousand refugees fleeing from the Red Army, which was only sixty miles to the east. The military historian Allan Mallinson has written of how those killed were suffocated, burnt, baked or boiled. Piles of corpses had to be pulled out of a giant fire-service water-tank into which people had jumped to escape the flames but were instead boiled alive. David Irving’s 1964 book The Destruction of Dresden claimed that 130,000 people died in the bombing, but this has long been disproven. The true figure was around twenty thousand, as a special commission of thirteen prominent German historians concluded, although some more recent historians have continued to put the total at upwards of fifty thousand. Propaganda claims by the Nazis at the time, repeated by neo-Nazis more recently, that human bodies were completely ‘vaporised’ in the high temperatures were also shown to be false by the commission.

Certainly, by February 1945, the Allies had discovered the means to create firestorms, even in cold weather very different from that of Hamburg in July and August of 1943. Huge ‘air mines’ known as ‘blockbusters’ were dropped, designed to blow out windows and doors so that the oxygen would flow through easily to feed the flames caused by the incendiary bombs. High-explosive bombs both destroyed buildings and just as importantly kept the fire-fighters down in their shelters. One writer records:

People died not necessarily because they were burnt to death, but also because the firestorm sucked all the oxygen out of the atmosphere.

In Dresden, because the sirens were not in proper working order, many of the fire-fighters who had come out after the first wave of bombers were caught out in the open by the second. Besides this, the Nazi authorities in Dresden, and in particular its Gauleiter Martin Mutschmann, had failed to provide proper air-raid protection. There were inadequate shelters, sirens failed to work and next to no aircraft guns were stationed there. When Mutschmann fell into Allied hands at the end of the war he quickly confessed that a shelter-building programme for the entire city was not carried out because he hoped that nothing would happen to Dresden. Nonetheless, he had two deep reinforced built for himself, his family and senior officials, just in case he had been mistaken. Even though the previous October 270 people had been killed there by thirty USAAF bombers, the Germans thought Dresden was too far east to be reached, since the Russians left the bombing of Germany almost entirely to the British and Americans. Quite why Mutschmann thought that almost alone of the big cities, Dresden should have been immune to Allied bombing is a mystery, for the Germans had themselves designated it as a ‘military defensive area’.

So the available evidence does not support the contemporary view of Labour’s Richard Stokes MP and Bishop George Bell as a ‘war crime’, as many have since assumed that it was. As the foremost historian of the operation, Frederick Taylor has pointed out, Dresden was by the standards of the time a legitimate military target. As a nodal point for communications, with its railway marshalling yards and conglomeration of war industries, including an extensive network of armaments workshops, the city was always going to be in danger once long-range penetration by bombers with good fighter escort was possible. One historian has asked: Why is it legitimate to kill someone using a weapon, and a crime to kill those who make the weapons? However, Churchill could see that the ‘CBO’ would provide a future line of attack against his prosecution of the war, and at the end of March, he wrote to the Chiefs of Staff to put it on record that:

… the question of bombing German cities simply for the the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed. Otherwise we shall come into control of an utterly ruined land. We shall not, for instance, be able to get housing materials out of Germany for our own needs because some temporary provisions would have to be made for the Germans themselves. The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing … I feel the need for more precise concentration upon military objectives … rather than on mere acts of terror and wanton destruction, however impressive.

This ‘minute’ has been described as sending a thunderbolt down the corridors of Whitehall. ‘Bomber’ Harris, who himself had considerable misgivings about the operation because of the long distances involved, was nonetheless characteristically blunt in defending the destruction of a city that once produced Meissen porcelain:

The feeling, such as there is, over Dresden could be easily explained by a psychiatrist. It is connected with German bands and Dresden shepherdesses. Actually Dresden was a mass of munition works, an intact government centre and a key transportation centre. It is now none of those things.

One argument made since the war, that the raid was unnecessary because peace was only ten weeks off, is especially ahistorical. With talk of secret weaponry, a Bavarian Redoubt, fanatical Hitler Youth ‘werewolf’ squads and German propaganda about fighting for every inch of the Fatherland, there was no possible way of the Allies knowing how fanatical German resistance would be, and thus predict when the war might end. The direct and indirect effects of the bombing campaign on war production throughout Germany reduced the potential output of weapons for the battlefields by fifty per cent. The social consequences of bombing also reduced economic performance. Workers in cities spent long hours huddled in air-raid shelters; they arrived for work tired and nervous. The effects of bombing in the cities also reduced the prospects of increasing female labour as women worked to salvage wrecked homes, or took charge of evacuated children, or simply left for the countryside where conditions were safer. In the villages, the flood of refugees from bombing strained the rationing system, while hospitals had to cope with three-quarters of a million casualties. Under these circumstances, demoralisation was widespread, though the ‘terror state’ and the sheer struggle to survive prevented any prospect of serious domestic unrest.

The Reich fragmented into several self-contained economic areas as the bombing destroyed rail and water transport. Factories lived off accumulated stocks. By the end of February, the economy was on the verge of collapse, as the appended statistics reveal. Meanwhile, German forces retreated to positions around Berlin, preparing to make a last-ditch stand in defence of the German capital.

Statistical Appendix: The Social & Economic Consequences of the Bombing Campaign in Germany:

Sources:

Published in 2008, by BBC Books, an imprint of Ebury Books, London.

Andrew Roberts (2009), The Storm of War: A New History of the Second World War. London: Penguin Books.

Norman Rose (2005), Harold Nicolson. London: Pimlico.

Colin McEvedy (1982), The Penguin Atlas of Recent History. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Herman Kinder & Werner Hilgemann (1978), The Penguin Atlas of World History, volume two. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Richard Overy (1996), The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Third Reich. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Jeremy Isaacs & Taylor Downing (1998), Cold War: For Forty-five Years the World Held Its Breath. London: Transworld Publishers.

Posted February 3, 2020 by AngloMagyarMedia in American History & Politics, anti-Communist, Asia, asylum seekers, Austria, Axis Powers, Balkan Crises, Baltic States, BBC, Berlin, Britain, British history, Churchill, Coalfields, Cold War, Communism, Compromise, Conquest, Conservative Party, Coventry, democracy, Deportation, Economics, Empire, Europe, Factories, Family, France, Genocide, Germany, History, Humanitarianism, Hungary, Italy, Japan, manufacturing, Migration, morality, Mythology, Narrative, nationalism, Navy, Poland, Refugees, Russia, Second World War, Security, Stalin, Technology, terror, United Kingdom, United Nations, USA, USSR, Versailles, War Crimes, Warfare, Women at War, Women's History, World War Two, Yugoslavia

Tagged with 'air mines', 'blockbusters', 'Bomber' Harris, 'Grand Alliance', 'Munichites', 'spheres of influence', Admiral Leahy, Alan Brooke, Albert Speer, altruism, Ardennes, Atlantic Charter, Balaton, Baltic, Baranov, Battle of the Bulge, Belorussia, Bialystok, Bishop George Bell, Bradley, Breslau, Bromberg, Burma, Cadogan, Carpathians, Christianity, Churchill, Clausewitz, Cold War, Combined Bomber Offensive, Cossack, Coventry, Crimea, culture, Curzon Line, Dönitz, demoralisation, denazification, Dresden, East Prussia, Eisenhower, Elbe, F.D. Roosevelt, Faith, firestorms, Flying Fortresses, Frederick Taylor, Göring, General Anders, Georgia, Guderian, Hades, Hannibal, Harold Nicolson, History, Hitler Youth 'werewolf' squads, housing, Hugh Dalton, Hugh Lunghi, Irving, Italy, James Byrnes, Kanth, Kurland, Lancaster bombers, League of Nations, Liberators, Livadia, Lublin, Luftwaffe, MacArthur, Mallinson, Meuse, Moltke, Monte Casino, Montgomery, Neville Chamberlain, Oder, Oder-Vistula Offensive, Opperau, Panzers, Paris Peace Conference, Patton, politics, Pomerania, Pravda, RAF, Rationing, Red Army, Reich Chancellery, Richard Stokes MP, Ruhr, Rundstedt, Schlieffen, Silesia, Silesis, society, Swinderby, Tatar nation, Tehran, UN, USA, USAAF, Vistula, Warsaw, Wehrmacht, Whitehall, Woodrow Wilson, Yalta Conference, Yusupov, Zhukov

Undiplomatic ‘Moves’:

In the month following the Second Quebec Conference of 12th-16th September 1944, there was a storm of protest about the Morgenthau Plan, a repressive measure against Germany which Stalin craved. Although he was not present in person at Quebec, Stalin was informed about the nature and detail of the proposals. On 18 October, the Venona code-breakers had detected a message from an economist at the War Production Board to his Soviet spymasters that outlined the plan. This was that:

The Rühr should be wrested from Germany and handed over to the control of some international council. Chemical, metallurgical and electrical industries must be transported out of Germany.

The US Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, was appalled that Morgenthau had been allowed to trespass so blatantly on an area of policy that did not belong to him, and also that the proposed plan would, in his judgment, so clearly result in the Germans resisting more fiercely. With his health failing, Hull resigned in November 1944. The American press was just as antagonistic. Both the New York Times and Washington Post attacked the plan as playing into the hands of the Nazis. And in Germany, the proposals were a gift for Joseph Goebbels, who made a radio broadcast in which he announced:

In the last few days we have learned enough about the enemy’s plans, … The plan proposed by that Jew Morgenthau which would rob eighty million Germans of their industry and turn Germany into a simple potato field.

Roosevelt was taken aback by the scale of the attack on the Morgenthau Plan, realizing that he had misjudged the mood of his own nation, a rarity for him, and allowed a Nazi propaganda triumph. The Plan for the complete eradication of German industrial production capacity in the Ruhr and the Saar was quietly dropped in the radical form in which it had originally been proposed at Quebec, although the punitive philosophy underpinning it later found expression in the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive 1067, which stated that occupation forces should take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany or designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy. At the same time, Roosevelt, comfortably re-elected on 7 November, confidently replied to Mikolajczyk, the Polish PM in exile, who had accused him of bad faith over the future of his country, that if a mutual agreement was reached on the borders of Poland, then his government would offer no objection. Privately, however, the US President considered the European questions so impossible that he wanted to stay out of them as far as practicable, except for the problems involving Germany. Reading between the lines, Mikolajczyk decided that he had heard and seen enough of the West’s unwillingness to face Stalin down. He resigned on 24 November. Just days after his resignation, Churchill confirmed his support for Roosevelt’s ‘line’. He told the Cabinet that:

No immediate threat of war lay ahead of us once the present war was over and we should be careful of assuming commitments consequent on the formation of a Western bloc that might impose a very heavy military burden on us.

Although his views about the stability of the post-war world were still capable of changing, Churchill felt that, on balance, the Soviet Union would prove a genuinely cooperative member of the international community and he returned from Moscow in an upbeat mood. He wrote to his wife Clementine that he had had …

… very nice talks with the old Bear … I like him the more I see him. Now they respect us and I am sure they wish to work with us.

Over the next few months, however, Stalin’s actions on the eastern front would shatter Churchill’s hopes. On 24 November, the Soviets had established a bridgehead over the Danube and a month later, on Christmas Eve, they were encircling Budapest. Defending Hungary accounted for seven of the eighteen Panzer divisions still available to Hitler on the Eastern Front, a massive but necessary commitment. Dismantled factory equipment, cattle, and all things moveable were dragged away by the retreating German forces, now mainly interested in entrenching themselves along the western borders of Hungary, leaving it for Szálasi to win time for them. The Leader of the Nation announced total mobilisation, in principle extending to all men between the ages of fourteen and seventy. He rejected appeals from Hungarian ecclesiastical leaders to abandon Budapest after it had been surrounded by the Soviet forces by Christmas 1944. The senseless persistence of the Arrow-Cross and the Germans resulted in a siege of over one and a half months, with heavy bombardment and bitter street warfare, a ‘second Stalingrad’, as recalled in several German war memoirs. The long siege of Budapest and its fall, with an enormous loss of life, occupy an outstanding place in world military history. Only the sieges of Leningrad (St Petersburg), (Volgograd) and the Polish capital Warsaw, similarly reduced to rubble, are comparable to it.

‘Autumn Mist’ in the Ardennes:

Meanwhile, on the Western Front, Allied hopes that the war might be over in 1944, which had been surprisingly widespread earlier in the campaign, were comprehensively extinguished. By mid-November, Eisenhower’s forces found themselves fighting determined German counter-attacks in the Vosges, Moselle and the Scheldt and at Metz and Aachen. Hoping to cross the Rhine before the onset of winter, which in 1944/5 was abnormally cold, the American Allied commander-in-chief unleashed a massive assault on 16 November, supported by the heaviest aerial bombing of the whole war so far, with 2,807 planes dropping 10,097 bombs in ‘Operation Queen’. Even then, the US First and Ninth Armies managed to move forward only a few miles, up to but not across the Rühr river. Then, a month later, just before dawn on Saturday, 16 December 1944, Field Marshal von Rundstedt unleashed the greatest surprise attack of the war since Pearl Harbor. In Operation Herbstnebel (‘Autumn Mist’), seventeen divisions – five Panzer and twelve mechanized infantry – threw themselves forward in a desperate bid to reach first the River Meuse and then the Channel itself. Instead of soft autumnal mists, it was to be winter fog, snow, sleet and heavy rain that wrecked the Allies’ aerial observation, denying any advance warning of the attack. Similarly, Ultra was of little help in the early stages, since all German radio traffic had been strictly ‘verboten’ and orders were only passed to corps commanders by messenger a few days before the attack.

Suddenly, on 16 December, no fewer than three German Armies comprising 200,000 men spewed forth from the mountains and forests of the Ardennes. Generals Rundstedt and Model had opposed the operation as too ambitious for the Wehrmacht’s resources at that stage, but Hitler believed that he could split the Allied armies north and south of the Ardennes, protect the Rühr, recapture Antwerp, reach the Channel and, he hoped, re-create the victory of 1940, and all from the same starting point. Rundstedt later recalled that:

The morale of the troops taking part was astonishingly high at the start of the offensive. They really believed victory was possible. Unlike the higher commanders, who knew the facts.

The German disagreements over the Ardennes offensive were three-fold and more complex than Rundstedt and others made out after the war. Guderian, who was charged with opposing the Red Army’s coming winter offensive in the east, did not want any offensive in the west, but rather the reinforcement of the Eastern Front, including Hungary. Rundstedt, Model, Manteuffel and other generals in the west wanted a limited Ardennes offensive that knocked the Allies off balance and gave the Germans the chance to rationalize the Western Front and protect the Rühr. Meanwhile, Hitler wanted to throw the remainder of Germany’s reserves into a desperate attempt to capture Antwerp and destroy Eisenhower’s force in the west. As usual, Hitler took the most extreme and thus riskiest path, and as always he got his way. He managed to scrape up a reserve of twenty-five divisions, which he committed to the offensive in the Ardennes. General Model was given charge of the operation and planned it well: when the attack went in against the Americans it was a complete surprise. Eisenhower, for his part, had left the semi-mountainous, heavily wooded Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg relatively undermanned. He did this because he had been receiving reports from Bradley stating that a German attack was only a remote possibility and one from Montgomery on 15 December claiming that the enemy cannot stage major offensive operations. Even on 17 December, after the offensive had begun, Major-General Kenneth Strong, the Assistant Chief of Staff (Intelligence) at SHAEF, produced his Weekly Intelligence Summary No. 39 which offered the blithe assessment that:

The main result must be judged, not by the ground it gains, but by the number of Allied divisions it diverts from the vital sectors of the front.

For all the dédácle of 1940, the Ardennes seemed uninviting for armoured vehicles, and important engagements were being fought to the north and south. With Wehrmarcht movements restricted to night-time, and the Germans instituting elaborate deception plans, the element of surprise was complete. Although four captured German POWs spoke of a big pre-Christmas offensive, they were not believed by Allied intelligence. Only six American divisions of 83,000 men protected the sixty-mile line between Monschau in the north and Echternach in the south, most of them under Major-General Troy Middleton of VIII Corps. They comprised green units such as the 106th Infantry Division that had never seen combat before, and the 4th and 28th Infantry Divisions that had been badly mauled in recent fighting and were recuperating.

The attack took place through knee-high snow, with searchlights bouncing beams off the clouds to provide illumination for the troops. Thirty-two English-speaking German soldiers under the Austrian Colonel Otto Skorzeny were dressed in American uniforms in order to create confusion behind the lines. Two of the best German generals, Dietrich and Monteuffel led the attacks in the north and centre respectively, with the Seventh Army providing flank protection to the south. As the panzers raced for the Meuse and the Allies desperately searched for the troops they needed to rebuild their line, both armies wondered if Hitler had managed to bring off a stunning ‘blitz’ yet again. Yet even the seventeen divisions were not enough to dislodge the vast numbers of Allied troops who had landed in north-west Europe since D-day. The Allies had the men and Hitler didn’t. Manteuffel later complained of Hitler that:

He was incapable of realising that he no longer commanded the army which he had had in 1939 or 1940.

Nevertheless, both the US 106th and 28th Divisions were wrecked by the German attack, some units breaking and running to the rear, but the US V Corps in the north and 4th Division in the south managed to hold their positions, squeezing the German thrust into a forty-mile-wide and fifty-five-mile-deep protuberance in the Allied line whose shape on the map gave the engagement its name: the Battle of the Bulge. The Sixth SS Panzer Army failed to make much progress against the 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions of Gerow’s V Corps in the north and came close but never made it to a giant fuel dump near the town of Spa. They did, however, commit the war’s worst atrocity against American troops in the west when they machine-gunned eighty-six unarmed prisoners in a field near Malmédy, a day after executing sixteen others. The SS officer responsible, SS-General Wilhelm Mohnke, was never prosecuted for the crime, despite having also been involved in two other such massacres in cold blood earlier in the war.

In the centre, Manteuffel’s Fifth Panther Army surrounded the 106th Division in front of St Vith and forced its eight thousand men to surrender on 19 December, the largest capitulation of American troops since the Civil War. St Vith itself was defended by the 7th Armoured until 21 December, when it fell to Manteuffel. Although the Americans were thinly spread, and caught by surprise, isolated pockets of troops held out long enough to cause Herbstnehel to stumble, providing Eisenhower with enough time to organize a massive counter-attack. By midnight on the second day, sixty thousand men and eleven thousand vehicles were being sent as reinforcements. Over the following eight days, a further 180,000 men were moved to contain the threat. As the 12th Army Group had been split geographically to the north and south of ‘the bulge’, on 20 December Eisenhower gave Bradley’s US First and Ninth Armies to Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, the latter until the Rhine had been crossed. It was a sensible move that nonetheless created lasting resentment. German loudspeakers blared out the following taunt to troops of the US 310th Infantry Regiment:

How would you like to die for Christmas?

With Ultra starting to become available again after the assault, confirming the Meuse as the German target, the Supreme Commander could make his own dispositions accordingly, and prevent his front being split in two. Patton’s Third Army had the task of breaking through the German Seventh Army in the south. On 22 and 23 December, Patton had succeeded in turning his Army a full ninety degrees from driving eastwards towards the Saar to pushing northwards along a twenty-five-mile front over narrow, icy roads in mid-winter straight up the Bulge’s southern flank. Even Bradley had to admit in his memoirs that Patton’s ‘difficult manoeuvre’ had been one of the most brilliant performances by any commander on either side of World War II. Patton had told him, the Kraut’s stuck his head in a meat-grinder and this time I’ve got hold of the handle. Less brilliant was the laxity of Patton’s radio and telephone communications staff, which allowed Model to know of American intentions and objectives. But Patton seemed to think he had a direct line to God. In the chapel of the Fondation Pescatore in Luxembourg on 23 December, Patton prayed to the Almighty: